Jerzy Kosiński

Jerzy Kosiński

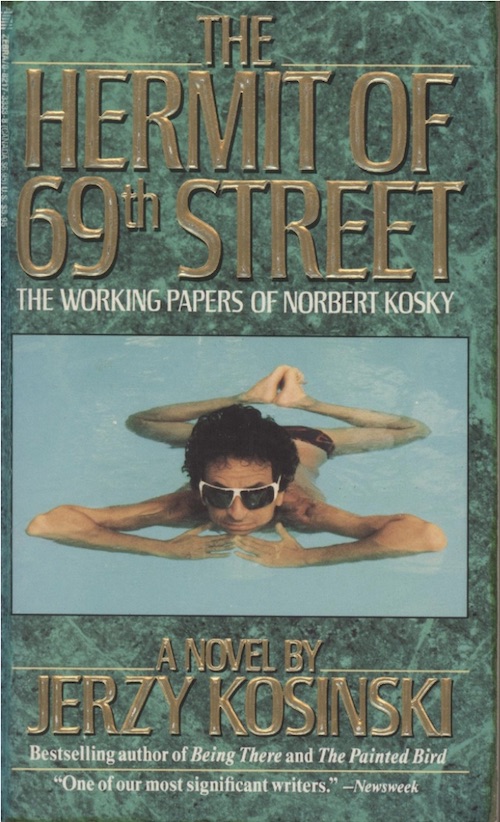

The Hermit of 69th Street: The Working Papers of Norbert Kosky

(Zebra Books, 1988, 1991)

I can’t imagine there’s a great demand for the work of Jerzy Kosiński at this point in time: he’s remembered first as a vague fraud and second as the writer of Being There. (Maybe the latter, providentially plagiarized, will lead to a reassessment at the present political moment?) The Painted Bird used to be omnipresent in used book stores and presumably was still finding an audience of sorts; but the decline of used book stores has probably hurt its chances of finding an unsuspecting reader. I suspect there’s an edition of Steps out with a contrarian David Foster Wallace blurb, though I don’t know if even his endorsement would save the book. There’s certainly no demand for Kosiński’s last novel, The Hermit of 69th Street, though it’s been on one of my to-read lists for a while; and I was happy to come across an embossed mass-market paperback (printed a month before the author committed suicide) in a used book store in Los Angeles.

It is hard to imagine a stranger mass-market paperback. Almost every page is footnoted. The subtitle (“The Working Papers of Norbert Kosky”) gives a sense of the conceit: a writer, blatantly a stand-in for Kosiński himself (p. 10: “the year 1966 saw the publication of the unexpurgated edition of his first fictional tale, about a little Gypsy or Jewish toddler during World War II”), is trying to write a book, and (having been accused of citational looseness in the past) is citing everything for his editors/fact checkers/proofreaders. The text is larded with quotations, some real, some imaginary, bolded and italicized at whim; their citations are capricious and often willfully annoying.

I don’t know enough about Kosiński’s life to know exactly how close this matches or doesn’t match his own; the promotional blurb in the front matter of the book says that Kosiński dubbed it an “autofiction” (citation needed, though the word is repeated on the back cover; looking into what the word “autofiction” meant in 1992 might be useful). I’ll also say that I don’t particularly care that much about Kosiński’s hoaxing or status as a fake (not mentioned in the book’s promotional elements, though they would have been well known when this was published), though it’s hard to escape how much this book seems like an apologia: this is manifestly a book about fact-checking and the process of making books. At the same time, the book has a cavalier disregard for actual fact-checking. On p. 23, for example, the narrator (who is not Kosky) reports:

Thus among its newest sex ads, the seven character cryptogram USA-GIRL is, in fact, 872-4475, while the innocent looking 825-5739 can mean ISS-SINS and JKJ-KISS turns into 955-5477.

