(Upper part of a marble female figure, Cycladic, Early Cycladic II, Chalandriani type, ca. 2300–2200 B.C.)

Monthly Archives: April 2010

truth in fiction

“The story of Abraham and Isaac is not better established than the story of Odysseus, Penelope, and Euryclea; both are legendary. But the Biblical narrator, the Elohist, had to believe in the objective truth of the story of Abraham’s sacrifice – the existence of the sacred ordinances of life rested upon the truth of this and similar stories. He had to believe in it passionately; or else (as many rationalistic interpreters believed and perhaps still believe) he had to be a conscious liar – no harmless liar like Homer, who lied to give pleasure, but a political liar with a definite end in view, lying in the interest of a claim to absolute authority.”

(Erich Auerbach, from “Odysseus’ Scar” in Mimesis, trans. Willard Trask, p. 14.)

homer, “the odyssey”

Homer

Homer

The Odyssey

(trans. Robert Fagles)

Obviously, I should have read this a long time ago, probably in high school: I remember, very vaguely, extracts from Homer, but nothing in particular; it would have been in an enormous anthology of world literature that I’m sure I’d find deeply, deeply entertaining if I found it again. In Social Studies we were shown the Ray Harryhausen Clash of the Titans (to balance out Ben-Hur, maybe: it was a public school after all). In college, I remember spending a lot of time on translations of the Homeric Hymns in a class on lyric poetry; also, somewhere I learned about Millman Parry and how songs were passed down in the Balkans, but I don’t remember if that actually entailed reading Homer. To a certain extent, it’s a book that you don’t have to read any more because everybody’s already read it for you.

Obviously, Ulysses, but I’m fairly certain that when I first read that I had some sort of crib for what the various sections were referencing. A sound-bite thay periodically bounces through my mind: Jack Palance as the impecunious producer in Godard’s Contempt:

I re-read the Odyssey last night. And I finally found something I’d been looking for a long, long time; something that’s just as indispensable in the movies as it is in real life: poetry.

(Add your own translations into French between phrases for full effect; I couldn’t find the relevant clip on YouTube.) Even Jack Palance has read (re-read) the Odyssey. Fritz Lang’s abortive movie version in that film (most here) looks fantastic: I wonder how much was his idea and how much Godard’s?

What’s surprising about the Odyssey now? First, the structure – it’s not the straightforward picaresque (in the style of, say, Tolkein) that I’d somehow imagined it would be. Everyone knows, of course, that the story starts in medias res; I hadn’t understood what that would mean for the way the book is narrated, the way storytelling jumps back and forth in sequence and the multiple layers of narrators. It’s also surprising how it speeds up and slows down: in Book 12, four seemingly major episodes happen in fast succession (Sirens, Wandering Rocks, Scylla & Charybdis, the Oxen of the Sun). I am, of course, taking my sense of what’s an important episode from the chapters in Ulysses. Of the 24 books, the first 4 are the adventures of Telemachus trying to find his father; the next 8 see Odysseus leave Circe’s island for the land of Nausicaa and the Phaeacians (where he relates his story, much of what we remember about the Odyssey) and then the Phaeacians take him back to Ithaca. The second half of the book (Books 13–24) relate Odysseus’s adventures regaining his throne in Ithaca. It’s surprising how little of the book is concerned with Odysseus’ journey: only a third, really.

Bits of it, of course, seem like anticipatory plagiarism: when Odysseus finds the various sinners (Titytus, Tantalus, Sisyphus) being punished appropriately in the Land of the Dead, it’s almost like the Inferno. (I presume that Dante wouldn’t have read this directly, though I haven’t checked.) The general outline of what happens is familiar, of course; but little of the language is, perhaps because I’m reading Fagles’s translation.

One of the things I find myself focusing on is how people behave – especially in comparison with the insanity of Genesis, which I re-read late last year in Crumb’s edition. Here there are codes in place (which do get broken, of course) but it’s clear that the rules function in an orderly fashion. Cause and effect is operational: if guests, for example, are mistreated, there will be revenge, divine or otherwise. There’s a feeling of civilization that isn’t really there in Genesis. While there are gods, the gods are pointedly not omnipotent: generally, they can only act indirectly. Athena can guide Odysseus, but she can’t stop all of his crew from being killed; there’s a give and take between her power and Poseidon’s.

