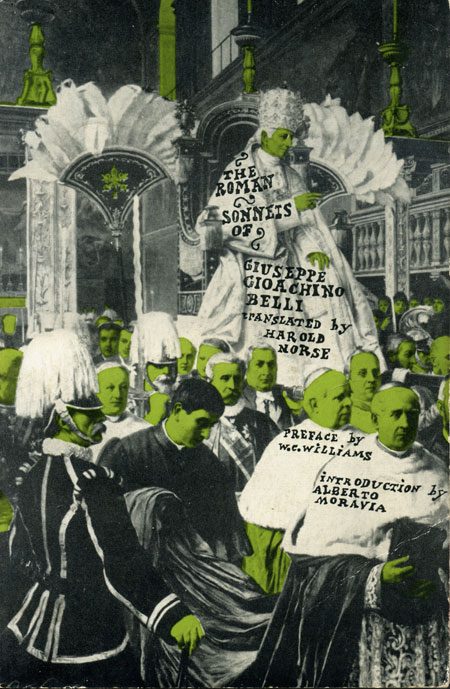

(The Roman Sonnets of Giuseppe Gioachino Belli, translated by Harold Norse, preface by William Carlos Williams, introduction by Alberto Moravia. Published by Jonathan Williams, 1960; cover by Ray Johnson.)

Tag Archives: ray johnson

ray johnson & bill wilson, “a book about a book about death” / “from bmc to nyc: the tutelary years of ray johnson 1943–1967”

Ray Johnson & Bill Wilson

Ray Johnson & Bill Wilson

A Book about A Book about Death

(Kunstverein Publishing, 2010)

From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson 1943–1967

curated by Sebastian Matthews

(Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, 2010)

These are two catalogues of recent shows of the work of Ray Johnson. Johnson was a visual artist; but it’s his use of language, in its different incarnations, that keeps me interested in his work. Johnson could profitably be read as a poet; to my knowledge, this hasn’t really happened.

