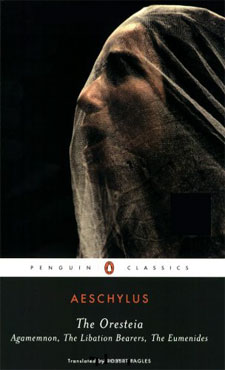

Aeschylus

Aeschylus

The Oresteia

(translated by Robert Fagles)

(Penguin, 1975)

One of the problems of being an inveterate snob is finding a suitable book at airport bookstores. The severity of this problem varies from airport to airport: there’s a shop in Chicago-Midway where one can find Coetzee and a good selection of the Dalkey Archive, while I’ve seen copies of Finnegans Wake languishing in the “literature” section at one shop in Minneapolis/St. Paul. (The bleak situation one generally encounters is very much an American phenomenon: Canadian airport bookstores have very different contents. I once bought the latest Hardt & Negri in the Victoria airport.) But one always wants something new in an airport. I have a handful of books packed in my bag, to say nothing of the stack of unread Times Literary Supplements, but the second quarter of A Dance to the Music of Time isn’t engrossing me, and the idea of starting another Henry Green in the midst of so much stimulation seems daunting. Thus, a trip to the Hudson News in the Delta terminal of JFK yielded this, from the “classics” section, where it fell among that strange selection of books and authors that comprise the American high school canon. One notes that Edith Wharton is being pushed heavily right now alongside the Jane-Austen-with-monsters books.

What one particularly wants in an airport – besides the possibility of catching up on something one should by rights have read long ago so one can feel virtuous – is something with a long introduction, so it can be read while distracted: the virtue of a long introduction is that it’s likely to be digressive, letting the mind of the reader wander. Agamemnon doesn’t arrive until page 99 of this edition. This is exactly what I want in an airport book. One quickly realizes, however, that this is not actually an ideal airport book. I don’t imagine that this is the scholarly edition of the Oresteia that anyone really uses in English; but it’s not exactly an edition meant for reading. The commentary overwhelms the plays, when they finally arrive: it’s nice that there’s so much of it – there’s a note every ten lines or so, and it’s possible that there are as many words in the endnotes as in the actual text – but this isn’t very helpful for someone coming to the plays themselves for the first time. Maybe it’s too much to expect the classics to read themselves.

This is a book, then, that I read in the following manner: first, I worked my way through the introduction, then I read each of the three plays twice, first stopping to read the notes as they appeared (callouts to the endnotes don’t exist, so one needs to keep flipping back and forth to see if you’ve missed something); then a second reading of the play straight through. Finally, back through the introduction again. This isn’t the best way of reading a book, but the slowness is necessary. Fagles’s version of these plays doesn’t provide much in the way of stage directions, or clues as to what backstory might be in play. In addition, his syntax in English appears to follow the Greek (which I don’t know), so one finds passages like this, in The Libation Bearers, from a speech given by Orestes, who has just introduced himself to his mother as a stranger:

. . . I met a perfect stranger, out of the blue,

who asks about my way and tells me his.

Strophios,

‘Well, my friend,’ he says, ‘out for Argos

in any case? Remember to tell the parents

he is dead, Orestes . . .

promise me please

(it’s only right), it will not slip your mind. (660–666)

The quoted speech goes on for five more lines. It’s difficult for the reader who doesn’t entirely know what’s going on to scan exactly what’s going on here: on first read, “Remember to tell the parents he is dead, Orestes” sounds much more like a statement being addressed to Orestes rather than being about Orestes. I imagine this works better in an inflected language; as English prose it doesn’t work very well, though there’s a certain poetic sense to it.

It’s hard to imagine staging this translation as a drama on a stage: too many of the speeches are similarly inscrutable. This isn’t a dramatic translation: the virtue of this translation is its poetry, which does occasionally sing when it can be uncoupled from the history that entombs the works themselves. In Agamemnon, Cassandra stands out to the casual reader: she is is both a sympathetic character (abducted from her home, gifted with clairvoyance that goes unbelieved) and is given some of the best imagery. Here she sees Clytemnaestra murdering Agamemnon:

Look out! look out!—

Ai, drag the great bull from the mate!—

a thrash of robes, she traps him—

writhing—

black horn glints, twists—

she gores him through!

And now he buckles, look, the bath swirls read—

There’s stealth and murder in the cauldron, do you hear? (1127–1131)

There’s Yeats here, obviously: it’s hard for me whether that might be Fagles’s interpolation of “Leda and the Swan” or whether Yeats was taking his imagery from an earlier version of this play. Fagles’s introduction, with epigraphs from Hart Crane and D. H. Lawrence, makes me suspect the former.

There’s a foreignness to these plays that’s hard to get around. It’s hard to understand, for example, why Orestes and Electra, in The Libation Bearers should be dead set against Clytaemnestra, their mother, for having killed their father, Agamemnon; in the first play, Agamemnon himself killed their sister, Iphigenia. Both parents consorted with others; but why killing a husband should be a more serious crime than killing a child is unclear in our distance. There seems to be an internal logic to their behavior, but it’s hard to suss out exactly what that is, even with the aid of the notes: when the gods appear in The Eumenides, they seem to be as capricious in their arguments as the humans. Everything is pitched up to a phenomenal degree: everyone seems to be insane. It reminds me, working through things in the wrong order, of Andrzej Żuławski’s On the Silver Globe, where the space colonists similarly fall into paroxysms of madness, shouting about faith and duty to the family, and end up killing each other. In his introduction, Fagles describes this trilogy as being a “grand parable of progress” (the words are originally Richard Lattimore’s), describing the formation of the state from the age of heroes; one might see that, but there’s still something strange and distant here. It’s hard for me to get past that; probably that’s my own failing.

Pingback: march 11–march 16 « with hidden noise

Pingback: homer, “the odyssey” « with hidden noise

Pingback: MetaFilter | Community Weblog

Pingback: Reviews: The Oresteia: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides by Aeschylus | LibraryThing

Pingback: You've been Stumbled!

Pingback: Colin Marshall: The trend piece term would be "microcritics"

It is your own failing. What a simpering little non-artist you are. You have the privilege to experience the superhuman passions of Greek tragedy, then complain because they at a distance from your spare time buying Penguins in airports and thumping such insipid critiques out of your keyboard. The foreigness you are unable to get your head around? As usual, it is an artist exulting in his art, it is that penchant for excess, hyperbole, exaggeration and the out of the ordinary, characteristic of all the outstanding masters of imaginative writing. Seriously, stop writing about your reading, you simply do not have the aesthetic sense required for the appreciation of masterpieces. Why on Earth is everybody angry and killing each other? Well, you couldn’t fashion much of a drama out of knitting one another wooly jumpers, could you?