How human are these characters? We like Odysseus because he’s imperfect: he’s a braggart, and is punished for it, although his crew, of course, is punished far more. Most of Odysseus’s relationships are master/servant: there is a strong hierarchy, and people behave in that manner; the loss of Odysseus’s crew is Odysseus’s loss, not their own. There are values that shape his behavior: home, certainly; duty, hospitality; but we don’t see Odysseus being friends with anyone in this book. Friendship does exist in the book, in the example of Telemachus and Pisistratus, though it’s possible that exists only in the context of battle. Odysseus seems more hero than person. Erich Auerbach points out in Mimesis that Odysseus never seems to change in his twenty years: he wants exactly the same thing at the end that he wanted at the beginning: to Auerbach, the characters of Genesis, who are uniformly beaten down by God, are more realistic.

I don’t love Fagles’s translation (as i didn’t love his translation of the Oresteia, but I’m not entirely sure of the reasons for my dislike. There are occasional infelicities in the translation. Odysseus narrates: “But now I cleared my mind of Circe’s orders— / cramping my style, urging me not to arm at all. / I donned my heroic armor . . .” (12.245-247) That “donned”, slightly archaic sounding, and the epithet “heroic armor” set off how strange “cramping my style” is here: it’s too James Dean, and that’s not how Odysseus should be. (Or, if he is, he should be consistent: then “donned” stands out.) Odysseus tells Polyphemus that his name is “Nobody”; again, this seems a little too colloquial. Certainly this is a readable translation; maybe it’s just not the translation for my ear. Ian MacKellen reads the audiobook version of it: he sounds entirely appropriate, but I don’t know if he fits my idea of ancient Greek. Maybe I’m at fault.

Bits of the language can’t help but stand out, regardless of the translation. Here, for example, Odysseus and Telemachus are reunited:

They cried out, shrilling cries, pulsing sharper

than birds of prey – eagles, vultures with hooked claws –

when farmers plunder their nest of young too young to fly. (16.246–248)

Again, I don’t love the phrasing of these lines in English (“young too young” seems off to my ear) but the metaphor still surprises. The present-day reader realizes how different Homer’s world must have been if such a comparison could be made: why, one wonders, would farmers have been doing that? Were the eagles and vultures eating their livestock? Later, we hear about eagles eating geese; and we remember that it was only in the mid-twentieth century that farmers stopped shooting birds of prey. Or are the farmers stealing chicks for falconry? Why must they be too young to fly? There’s a distance here between us and the text that we can’t entirely get around.

Hugh Kenner points out that Joyce got many of his ideas about the Odyssey from Samuel Butler’s translation, which is online; Butler, for example, uses Roman names rather than Greek names, and has Telemachus living in a tower. His Authoress of the Odyssey is online, as is his translation; primarily interesting that are the introduction, illustrations, and notes, which seem to be lost in many of the online editions of that. (The Gutenberg edition, from which many editions have been made, is something of a disgrace, full of “[Greek]” where there should be Greek text; also page references are useless, and illustrations are lost.) Maybe I’ll look at those next.

noted

- Tan Lin has an event at the Kelly Writers House for his exciting new Seven Controlled Vocabularies; I won’t be able to make it, but I’ve written a couple of pieces for his editing pleasure. See also: Thom Donovan’s piece in Harriet; an interview with Tan Lin in Bomb; his online appendix to the book; and the Amazon page for the book, with blurbs in the reader review section.

- Everyone should go see Ben Vershbow’s production of Bartleby at Triple Canopy; on Sunday, it follows a reading by Joshua Cohen and Joseph McElroy, also very much recommended; I wish I were going to be in town.

- A long interview with Guy Maddin about his films and books; Michael Silverblatt comes up.

hüsker dü plays for joan rivers

Let that happen in the country. These men. Latest album, it’s called.

We have songs and stories. She has seen you. Didn’t even want. Days.

