Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guin

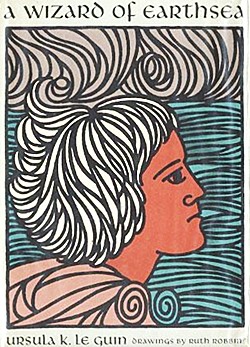

A Wizard of Earthsea

The Tombs of Atuan

The Farthest Shore

Tehanu

Tales from Earthsea

The Other Wind

(originally Parnassus Press, 1961–2001.)

It’s been a while since I’ve taken an intercontinental trip by myself, and I’d forgotten what a useful space for a certain kind of reading that can be. I’d hoped to get further in Henry James (I am bogged down in The Other House, which I’ll get back to eventually), but I had Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea books on my phone, and they lent themselves to the kind of distracted reading one does on planes and in airports.

I should start by saying that I didn’t read these books when I was young and probably should have read them. I have read the Le Guin that everyone talks about besides these and I do find myself thinking about The Dispossessed and The Word for World is Forest (as heavy handed as that book is). She’s an interesting writer and writes the kind of science fiction that I care about – I do still feel guilty about not liking more science fiction than I do for reasons I still can’t quite explicate – and everyone has nice things to say about these books, but I’ve had to drag myself to them, which I think is because they’re about dragons and wizards.

I have not, since young, read many books of dragons and wizards, and I’ve largely felt reticent to read more. I dutifully read Gene Wolfe, which wasn’t really to my taste, and the last book of Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth sits unread and unloved on my phone waiting for some future transportation breakdown when I somehow have nothing else available. Smart people like these books, and I wish I could like them, but I don’t. I do like Delany’s Nevèrÿon books, but what he’s doing there seems a little at odds with what other people enjoy about the genre. So it did seem like if anyone could do something with the genre that I would be able to appreciate I might be Le Guin. The results are mixed. Or, more accurately, the results are mixed for me. There are other people who like all of these books: they haven’t failed to find an audience.

The fifth of these books, Tales of Earthsea, is a collection of short stories and novellas that closes with something that might be termed non-fiction: a historical and sociological overview of the world Le Guin created in these books, providing a great deal of background information that might clarify what’s previously been read. This is very lovingly done; it’s also the locus of what makes this kind of work uninteresting to me. Le Guin has created a geography and peopled it; there are some interesting ideas in there (the Platonic-seeming idea of true names, for example, or her characters’ views on race, which aren’t exactly what you’d expect in a white-authored book from the 1960s) which have previously been worked out. As situations for characters to react to, they can be interesting. By themselves, they demonstrate a degree of originality, though also an indebtedness to previous creators of fantastic worlds: I am not the person to draw out the genealogy of Le Guin’s dragons, though at this point in time they seem overly familiar.

The createdness of the world – something that Le Guin’s pocket history amply demonstrates – also gets to another aspect of the work, and maybe all fantastic fiction. Le Guin explicitly declaims religiosity in Earthsea, but the supernatural elements preclude a purely rational creation of her world. Obviously Le Guin made it; but this world operates according to principles that aren’t strictly mirrored by our world, and this makes for frustrating fiction. Dragon or wizard can be deus ex machina as needed. Why do dragons act that way? No one knows, they just are – and this reader can’t help wondering if they are as convenient for the narrative.

With that in mind, I’ll say that the first and third books of the series did very little for me, as to my eye they followed the conventions of the wizardly quest too closely. (Again, perhaps these conventions – including but not limited to goatherds of promise, wizard schools, wizard battles, nebulous darkness, wizard quests, rings of power – became overly familiar after Le Guin; one should not blame an author for her followers, though sometimes one can’t help doing that.) They are not with the the occasional striking image – the brother and sister marooned far out to sea almost without language, for example. The series becomes interesting to me in the second book, The Tombs of Atuan, which convincingly describes a young woman growing up as a priestess in an illiterate cult; the prison of belief is described in a way not unlike the work of Brian Evenson. The book becomes less interesting in the second half, when she is rescued by a heroic and long-suffering wizard.

The fourth book in the series was written considerably after the first three and is interestingly revisionist. The first three books are, with the exception of the first half of the second, male dominated. Wizardry is exclusively an occupation for celibate males. The fourth book, Tehanu, returns to the protagonist of the second, now middle-aged and leading a domestic life; we see the world Le Guin has created through different, considerably more interesting eyes. Witches suddenly exist. Men behave badly, and one realizes that life for women and children in a male-dominated pre-industrial world is not all it might be. Wizards can be useful, but they tend to be self-absorbed and not reliable. Much of the narrative propulsion of the fourth book comes from Ged, the lead character of the series, coming to terms with having lost his wizarding power. The fifth book, a collection, continues the revisionist tendencies of the fourth, having mostly women as its protagonists; the damage heedlessly done by men is a primary focus. And the sixth takes on a familiar group quest motif, bringing together a number of characters previously met to bring the series to a comfortable end point. There’s interesting thematic work happening, but it didn’t do very much for me, perhaps because I’d just read the other five books very quickly.

Were I to re-read, I would come back to Tehanu and The Other Wind: Le Guin’s later books have more for me than the original trilogy. The second half of the series, not coincidentally, is considerably more adult than the first. Already existing characters are complicated; the simplistic universe of the original books is rejected and revised. One could historicize: the person writing the later books knew more than she did when she wrote the earlier ones; plenty of well-intentioned people were writing things in the 1960s that haven’t aged well. That revision is what interests me here. I still don’t particularly care about the world-building; maybe if I’d read these books when younger I would have?

I wonder if Doris Lessing’s Canopus in Argos series would be more attuned to your SF or fantasy tastes? Or perhaps Austin Tappan Wright’s Islandia?

Good suggestions! Islandia is on my list (though I don’t think I’ve ever actually seen a copy) because of a Le Guin essay on utopianism. I think I started Canopus in Argos in high school – at least I got the books out from the library? – but I never got very far. Maybe worth trying again.