Chart Korbjitti

Chart Korbjitti

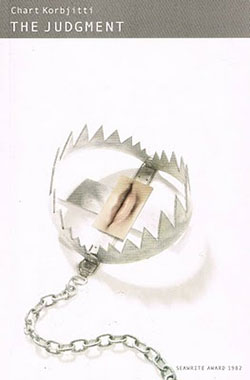

The Judgment

(translated by Phongdeit Jiangphatthana-kit & Marcel Barang)

(Samnakphim Hon/Howling Books, 2007; originally 1981)

There is neither a tremendous amount of information on Thai fiction in English – the Bangkok Post‘s occasional fiction reviewing being cheerfully incompetent at best – nor does much Thai fiction in translation get published or distributed outside of Thailand, so I thought it might be useful to have a project of haphazardly reading through what I can find here. Chart Korbjitti (ชาติ กอบจิตติ), for example, is one of the best-known of contemporary Thai writers, having won the SEA Write prize twice; this book was turned into a film, and he’s been translated into French and English. But he’s published through his own press, Samnakphim Hon, or Howling Books, based in Pak Chong in the northeast; Thai publishers haven’t generally been adept at securing distribution outside the country, and I suspect his books aren’t read very often in English if only because no one outside the country knows that they exist. While a couple of used copies turn up on Amazon, I’m not sure how one would go about getting print copies outside of Thailand; however, thanks to industrious translator Marcel Barang, a PDF version can be bought or sampled here. There’s a useful introduction by Marcel Barang that contextualizes the novel in the Thai Modern Classics edition of the book (1995) that isn’t in the Howling Books edition (I’m not sure about the PDF); it’s worth tracking down if possible.

Chart concerns himself with the people of Isan, the northeast of Thailand. It’s not a milieu that’s familiar to most Western observers of the country, though the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul might change that; certainly, it’s not the way the government seeks to present the country.

No Way Out (1980, translated 2003 by David Smyth) is more compressed and more unremittingly bleak, approaching almost the level of Jude the Obscure‘s bathetic “Done because we are too menny”. There, the cause of the problems faced by the poor is clearly defined as predatory lenders selling debt without regard for the human cost; the protagonist is sold into effective slavery on a fishing boat (a problem still rampant in Thailand), his wife and daughter are forced into prostitution, the luckier son goes to jail. As the protagonist is about to commit suicide, he pins his fate on his decision to borrow 3000 baht (around $100) from his employer to build a house; can this really be considered hubris? He ends by blaming karma:

Boonma didn’t blame anyone at all. He wasn’t even angry with anyone for making his family end up like this. He blamed only himself. He was angry only with himself for being born poor. He didn’t know why poor people such as him always encountered such misfortune. All he knew was that life was a matter of karma, of paying off the debt for the sins of past lives. (p. 129)

These concerns also animate The Judgment (คำพิพากษา). Fak, the protagonist, is his father’s only son; he works as a janitor for his village’s school. His dream had been to become a monk, but he left the temple to support his father; when his father dies, his sense of duty leads him to support his father’s second wife, who is mentally unstable and tends to expose herself to people. The village takes it for granted that Fak has taken his stepmother has his wife; Fak, however, is trying to hold on to his virtue so that, when circumstances permit, he can return to being a monk. But he is worn down; in fairly fast order, he takes up drinking, becomes a drunk, and loses his job.

Drinking is a sin, prohibited by monastic vows; so is killing living things, and a turning point in the narrative is when Fak, at the insistence of his co-workers, kills a dog that’s assumed to be rabid. This is a socially useful act, and Fak is congratulated for it, but one that’s spiritually detrimental: Fak sinning by killing the dog means that no one else needs to sin. (There are, for related reasons, large numbers of stray dogs in Bangkok; and while it is not a sin to eat an animal, it is to kill one; butchers are hidden away.) And while Fak is striving to honor his father by taking care of his widow (who has no family and cannot be left on her own), the village assumes the worst of him and no one turns up for his father’s cremation. Fak is befriended by the town undertaker, a man comfortable with his own low status; trying to comfort him, the undertaker introduces Fak to alcohol and spells the way to a speedy (perhaps unbelievably so) descent into alcoholism.

Fak’s troubles intensify: he is tormented by the village children and accidentally hurts one of them; the boy’s father and his friends ambush Fak and beat him severely. Finally, Fak goes to the school headmaster with whom he has been storing his money; the headmaster lies and claims that he never held any money for Fak. Fak publicly accuses the headmaster of cheating him and is laughed at by the village; he is put in jail, though the headmaster lets him out as a show of largess. His friend the undertaker abandons him for fear of repercussions from the villagers. Moneyless and friendless, Fak starts throwing up blood and dies in very short order. The headmaster arranges for his cremation, but does it in a deliberately shoddy manner. Fak’s stepmother is captured and sent to an asylum in Bangkok.

There’s a similarity to Western novels of the individual against society – Thomas Hardy’s later novels come to mind, as do Jack London’s Martin Eden and Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, and, probably at some remove, Dostoevsky’s holy fools. Though it’s written much too late, The Judgment seems to fit squarely into the conventions of the naturalist novel. My hesitation is because it’s hard for me to make sense of the novel’s relationship to religion and social order: is Korbjitti’s book coming out against traditional Thai society? Certainly it’s the source of Fak’s problems. The undertaker explains to Fak:

If all the people in the village were lined up according to their status, I’m sure I’d be at the end of the line because I’m really inferior – just an undertaker. But right now – you and me are birds of a feather and it’s a toss up who’d be at the end of the line. When you were a novice, you were at the head of it, and you had no idea how the people at the other end felt. (pp. 151–2.)

Hierarchy is extremely important in Thai life. (And in its language: one of the things that’s interesting about the Thai language are the sheer number of different pronouns for speaking to people of different status.) And while one’s position in the hierarchy isn’t totally fixed in stone – any male can become a monk and thus higher status; no analogue exists for women – it tends to be a conservative force. The headmaster stands at the front of the village line; it is impossible for the village to imagine that he could have cheated Fak. Karma plays into this hierarchy: one is born low status because of sins in one’s past lives. Fak goes against this, by actively blaming people – the headmaster’s cheating him – rather than fate; for this reason, his punishment by the village is intensified. I can’t tell, however, how clearly religion is meant to be the cause of Fak’s suffering. No real alternative is presented; the supplanting force of capitalism, in the form of consumer goods and associations with Bangkok, is presented dismissively. No Way Out takes place in Bangkok and religion plays much less of a role in comparison with the economic system; the consequences are the same.

Pingback: Anonymous