Monthly Archives: April 2006

effingham

“Max smiled. He said, ‘I shall take refuge in the Phaedrus. You remember at the end Socrates tells Phaedrus that words can’t be removed from place to place and retain their meaning. Truth is communicated from a particular speaker to a particular listener.’

‘I stand rebuked! I recall that passage. But it is a reference to mystery religions, isn’t it?’

‘Not necessarily. It can apply to any occasion of learning the truth.’

‘Do you think Hannah – desires the true good?’

Max said after a long silence during which Effingham found himself nodding with sleep, ‘I’m not sure. And I don’t think you can tell me. It may all be to meet some need of my own. I’ve meant all my life to go on a spiritual pilgrimage. And here I am at the end – and I haven’t even set out.’ He spoke with a sudden fierceness, cutting and lighting a cigar with quick precision and moving the ash-tray farther down the table with a loud clack. He added, ‘Perhaps Hannah is my experiment! I’ve always had a great theoretical knowledge of morals, but practically speaking I’ve never done a hand’s turn. That’s why my reference to the Phaedrus was damned dishonest. I don’t know the truth either. I just know about it.’ ”

(Iris Murdoch, The Unicorn (1963), pp. 100–101.)

(Frank Stella, Effingham I (1967), in the Van Abbemuseum.)

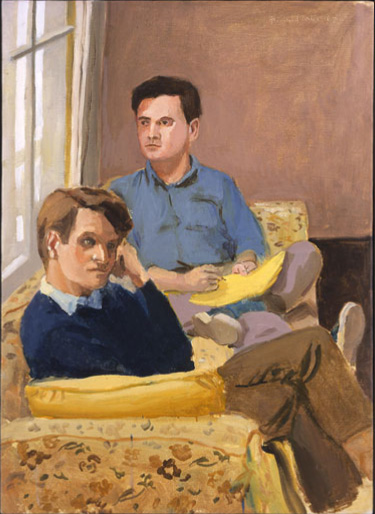

porter/ashbery/schuyler

Fairfield Porter, John Ashbery and James Schuyler Writing “Nest of Ninnies”, 1967. Oil on canvas; 36″ x 26″. On show at the Betty Cunningham Gallery’s Fairfield Porter: Painting and Works on Paper which closes today.

(Review at the Brooklyn Rail.)

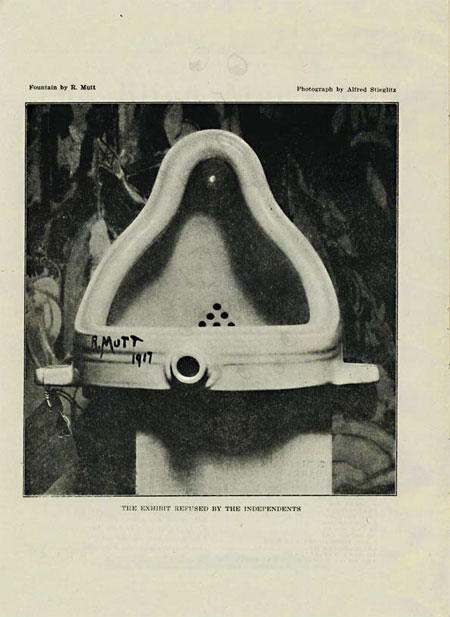

marsden hartley/fountain

I wish I could find a better image online of Marsden Hartley’s 1913 painting The Warriors:

It’s the background in Alfred Steiglitz’s photograph of Duchamp’s Fountain in The Blind Man:

It’s odd that the backdrop to such a well-known photo seems to have so little existence online.

(There’s a slightly larger version in this essay by Marjorie Perloff, but that’s in black and white. She does note how similar the urinal looks to Hartley’s painting.)

(Related: Ron Silliman goes to see the Dada show in D.C. and is somewhat disappointed. He does catch what’s wrong with the show there.)

from the encyclopædia acephalica

“WORK. — ‘I have no idea what the meaning of work is in our epoch, but I believe virtuosity is an infirmity, knowledge a dangerous asset, and I am well content to have some genius and no talent, which allows me not to work, and to play like a child: Work is an ostentatious thing, ugly and bogus as Justice.’ — K. Van Dongen”

(entry in the Encyclopædia Acephalica by Georges Bataille etc., p. 84 in the translation by Iain White.)

paper machine

“One evening I was walking along Hollywood Boulevard, nothing much to do. I stopped and looked in the window of a stationery shop. A mechanized pen was suspended in space in such a way that, as a mechanized roll of paper passed by it, the pen went through the motions of the same penmanship exercises I had learned as a child in the third grade. Centrally placed in the window was an advertisement explaining the mechanical reasons for the perfection of the operation of the suspended mechanical pen.

I was fascinated, for everything was going wrong. The pen was tearing the paper to shreds and splattering ink all over the window and on the advertisement, which, nevertheless, remained legible.”

