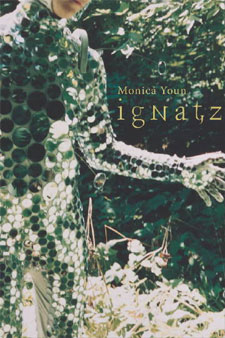

Monica Youn

Monica Youn

Ignatz

(Four Ways, 2010)

I picked up a copy of this after a performance at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop: word came from their email list that Matmos was going to be performing with Monica Youn. Matmos is one of the few electronic groups that’s reliably entertaining (see, for example, this clip on YouTube, as well as its weirdly civil comment thread), and as I’ve been going to Matmos shows on and off for the past ten years – having first run into them at the Festival Dissonanze in Rome, where they were contact-miking each other and making music out of that – I dutifully went along, knowing very little of Monica Youn, besides having seen her name about before. The company one keeps is important, of course; and I have been to enough poetry readings to know that interesting poetry readings are very much the exception rather than the rule. This was a nice one, in no small part because of how arbitrary it seemed: there’s nothing in Youn’s book that suggests that it needs to be remixed live to make sense, my problem with a lot of mixed-media poetics. (The blurbs on the back of the book – by Cal Bedient, Stephen Burt, and Matthea Harvey, all respectable enough – don’t suggest this either.) Rather the impression was that of listening to David Grubbs and Susan Howe reinterpreting her books live (the CD version of Thiefth and a live version of Souls of the Labadie Tract are now online at PennSound): it’s a different way into the words.

The performance was rather staid as Matmos performances go: a brick was hit with a rock hammer and looped to create a rhythm; drumsticks and, and one point, a rubber duck were thrown in as well. Previously sampled voices reading Youn’s poetry (probably the members of Matmos) mixed with Youn’s own voice. A synthesizer was in there somewhere as well. One had the sense of a sonic Rube Goldberg machine being constructed: the result wasn’t pop by any measure, but it had the playfulness of pop to it. Not knowing the book going into the performance, I don’t know how many poems formed part of the thirty-minute construction; one did have the sense of a character named Ignatz who recurred, and some sections did seem to be prose rather than verse. A particular standout was “Landscape with Ignatz,” a six line poem based on structured repetition, something like Queneau’s Cent mille milliards de poèmes:

The rawhide thighs of the canyon straddling the knobbled blue spine of the sky.

The bone-spurred heels of the canyon prodding the gaunt blue ribs of the sky.

The sunburnt mouth of the canyon biting the swollen blue tongue of the sky.

This does lend itself to an electronic rendition: taking the structure “The — — of the canyon —ing the — blue — of the sky” as a spine, different recorded voices and Youn’s live voice were substituted in for the parts. Not having the poem in front of me while listening, I don’t know how much of this was improvised or whether this was a straightforward performance of the poem.

Reading the book on the subway home, I found a similar sort of obliqueness: as most readers probably will, I started by reading the back cover’s paragraph-long blurbs, then made my way through the poems from the first page to the last. The blurbs inform you of the meaning of the title: Ignatz is a character in George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. I don’t know Krazy Kat, save from references: Wikipedia is helpful, but Wikipedia doesn’t exist on the subway. At the end of the book, we find an appendix with an explanation:

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip was published in U.S. newspapers from 1913 to 1944. The strip is set in Coconino County, Arizona, and stars Krazy Kat, a feline of indeterminate gender and mutable patois. Krazy is hopelessly in love with Ignatz Mouse, a rodent of criminal tendencies, who, in turn, despises Krazy and whose greatest pleasure is to bean the lovelorn cat in the head with a brick. Krazy interprets these missiles as tokens of reciprocated affection, and the cat-mouse-brick-love cycle recurs in almost every strip. Ignatz’s repeated assaults upon Krazy incur the righteous wrath of Officer Bull Pupp, the canine sheriff of Coconino County, who is sweet on Krazy and who takes every opportunity to spy out Ignatz’s crimes and to drag the recidivist mouse to jail.

Hence, of course, Matmos’s bricks (and perhaps an antecedent to their involvement can be found in their Rat Relocation Project); from this we can start to make sense of Youn’s poetry. From Youn’s description, one might think of Wile E. Coyote’s unfulfilled desire to catch the Road Runner; but that isn’t actually what the relationship between Krazy Kat and Ignatz is. Krazy wants Ignatz; Ignatz wants to throw bricks at Krazy; but a third member of the triad, Officer Pupp, keeps the law. One realizes that things aren’t quite as they seem from Youn’s notes, which point out what she’s borrowed from Herriman’s work: the epigraph from “The Subject Ignatz,” for example, is from Officer Pupp: “Once more an urge; once more a succumb.” This is the language of desire, but played out in the world: Pupp is describing what he sees, not what Krazy (whose position the speaker in most of these poem appears to take) feels. A handful of poems here (“Ignatz Incarcerated”) lay out words in rectangular matrices, looking at how structures can be used to relate them. In “X as a Function of Distance from Ignatz,” parenthetical phrases constantly intrude in the poem to relate the position of male and female figures.

And I like the language here: sources aside, this is a satisfying book. Later in “The Subject Ignatz,” we find “Asbestos / interlude: // the rubber / button // replumps itself,” cartoonish, but beautiful in the way the “u” sounds cascade through the stanza. Or “I-40 Ignatz”: “A cop car drowses / in the scrub // cottonwoods. Utmost. // Utmosted. There is / a happy land.” A note suggests that this poem “quotes Krazy”: these might be Herriman’s words rather than Youn’s, but they’re still worth noticing.

Pingback: Reviews: Ignatz (Stahlecker Selections) by Monica Youn | LibraryThing

The publisher is Four Way Books, not Four Walls.

You’re absolutely right – sorry for the slip-up!

Pingback: You've been Stumbled!