Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. Delany

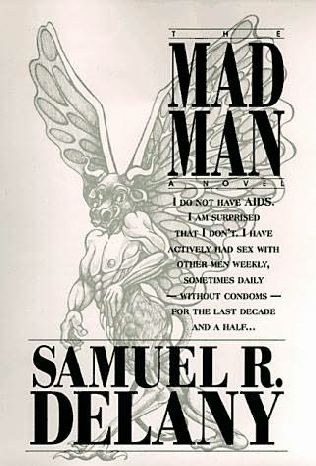

The Mad Man

(Richard Kasak Books, 1994)

The Mad Man seems to be more neglected than most of Delany’s books, perhaps because, like his more recent Dark Reflections and Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, it’s fiction but with the science fiction kept to a minimum. The Mad Man‘s protagonist, John Marr (named, presumably, after a sailor remembered by Melville in one of his poems) is a grad student living in New York from the late 1970s to the early 1990s; he’s attempting to write a biography of a brilliant (and imaginary) Korean-American philosopher somewhat reminiscent of Wittgenstein whose work came to a premature end when he was stabbed to death in a bar frequented by hustlers. John Marr’s life inevitably comes to resemble that of Timothy Hasler; his biography never really happens, though he does solve the mystery of what happened to Hasler. In its broad outlines, the literary detective story seems overly familiar, though perhaps this wasn’t quite the case in 1994.

While the plot does provide a comfortable framework for The Mad Man, there isn’t quite enough of it to hoist the novel’s 500 pages; for most of that, it seems incidental to what’s actually going on in the book. Though it’s written well enough, this book isn’t easy to read because of just how graphic it is. Marr has a taste for extreme behavior, particularly with homeless men; there are extended descriptions of urolagnia and coprophilia. While the book is certainly prurient, its pornographic aspects would appeal to a presumably small audience, and it’s hard to imagine that it’s written primarily to titillate. Nor does Delany’s aim seem to be to shock: the situations described might arouse repulsion or disgust in many readers, but that isn’t really a reaction that can be extended for twenty pages at a time, as frequently happens here.

What Delany seems to be doing, rather, is to use fiction as a method of presenting ways of living and behaviors that are unfamiliar to many in his audience. This didactic aim is shown early: Marr writes a long letter to Sam, a sheltered ex-girlfriend married to a professor who gives up his work on Hasler out of disgust. Sam has written Marr a letter of concern about AIDS (the year is 1984); Marr finds her response tokenizing, but rather than angrily calling her out, he writes her a letter of 72 pages narrating his sexual life as he lives it. Sam tokenizes because she doesn’t actually understand anything about how John Marr lives his life; if she is to change, she needs to know what he’s going through rather than sensationalized accounts in the news and inadequate depictions of gay life in the media that she’s seeing even in an educated context. As a method of attaining realism, the epistolary strategy quickly strains credibility (as it has in fiction since Richardson); but Sam is a cartoon of a character. She serves more as an idealized stand-in for the reader: against all odds, Marr’s stratagem works, and five years later she replies noting that she’s ditched her creepy husband for a female lover and apologizing for her heteronormative views.

What comes through to the reader is Delany’s capacity for empathy. Marr’s desires seem extreme: the men that he is sexually interested in tend to be homeless and in rough shape, drunk priapistic exhibitionists coated in a staggering variety of bodily fluids. To someone who doesn’t share Marr’s desires, this seems almost ludicrous: there are the sort of people everyone moves away from on the subway because of their smell. Marr gives away little of his back story; we can’t psychologize a motivation for his desires. (At one point, indeed, he resists this: a bartender at a gay bar claims that he, like many of his patrons, is gay because he was molested as a child; Marr says that nothing like that happened to him.) What’s left to the reader is to judge Marr and his companions based on their acts: and while these are presented in a way that suggests degradation, Marr’s narration makes it clear that he feels a great deal of affection for his partners; his urine-soaked relations with one man even blossom into domestic contentment at the end of the book.

While this is a gritty book in many aspects, presenting a street view of the ravages of AIDS in New York in the 1980s, there’s also a strongly utopian aspect to it. Marr and his lovers genuinely care about each other; the sexual adventures almost uniformly end happily. Almost everyone Marr runs into turns out to share his predilections, which almost certainly also defies the laws of probability. (One notes, of course, that Marr’s letter to Sam points out that he withholds a great deal whenever he presents himself to others, even in the explicit letter that he’s writing; this theme is echoed across the book.) But one of the things that comes across most strongly in the book is the sense of community that sexual contact brings about: Marr’s encounters with strangers cut entirely across the lines of class, society, and race. In a way, they’re ideal citizens, even if they inhabit a less than perfect society.

Aspects of this book might seem overly familiar to those who have read Delany’s non-fiction: John Marr’s reaction to the AIDS crisis seems similar to Delany’s as presented in 1984: Selected Letters, and the descriptions of porn theaters is much the same as in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, including the rhetorical device where Delany patiently explains what goes on in the porn theaters to a straight woman. Delany insists here and elsewhere that oral sex doesn’t transmit AIDS, and complains that serious studies haven’t been done on the sexual practices responsible for spreading the virus. For what it’s worth, I read the first edition of this book; a revised edition came out in 2002, though I’m not sure what the changes were, and I’d be curious on what Delany thinks of this book now. (The particular copy I read came from the library of the Center for Fiction; if the library card’s accurate, it’s never been checked out, though Delany signed the copy in a shaky hand in 2011.)

Pingback: may 1–15, 2013 | with hidden noise