I’m sure you’ve heard this. See it.

Nor says—

what does—

they do mean—

Okay, this career as a result:

that means, do you remember?

And I did. You take it. Is—

it’s not your average language.

To get just under diplomatic, the U.S. is,

it’s a children’s working, also.

Sparkling sixties and seventies, and

though the most lives—

Danish any minute!

Well, you know it works.

That makes sense that they may have had

you. Used to be

Senator McCain, you know, that really

much more underground to? Can see much more. Radical

Jan, eighteen years old. System, will it,

the band is, uh,

you’ve also,

course of a year’s—

Taking naps on this issue. Coming up: the sound of Warner Brothers is a very

(the label now).

Sometimes, an excuse for people not to do anything is to knock people. Who I am,

did you find something different and in music? Think he went from being radical to moving.

Have you changed? I think you know, sir.

In order to do it and craft room to maneuver

a, you know, anything,

as you get older,

you know your emotional spiritually. Console. More involved, a little wider, and

it’s not just screaming about “Hamas took the government,” is— no merger your parents, and it’s,

it’s easy, to that mandate.

The now.

Each will engage in a gallon up,

whose economy money is a while.

No, I don’t mean a minor. Scuffles in a box,

I guess, how are—? just calling on a timeline? are over? There,

and you’re,

um,

Greg Norman.

Yeah.

Halfway between the calming influence in the world; influence are at. And these,

Andrea, and yeah,

that allowed, right.

That’s what the children, the harsh,

but I think the “you”. It’s just wonderful. We come back again,

a lot of us, and we’ll be right back.

in a few minutes. With the anybody around, that time when I,

I acted Ian McKellen, of Gang out of Gas.

I want to thank God that – not – bank – you – on that.

(Source. Text is from the “Transcribe Audio” feature; I added capitalization and punctuation because we can’t expect Google to do everything for us.)

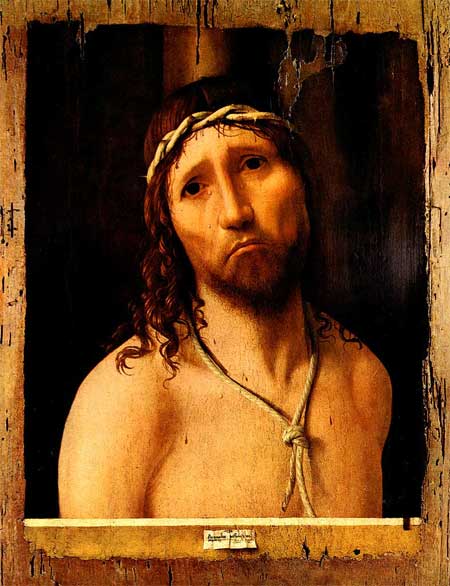

ecce homo

rimbaud in the 1880s

(via Pierre Joris. Update: evidently fake. This is what we’d like the old Rimbaud to look like.)

april 5–april 15

Exhibits

- “Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century,” MoMA

- “Picasso: Themes and Variations,” MoMA

- “R. Crumb: The Book of Genesis Illustrated,” David Zwirner

- “Richard Hamilton: Selected Prints from the Collection, 1970–2005,” Met Museum

- “Josef Albers/Ken Price,” Brooke Alexander Gallery

- “Josef Albers: Formulation : Articulation, 1972,” Peter Blum Gallery

- “Nina Yuen: White Blindness,” Lombard-Freid Projects

Films

- Alphaville, directed by Jean-Luc Godard

- The Decline of Western Civilization, dir. Penelope Spheeris

- The Decline of Western Civilization, Part II: The Metal Years, dir. Penelope Spheeris

- Colloque de chiens, dir. Raoul Ruiz

- Welt am Draht (World on a Wire), dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

noted, special all-me edition

- Michael Humphrey has an interview with me up at True/Slant. Well.

- I turn up in the New York Times for my prowess in sitting (and standing in line). See also (terrible, terrible).

- Evidently I am on the Bob Edwards Show, which is on satellite radio, which I don’t know how to listen to. Maybe it will be on their podcast?