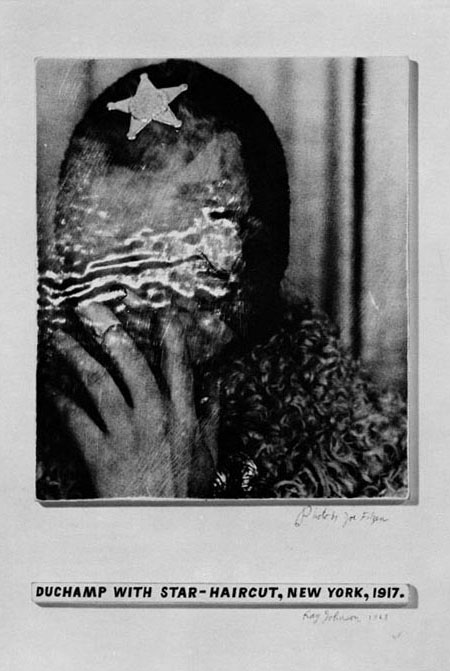

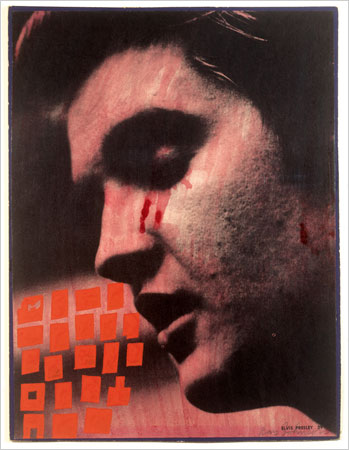

The first of these catalogues accompanied a show at the Black Mountain College Museum; it focuses on Johnson’s work when he was attending that school (then being run by Josef Albers) and work done during his early years in New York, though it draws back even further, presenting a series of illustrated letters and cards that Johnson sent to a high school friend, Arthur Secunda, in the early 1940s. In all of these, there’s a mixing of text and image: sometimes illustrations added to text, sometimes text built around illustrations, and, more rarely, collage, the principle that much of Johnson’s later work would spring from. It’s unclear whether Johnson thought of this as “mail art,” though it certainly could be described as that; he did declare that he thought his work should be catalogued back to 1943, which might make that case. Despite this, Not a huge amount of Johnson’s early work, especially what he was doing at BMC, survives: he cut up most of it to serve as content for later works in the form of tesserae, and he evidently burned his class notes in the 1950s. Julie J. Thomson’s essay scrutinizes the effect of the teaching of Albers on Johnson: in particular, she points to his assimilation of Albers’s ideas on colors, which resonate through his later work. His famous portrait of Elvis Presley as Oedipus, for example, might be seen as a meditation on the meaning of red, that collage’s dominant color: red streaming from the eyes signifies blood, but were the image in black and white, as the original image of Presley is, the streams might as easily be tears. In front of Presley’s mouth appear blocks of red, rectangular but of irregular proportions, seemingly representing words: the shapes are abstract like language, and though each is of the same color red, the meaning of a word varies with context, just as the value of red varies in the color studies of Albers.

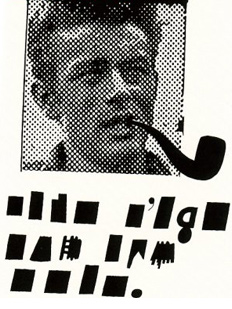

Kate Erin Dempsey’s essay looks at how Johnson used language: in particular, the influence of Mayan hieroglyphs, a frequent subject of scrutiny at BMC. The hieroglyphs had not yet been discovered, but it was clear that this graphical system signified: the form of a glyph has several layers of meaning, only some of which were available. This fascination with the visible form of language continues in Johnson’s later work: an work from the 1980s owned by the LACMA is given the title Untitled (James Dean with Magritte’s Pipe):

The apostrophe is a clue for the informed viewer what the rectangles stand for: Magritte’s ceci n’est pas une pipe, though actually fitting those letters into the rectangles proves challenging: the text both belongs there and it doesn’t belong there. The image is both Dean but also – and very clearly – the Ben-Day dots that make up his image. The pipe is a silhouette of Magritte’s. Dempsey points to earlier work employing the same strategies:

Several collages contain definitions cut out of a Yiddish dictionary. Others include Chinese characters with their English translations below. In Untitled (Toad/Water) of 1957, for example, a picture of a toad is followed by the Chinese symbol for toad, “Toad,” and then the Chinese symbol for water and finally “Water.” It could very easily also have text explaining, à la Magritte, “This is not a toad,” for neither the image, the Chinese symbol, nor the English word really ARE the signified. (p. 25)

It’s hard to tell from the reproduction if the image above the words is actually a toad (there might be bumps on its back) or a frog (as the coloring of the legs seems to suggest); while I’ve seen the original, I don’t remember whether it actually was a frog or a toad.

The BMC book concludes with an essay by William Wilson, owner of the toad collage, ruminating on the meaning of hats – and specifically Marianne Moore’s tricorner hat – as they cascaded through Ray Johnson’s work:

Those hats for women in society, perhaps worn for lunch at Schrafft’s, were a visual answer to the question, What do women want? The hats provided an answer for husbands: women want too much, and want more than is good for them, hence they must be governed by men for their own protection. The men judged themselves as reasonable and functional, indulgently governed the women whom the men assigned themselves to protect. The plot of many movies from the 1930s is telegraphed ahead in the hats the male and female characters are wearing. Katherine Hepburn did not wear fanciful hats. Watch for the moment a wife removes her dizzy hat, takes off her white gloves, and turns toward the husband, who feels he knows better than she does what she needs.

