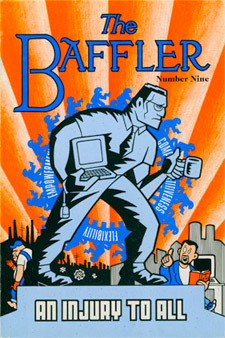

The Baffler #9: An Injury to All

The Baffler #9: An Injury to All

ed. Thomas Frank

Still working my way through old Bafflers: this one’s from 1997. I might be reaching my saturation point: this one took me a while to get through, in no small part because of what the editorial note describes as this issue’s “particularly unhappy tone”. This issue is unusually focused; most articles are on the sorry state of the labor movement in this country in the mid-1990s. Chris Lehmann looks at labor in the academy; Peter Rachleff looks at strikes against Hormel in Minnesota; David Moberg looks at attempts at organizing hotel workers in Los Angeles; Bob Fitch inspects the current state of the AFL/CIO. There’s some history as well: Frances Reed looks back at textile worker strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts; Hunter Kennedy looks at the forgotten history of cotton strikes in Mississippi; an illustrated piece by Jessica Abel looks at the legacy of labor unrest in Decatur, Illinois, and Jim McNeill talks about his time as a labor editor in Racine, Wisconsin. It’s hard to read now: if anything, things are worse, and one senses that a lot of concerned people have simply thrown up their hands.

But: it’s good for you. And: there’s a lot here that’s useful. Tom Frank’s lead-off essay, a survey of labor writing through the ages is still relevant:

As a rule, advertising, the highest form of information-age cultural production, intentionally avoids discussing where products come from. In a time in which, we are told, style and image transcend all – both for corporate marketers and ourselves as consumers – essays like Edmund Wilson’s long description of the brutal facts of automobile production in “Detroit Motors” come across as nothing short of revelation. For a writer in the 1990s to produce such a piece – insisting on the inherently local, inherently material facts of work in an age when the only journalistic game in town is to wax blissful about the cyber-universe is eclipsing the analog world – would be almost willfully contrary. (p. 11.)

Change the date and it still works. Tom Vanderbilt’s “The Gaudy and the Damned” seems to have discovered a source for Mad Men, reading Chicken Soup for the Soul at Work (still in print, in turns out):

One story, titled “Santa comes to Joan,” caught my eye: “Every office has a Joan, or should have. She’s the one everyone looks to when the workload gets too heavy. She’s the one with the good story and the ready laugh. For our Christmas party, she’s the one who transforms our sterile corporate conference room, Christmas after Christmas, with tiny white lights, real teacups, teapots and plates she had brought from home.” (p. 15.)

And reading Josh Mason’s “Three Scenes from the Bull Market” now, one is surprised to discover that Jim Cramer of Mad Money and the real estate bubble got his start at the New Republic, where he suggested that laid-off workers could be quieted with stock options. Still hilarious, and available online at the SEC, is Wired‘s first, failed IPO, excerpted by Doug Henwood; they had operated at increasing loses for their first four years, but they were hopeful about making a lot of money off of suck.com in the future. Another prospectus, from Vans, touts how they’ll be more profitable as they’ve moved all their shoe manufacturing to South Korea.

As its title suggests, Jim Frederick’s “Intern Camp: The Intern Economy and the Culture Trust” looks at the culture of interning, then in a relative infancy. Obviously interning for for-profit corporations is a terrible thing, and there have been any number of pieces written about that. But Frederick’s piece is notable in that it examines the legal basis for internships:

There is, however, another exemption in the FLSA [the Fair Labor Standards Act, passed in 1988 (!)]. Vaguely worded, it concerns “trainees,” or the oddly redundant “student learners.” It allows for-profit institutions to pay short-term employees less than the minimum wage if they are there in an educational capacity. The Department of Labor requires that six criteria be met before it considers someone not an “employee” but a “trainee” exempt from the FLSA: The training is similar to that one would get in school; the training is for the benefit of the trainees, not the employer; the trainees do not displace regular workers; the employer derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the trainees, and may even incur some loss; the trainees understand that they are not entitled to a job at the conclusion of the training; and the trainees understand that they are not entitled to wages for the time spent in training. (p. 53.)

Frederick points out that some industries (banks, law firms, tech companies, engineering companies, and federal agencies) generally follow this; it’s abused by the glamor industries, fashion, architecture, and publishing, which use internships as a source of free labor. There’s a distinct class-based element to intern labor: it’s only relatively affluent young people who can move to New York and work for free in the hopes of getting a job down the road. (David Foster Wallace, more attuned to class differences than one might expect, would get this exactly right in “The Suffering Channel” where he describes a hierarchy of extremely well-dressed interns and the discomfort of his protagonist, working class reporter’s discomfort, with them.) One wonders how much the publishing industry has been hollowed out by two decades of reliance on interns: somebody should be looking at this.

At the end of the book, Robert Nedelkoff’s “Remainder Table” takes a look at the two books of the novelist Alan Kapelner, still neglected. I don’t know Kapelner’s work; LibraryThing reports that All the Naked Heroes was in the libraries of Carl Sandburg and Marilyn Monroe and Lonely Boy Blues was owned by Hemingway. I’d love a compilation of Nedelkoff’s “Remainder Table” columns; the books in them that I’ve tracked down have been worth the time.

And finally, Damon Krukowski had taken on the job of poetry editor with this issue: the selection here focused on poems about labor. Two poems, by Lizinka Campbell Turner (“Distinguo,” poorly scanned but in its original context here) and Edwin Rolfe (“Asbestos”), were rescued from The Liberator (1918) and The Daily Worker (1928); there’s also Kenneth Fearing’s “X Minus X” from 1934 plus Muriel Rukeyser’s “Metaphor to Action” from 1935. It’s an interesting selection, not least because it works well with the rest of the issue: one forgets that there was a sustained tradition of poems about labor, and that labor magazines published poetry. Somebody must have made a good anthology of this by now; I’m impressed that all four can now be found online.