Looking at a telephone keypad (or even a dial!) would have shown anyone that while the first is correct, the second and third aren’t close to being so. There’s the same looseness with the book’s many citations. A representative passage:

Kosky trusts Dustin’s intuition. It is purely American since, as his name indicates, Dustin comes from a very pure Boston family. Propelled by an inner wind, Reverend Dan Beach Bradley Borell,(4) Dustin’s most revered ancestor, bravely sailed from Massachusetts all the way to Bangkok, where he – a typical Boston Brahmin! – hoped to introduce the Gospel to Siamese Brahmans – the all-time champs of what is latest in the art of meditation – to start a Meditational Church in Siam. (p. 103)

There’s a footnote:

4. The Reverend Dan Beach Bradley, M.D., author of Medical Missionary in Siam, 1836–1873, op cit., was “one of the many proper Boston Brahmins fascinated by the Orient and by its rigorous – almost puritanical – physical and mental discipline.” (Kosky, A Floating Lotus Lecture, 1986).

I choose this passage since Mr. Bradley and his two wives are buried five minutes down the street from me in the Bangkok Protestant Cemetery, which is why I happen to know about him. Today anyone can go to Wikipedia and learn about him; however, when this book was written I suspect he was unknown to almost all of Kosinski’s readers. There are a few odd things to note here. While Bradley studied at Harvard and did sail from Boston, his family was from New York, not Boston Brahmins; and his last name was not “Borell”. (As far as I can tell, this is done so that Dustin, “the nation’s supreme literary accountant,” can be referred to as “Mr. Beach Borell”: there are a lot of puns in this book.) A Floating Lotus Lecture is fictional; Medical Missionary in Siam, 1836–1873 is cited a bit oddly, as it’s probably Abstract of the Journal of Rev. Dan Beach Bradley, M. D. Medical Missionary in Siam 1835–1873 a posthumous collection published in 1936. After the quoted text, Bradley exits the book’s narrative for almost four hundred pages, until he calls the protagonist, who answers “Good to hear from you Reverend Dan” and there’s another footnote:

8. Rev. Dan Beach Bradley, M.D., “had an impressive number of accomplishments: He played a leading role in the introduction of printing to Siam; he was the first person to perform a surgical role in that country, and, after years of futile experimentation, in 1840 he performed the first successful vaccinations for smallpox. His was the first newspaper to be published in Siam, and it was he who printed the first royal decree (against the sale of opium) that came off a press in Bangkok. Most of all, he was a respected friend of the Siamese people, and through his journalistic enterprises in particular, he looked after Siam’s national interest in its relations with France and England.” From William L. Bradley’s Siam Then: The Foreign Colony in Bangkok Before and After Anna (1981). (p. 488)

What, exactly, is Reverend Bradley doing here? I will assume that Siam Then came into Kosiński’s library at some point and was raided for the quotation. Certainly the life and work of Anna Leonowens – whose deeply fictionalized memoirs The King and I were based on – seems more apropos to Kosiński’s project, though she’s only mentioned in the citation. I can’t make sense of what he’s doing here: and in this, he’s not unlike many of the book’s seemingly arbitrary quotations. Kosiński’s citations are willfully capricious and often seem a bit off (e.g. the text refers to “such films as Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985)” and a footnote reads “Shoah, an Oral History of the Holocaust, the complete Text of the Film by Claude Lanzmann, preface by Simone de Beauvoir, Pantheon Books, N. Y. 1985”); verifying them wouldn’t be terribly hard at this point in time, but it’s not clear that it would be particularly useful.