Moore’s tricorn Napoleonic hat was androgynous, with a military air, suggesting an image that had survived historical forces, and picturing and imagination capable of military strategy and reason. Her hat was, and is, an image of her imagination as she kept it persistently answerable to experience. She praised New York (Manhattan) for its “accessibility to experience.” And she aspired to an art of poetry as an imaginary garden with real toads in it. Marvelously, she mentioned that she wore her tricorn hat because her head was shaped like a hop toad. A toad is an image of experience without false illusions, like the toad before it is enchanted into a prince, who must become like a poet, a self-governing governor of images and themes. Moore used the hat to meditate on her modesty, to challenge herself, for while she wore it as armor for her soul, the hat revealed her imagination and her aspirations, so that she could not lie to herself about her modesty, and always had to review her renunciations. (p. 28)

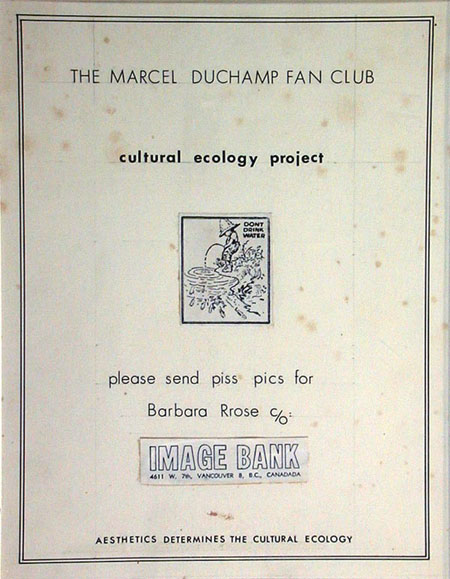

Wilson was a long-time friend of Johnson, and the executor of his estate after his death; his earlier With Ray: The Art of Friendship (published as part of the Black Mountain College Dossiers series) is the best introduction to Johnson’s work available; a complete set of his essays would be an invaluable book. A Book about A Book about Death is an extended essay about Johnson’s A Book about Death. From 1963 to 1965, Johnson mailed 13 pages of his Book to a handful of correspondents (including several members of Wilson’s family); the pages weren’t sent all together, and most recipients didn’t all the pages. The book-ness of such a work comes into question; so it was also referred to as a “boop” or a “boom”.

Wilson works through each page of A Book about Death, which is very much about death. The first page, for example, contains an ouroborous; the text “Mary Crehan, 4, choked to death on a peanut butter sandwich last night” (handwritten, though presumably found in a newspaper); an accidental splotch of ink next to the author’s name. Wilson’s analysis of how this page is worth reading in its entirety and doesn’t lend itself to excerption; after a discussion of chance in the making of art, an enormous subject for American art in the 1950s and 1960s, we get this:

The accident of a drop of ink is part of the comedy of constructing a work of art, a process which can’t say much about how it works. However, the comedy of chance is answerable to tragedy, because some accidents cause something good to perish. The effect is that “chance” renders the accident unknowable in its causes, and unintelligible in a universe presided over by a God who is good. The child choking to death is a large irreversible accident, and such perishing is a tragedy such as art is answerable to. That Mary Crehan choked to death on a peanut butter sandwich is absurd, so that it joins the absurdities which raise questions of consolations for the death of a child four years old. The cartoonish image of a rabbit at the bottom of the page is not adequate as explanation or consolation. The rabbit is Ray Johnson, representing the rest of us, who understand no more than a rabbit does of where we have come from, where we are, and where we are going. Ray was aware that Anne and Bill Wilson had had a daughter who had died shortly after her birth. (pp. 15–6.)

Wilson is not a disinterested reader; but this is not a disinterested text; as mentioned, this was a book created as correspondence, sent to specific readers, some of whom were mentioned directly in the text. This is not a book in the simplistic sense that we usually have of how an author and readership works: this is a book that was designed for specific readers. Wilson’s reading of the book is something of a gift: it opens Johnson’s thinking to the potential readers who did not know him. Johnson is of course dead: he can no longer explain his work directly.