(John Cage, from “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run” in A Year from Monday, p. 134. Interestingly online here.)

duchamp/roussel

“Roussel was another great enthusiasm of mine in the early days. The reason I admired him was because he produced something I had never seen. That is the only thing that brings admiration from my innermost being – something completely independent – nothing to do with the great names or influences. Apollinaire first showed Roussel’s work to me. It was poetry. Roussel thought he was a philologist, a philosopher and metaphysician. But he remains a great poet.

It was fundamentally Roussel who was responsible for my glass, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. From his Impressions d’Afrique I got the general approach. This play of his which I saw with Apollinaire helped me greatly on one side of my expression. I saw at once I could use Roussel as an influence. I felt that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter. And Roussel showed me the way.

My ideal library would have contained all Roussel’s writings – Brisset, perhaps Lautréamont and Mallarmé. Mallarmé was a great figure. This is the direction in which art should turn: to an intellectual expression, rather than to an animal expression. I am sick of the expression ‘bête comme up peintre’ – stupid as a painter.”

(Duchamp, interviewed by James Johnson Sweeney, 1946)

grammars of color

“Find the papers about colors considered in the sense of coloring light sources and not differentiations within a uniform light (sunlight, artificial light, etc.)

Come back to:

Supposing several colors – light-sources – (of that order) expose at the same time, the optical relationship of these different coloring sources is no longer of the same order as a comparison of a red spot with a blue spot in sunlight. There is a certain inopticity, a certain cold consideration, these colorings affecting only imaginary eyes in this exposure. (The colors about which one speaks. A little like the passage of a present participle to a past one.”

“I mean the difference between speaking about red and looking at red. [M.D., 1965.]”

(Duchamp, note in Á l’Infinitif (The White Box) (published 1967), trans. Cleve Gray.)

a private language

“Take a Larousse dict. and copy all the so-called “abstract” words. i.e., those which have no concrete reference.

Compose a schematic sign designating each of these words. (this sign can be composed with the standard stops.)

These signs must be thought of as the letters of the new alphabet.

A grouping of several signs will determine

(utilize colors – in order to differentiate what would correspond in this [literature] to the substantive, verb, adverb declensions, conjugations etc.)

Necessity for ideal continuity. i.e.: each grouping will be connected with the other groupings by a strict meaning (a sort of grammar, no longer requiring a pedagogical sentence construction. But, apart from the differences of languages, and the “figures of speech” peculiar to each language – weighs and measures some abstractions of substantives, of negatives, of relations of subject to verb, etc, by means of standard signs. (representing these new relations: conjugations, declensions, plural and singular, adjectivation inexpressible by the concrete alphabetic forms of languages living now and to come.).

This alphabet very probably is only suitable for the description of this picture.”

(Duchamp, note from The Green Box (published 1934), trans. George Heard Hamilton.)

(john cage’s “ryoanji” on the ipod)

“. . . And all the while, accompanying my every step, The Photographer is sounding in my head, purling incessantly through my clamped-on Walkman; it’s a good piece, Glass’s homage to Muybridge, minimalism used to maximal effect: with its repeating rhythms, endlessly rechurning, the music resembles a wave that doesn’t move, a standing wave; that’s what you listen to, the change and unchange of the wave, not any emergent melody: listening not above, but within; nowadays, I sit in Meador Park for hours on end plumbing the piece, turning the cassette over and over to extend it indefinitely; and it goes, the music just goes, without faltering, without hesitation, not depleted through repetition, but enriched; and as it goes – without faltering, without hesitation – the rapid-rushing piece instantly becomes the soundtrack to what I am looking at, regardless of what it may be: the varied tilts of oldsters’ hats, wind-gusts corduroying the park’s grass, the sparkling of pram wheels, children stepping onto the water fountain’s access ledge and hunchbacking behind their button-pushing hand and jutting lips; the music suits it all perfectly, uncannily, as absolutely apt accompaniment, the spirit of vision converted into onflowing sound; further it works just as well in the other direction: whatever I see also functions as a perfect illustration of The Photographer’s ceaseless undulant nattering; every event and gesture in my visual field – bicycle-spokes fanning, pinkie balls trickling across the ruffling green – seems to spring from some hidden imperatives of this unheard music: sight and sound have adhesive properties of which I had never before dreamed . . .

. . . It’s a question, really of figure and ground, of learning to integrate the two: of linking the landscape to the flamelike cypress thrusting up within it, of considering the World along with Cristina: dissolving patterns into particles . . . ; and I, for one, am perfectly positioned to make such investigations: I am either a bland assemblage of denim, sweatcloth, sneaks, connecting flesh and Walkman scudding through the streets of Springfield, barely perceptible in its random passages, or an indrawn 19-year-old with slightly stooped posture who has run away; it depends on whom you ask for the description: me, or anyone else in the world but me; figure and ground; figure or ground; but who, since Muybridge, even looks at the ground?; and Cristina was a cripple—”

(Evan Dara, The Lost Scrapbook (1995), pp.8–9)