There are a huge number of these citations; I can’t tell that they add up to anything, but the effect is that of a massive commonplace book, a sense of what Kosinski the person was reading. There’s a hint later in the book:

His head swimming from the overflow of seminal thoughts (“the brain’s semen” Jay Kay) Kosky takes out from his ever present shoulder-bag a bunch of Plot-Quote cards, “the portable table game of literary invention,” in the words of the nameless inventor. Each card contains a short fragment from a certain novel. The body then becomes, as it were, a Book of Revelation. In it is condensed much of out secret history. In it are latent the necessities of our future. (Gina Cerminara, op. cit., p. 69) (p. 400)

The bold text is of course Kosiński’s. Perhaps this is an admission of the process that constructed this book: quotations chosen at random and assembled to construct a book. Another quote:

Writing is creation. The Hellenistic period saw the birth of the novel. The earliest complete specimen, that of Chariton, is not later than the second century of our era, and the genre is certainly earlier. (A.D. Nock) Kosky cannot write his own story telling story – a full length novel at that – without writing, one way or another, about the very lengths to which a storyteller must go in his various trials of the writing process. Here, don’t confuse process with trial, particularly not the writing process with putting a writer’s writing – worse yet, a writer! – on trial. And writing means to him, skoaling life in the sizzling Swedish fashion since it is the Swedes who, awarding yearly the Nobel prize to a novel (not the other way around printer!) consider fiction – that is, a novel, or even a novella – more powerful than dynamite invented by Nobel. (p. 377–8)

Again, the bolds and italics are Kosiński’s, as is the capricious punctuation; I’ve left out a long footnote that’s another quote from Nock’s book about the recognition plot. Here we almost get an interesting defense of the writer’s ideas about creation and originality before it gets lost in dumb puns and alliteration.

* * * * *

This is a tiresome book. (This is at least partially intentional: pedantry is key to what Kosiński’s trying to get at, though he undercuts himself by being unreliable.) Every character speaks in exactly the same way, using dumb puns, copious and recondite literary quotations, and ending half of their sentences with exclamation points, which, combined with the often randomly sprinkled-in quotations, sometimes gives the reader the impression of stumbling upon a novelization of a particularly depressing Mary Worth. Every female character is a sex object; the male characters all leer or don’t lear because they are gay. Despite (or perhaps because of) the fetishization of copy editors and proofreaders, the book has been sloppily edited. The book’s length appears to be an effort to physically wear out the reader; not much would be lost if this were a tenth of its length.

Part of the interest of this book is its status as a roman-à-clef: a good literary historian could certainly dig through the characters and pin names on them. There’s a lot of score-settling. But at this distance, who really cares that, for example, Kosiński hated Hannah Arendt? At least as much time, if not more, is devoted to a recounting of the protagonist’s handing out of awards at the Oscars (as Kosiński did); there is a spirited defense of polo as a sport, and I will assume that Kosiński was criticized by someone for being a polo enthusiast.

One wonders whether the book was actually meant to be read: it almost seems like an act of self-sabotage in the tradition of Melville’s Pierre, a novel reworked to be about failure in the literary world. (Moby-Dick is mentioned in passing in Hermit, but none of Melville’s other works.) It also seems to prefigure David Markson’s work from Reader’s Block on – if you took out the narrative and only left the literary examples from this book, you’d end up with something very much like a Markson novel, complete with the writer’s overdeveloped sense of self-pity. (I suspect that Kosiński figures into those books, though I haven’t gone back to check.)

There’s the gem of something interesting here: an author accused of literary crimes attempts to defend himself in fictions as the worlds of the protagonist and the author increasingly intertwine. (Late in the book, for example, the protagonist watches the film version of Being There on television.) The protagonist identifies himself with various figures, literary and not – Bruno Schulz, Joseph Conrad (with whom he has a vexed relationship), Cagliostro (!), Chaim Rumkowski (!!!). There’s something unsettling with the way the horror of the Holocaust is presented as being a mitigating circumstance for literary misbehavior.

This is a strange book. It’s hard to imagine that this was pitched at the same general public who were the target of the ads in the back pages (a page and a half on the books from the woman who killed the Scarsdale Diet doctor; a page advertising books about an unfrozen Japanese aircraft carrier full of samurai fighting a Libyan madman; and so on). Certainly it could be read as an extremely prolix suicide note, and maybe there’s a rubbernecking appeal to that. But it feels like the work of a writer who was left to hang himself with his own words.