So many causes may have contributed to the incompleteness of the Boop about Death that no one cause can be isolated. Without an explicit cause, no one is either responsible for this book, not to be credited with this book. Thus the question is about what we have here, an unbound book which no one was supposed to have a complete version of. For Ray, The Book about Death must remain an open work, lest an event of dying close a book on life. A closed book is death, or is an image of death, while The Book about Death is an open book. One theme of this unfinished Boom about Death is that death does not close, death opens. (p. 55)

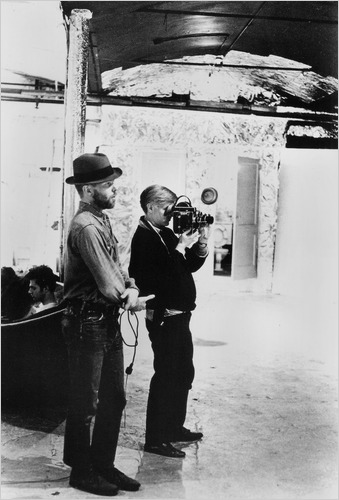

ray johnson & andy warhol

(Ray Johnson, left, and Andy Warhol in a photograph by Billy Name. Illustration from “In Search of an Archive of Warhol’s Era,” NYTimes, 9 January 2010.)

a part of a collage

“When I write about Ray [Johnson]’s art in relation to his life, at least two massive problems emerge:

1) To look at a part of a collage and trace it to its past causes the wholeness of the collage to disintegrate, and each portion to lose that part of its meaning which is its bearing upon the other parts as Ray arranged them. One can have the work of art, or one can have its sources. In tracing the work to its sources it is lost, because as analysis disintegrates the whole into parts, the parts lose their meaning, which is the bearing of part upon part in the construction of a unified work of art.

2) To look at a part of a work of art by Ray Johnson, and to follow from it toward his drowning, is to subsume the work in a larger whole, a final act of his life. But the images in the collages are hypothetical, and the work of art is more than just material or physical. It exists as it is perceived at a certain focal plane, and its wholeness is an aesthetic illusion, available to none of the sciences, and probably to no animal but humans. But Ray’s drowning is not hypothetical, it is categorical. While as an event it gathers many images which Ray has used in his art, and which he has acted upon in his life – hanging out around water – it is not a work of art or an aesthetic illusion, and it is not hypothetical.”

(William S. Wilson, With Ray: The Art of Friendship, p. 30.)

poem for ray johnson

Camels in the snow.

Frankfurt

December, 1962

(Dick Higgins, Jefferson’s Birthday/Postface, p. 99 of Jefferson’s Birthday.)

variously/joseph kosuth

- Jenny Diski has a blog.

- There’s a new Ray Johnson show at Richard Feigen. Focuses on “a significant body of Johnson’s collages that reference other artists, his peers and his friends.” Preview tonight from 6–8. Info here.

- Jenny Kronovet hosts a reading for poets from Crowd (Mary Jo Bang, Eric Baus, and Matthew Rohrer) at the Marquise Dance Hall in Williamsburg. Sunday 12 November at 7 pm.

- And there are poems by Stefania Heim online at Harp and Altar. Also: some criticism.

Also: a bunch of illicit photographs from the recent Joseph Kosuth installation at Sean Kelly:

ray johnson, rudy burkhardt & peter hujar at vassar

Reviewed by Holland Cotter at the NY Times.

variously

- An effort to put Finnegans Wake into a wiki full of annotations.

- Ron Silliman goes to DC & thinks about aura w/r/t Sandra Day O’Connor and the Air & Space Museum.

- And there’s an opening at Pavel Zoubok tomorrow night for a show of Ray Johnson, May Wilson, Al Hansen, Buster Cleveland, and John Evans, but their website is not so up-to-date. Hopefully they are busy doing other things. Some information here, for the moment. More Al Hansen on show at Andrea Rosen.

- Coming up: an Eva Hesse show at the Drawing Center.