(Previously.)

First:

Also:

Although:

(Previously.)

First:

Also:

Although:

“Unity of plot does not, as some persons think, consist in the unity of the hero. For infinitely various are the incidents in one man’s life which cannot be reduced to unity; and so, too, there are many actions of one man out of which we cannot make one action. Hence the error, as it appears, of all poets who have composed a Heracleid, a Theseid, or other poems of the kind. They imagine that as Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must also be a unity. But Homer, as in all else he is of surpassing merit, here too – whether from art or natural genius – seems to have happily discerned the truth. In composing the Odyssey he did not include all the adventures of Odysseus – such as his wound on Parnassus, or his feigned madness at the mustering of the host – incidents between which there was no necessary or probable connection: but he made the Odyssey, and likewise the Iliad, to center round an action that in our sense of the word is one. As therefore, in the other imitative arts, the imitation is one when the object imitated is one, so the plot, being an imitation of an action, must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that, if any one of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed. For a thing whose presence or absence makes no visible difference, is not an organic part of the whole.”

(Aristotle, Poetics, section VIII, trans. S. H. Butcher)

“It all begins with the stately splendour of the swelling counterpoint. The frontline is still sufficiently clear in the expanded portion of the stroke, but the contrast relies on its contraposition with a thin stroke in which the frontline spins about on an imploded counterpoint. When even contrast is renounced as superfluous ornament, writing is altogether without orientation. Now the barbarians can have their say with their plans to improve the alphabet so it will be easier for children, computers and other illiterates. Whatever they say is completely true in advance because the criterion is annihilated: a line can be drawn in any direction through a point, just as an echo chamber confirms any piece of nonsense.”

(Geerit Noordzij, The Stroke: theory of writing, trans. Peter Enneson, p. 70)

(Painting by Mauro Reggio, Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, from the website of Arte Antica Salamon Gallery. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a painting of this building before, which is somehow surprising.)

“A nation that swears by the Bible also finds it an incomparable book of reference. Alas, the explicitness of the Scriptures in matters of architecture is never as disconcerting as when we learn (Genesis IV: 17) that Adam’s son Cain built a city and named it after his son Enoch. A one-family town, delightful as it sounds, is a most extravagant venture and surely was never repeated in the course of history. If it proves anything, it illustrates the breathtaking progress made within a single generation, from the blessed hummingbird existence in well-supplied Paradise to the exasperatingly complicated organism that is a town. Skeptics who dismiss Enoch as a chimera will find more significance in the Ark, particularly in view of the fact that it was commissioned by the Lord Himself and built to His specifications. The question of whether the Ark out to be called a building or a nautical craft is redundant. The Ark had no keel, the keel being an intellectual invention of later days, and we may safely assume that ships were not known as yet, since their existence would have defeated the very purpose of the Flood. When Noah landed on Mount Ararat he was 601 years old, a man past his prime. He preferred to devote the rest of his life to viniculture and left the task of building to his sons. The Bible mentions (Genesis IX: 27) Shem’s huts – probably put together with some of the Ark’s lumber – but the decline in architecture was sealed.”

(Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects: a short introduction to non-pedigreed architecture, non-paginated, from the preface.)

“This concept developed out of Maciunas’ discussions with George Brecht and what Maciunas refers to in several letters as a “Soviet Encyclopedia.” Sometime in the fall of 1962, Brecht wrote to Maciunas about the general plans for the “complete works” series and about his own ideas for projects. In this letter Brecht mentions that he was “interested in assembling an ‘endless’ book, which consists mainly of a set of cards which are added to from time to time . . . [and] has extensions outside itself so that its beginning and end are indeterminate.”59 This idea for a expandable box is later mentioned by Maciunas as being related to “that of Soviet encyclopedia – which means not a static box or encyclopedia but a constantly renewable – dynamic box.”60 The exact origin of this idea of an expandable publication, though, is not as important as the fact that it is another indication of the general development of Fluxus publications away from more traditional notions of art publications.”

59. George Brecht, letter to George Maciunas, nd [ca. Nov./Dec. 1962], p.2. AS. Although the date on this letter is not certain, it was sent after Newsletter No. 4 and prior to the middle of December when Maciunas responded to it.

60. George Maciunas, letter to Nam June Paik, nd [after Jan. 15, 1962], AS.

(Owen Smith, Fluxus: the history of an attitude, p.88 and notes)

Both almost invisible on the Internet:

Walking home from work on Friday night, I came across this giant catfish. It was outside of a little Bangladeshi shop on 73rd Street. As you can see from one of these (very bad) photographs, it weighted 184 pounds; it was probably about five feet long. I asked where it was from and was told it was from Pakistan – evidently flying frozen fish from Pakistan to New York is a very ordinary thing, which astounded me – you would think there would be an easier way to get fish. They wanted $800 for it, so I didn’t buy it.

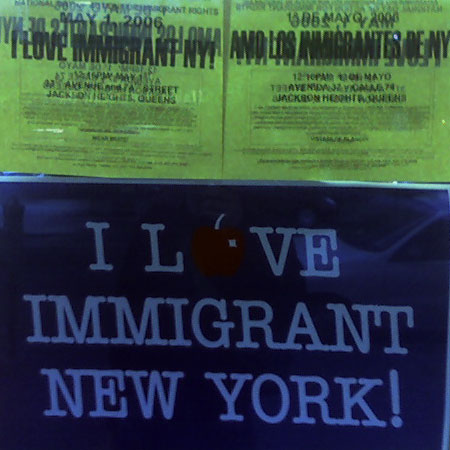

Belatedly, a shirt for wearing to immigration protests:

Also, one can’t help but note that the Spanish slogan for the marches is much better than the English one (squint to see it in the picture): in English, one is asked to love the abstract “Immigrant NY” while in Spanish we love the more concrete immigrants of New York: