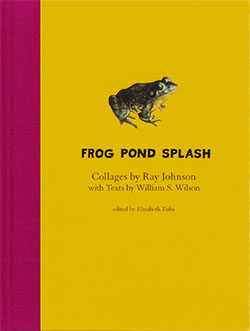

Frog Pond Splash

Collages by Ray Johnson

with Texts by William S. Wilson

edited by Elizabeth Zuba

(Siglio, 2020)

It’s hard for me to know what to make of this book.

This is a book that will be picked up by most people because of one of the names on the cover – Ray Johnson – and it is indeed an attractive compilation of some of his work. I don’t have a sense of where Ray Johnson is in the cultural pantheon of the moment; the newcomer might be advised to start with John Walter’s documentary How to Draw a Bunny, which captures something of Johnson and his world. The Johnson pieces in here are mostly familiar to me; the value of this work comes from the text about the images, excerpts from the correspondence of William S. Wilson. (His With Ray: The Art of Friendship is the other place I’d start thinking about Johnson’s work.)

What’s confusing to me about this book is entirely subjective: I was a friend of Bill Wilson’s from soon after I moved to New York until his death. Bill sent me mountains of correspondence, both by mail and email, easily hundreds, perhaps thousands, of pages. I am not particularly special in this — Bill corresponded with many, many people, most more interesting than I. The fragments of letters that make up this book could have been pulled from letters he sent to me; reading through this is an odd experience, like overhearing a conversation and not knowing whether you should be or not.

I met Bill at the launch party for Joseph McElroy’s Actress in the House – my roommate at the time had met him on a bus coming back from an anti-war march in Washington, and was surprised when I knew his work. Bill was the first person we met at Joe’s party; he was pleased I’d read his book of short stories, Why I Don’t Write like Franz Kafka, claiming, probably facetiously, that he’d never met someone who’d known him from his fiction. Bill was soon deluging me with correspondence; I dropped by his house in Chelsea on a semi-regular basis for show-and-tell sessions, where he’d show me art, talk about his writing, and invariably loading me down with books that he thought I might be interested in. Sometimes he’d throw parties and you never knew who would turn up – Carolee Schneemann and Alison Knowles, of course, sometimes Dorothea Rockburne, occasionally Billy Name, once a rather wrecked Ultra Violet. Bill was a bridge to a lost world: Nam June Paik and Lee Lozano had lived in his house. He’d shown Christo around the city when he first arrived. His mother, living in the Chelsea Hotel, had kept Valerie Solanas’s gun under her bed. Ray Johnson had brought Marcel Duchamp to visit.

But this is to the side. Bill had a Ph.D. in Chaucer, though he’d taught fiction writing (at the party when I met him, Rick Moody, a former student, suggested he was a malign influence); in the time that I knew him, however, he wrote about art: sometimes about his mother’s work, mostly about the work of his friends Eva Hesse and Ray Johnson. A key part of knowing Bill – from within a week of meeting him – was getting mail from him (with emails alongside mentioning that something was in the mail, often elaborating on mail that couldn’t have been received), and the sudden vertiginous feeling that one had been inserted into a complex network of nodes and edges that wasn’t entirely comprehensible. Part of this was being sent large pieces – ten or twenty pages at a time – of writing that he was working on, refining his thinking on Johnson or Hesse, never from the beginning, always in medias res; making sense of this was compounded by the inclusion of forwarded commentary on his previous writings by other correspondents, who might not be introduced. Part of this was Bill’s method: he wouldn’t explain something, opening it up as a space for discussion, something to be questioned and then explored.

And so the fragments that are in this book feel very familiar – I don’t think any of the particular texts were sent to me, though any of them might have been, and many of the themes feel familiar. Bill reworked ideas over and over, wringing them out: his interactions with Ray Johnson in particular, from their first meeting to his death, were reimagined and rethought again and again. Part of this is that Ray Johnson’s life was inextricable from his art: a piece of art could never be separated from the context in which it came into the world, the people or things referenced in it, and the interactions around it.

But there is a key difference here in seeing letters from Bill to other people excepted in a book and seeing letters to other people excepted as part of correspondence from Bill. A letter is usually sent to one person: it has a recipient in mind (though it may be waylaid, or passed along, or shared). A book is different: while it may be difficult to acquire a book for whatever reason, a book is (generally speaking) designed so that anyone may read it. (Analogously: email versus the open web.) A key point in communication with Bill was that a communication was valuable in proportion to the specificity of the recipient: something that could be said to everyone wasn’t as interesting as something that could only be said to one person. Bill was interested in the meaning that the person he was communicating with could uniquely convey to him – and he assumed conversely as well.

This isn’t dissimilar, of course, to what Ray Johnson was doing with mail art: he was interested in investigating the connections between people more than the people themselves. His collages read differently to different people: picking up one of Ray’s pieces, Bill could pull out endless chains of association because he was close to the maker; meaning that dissipates when the works are seen on a gallery wall — unless two people are standing in front of the work. One could put the collages in a book and provide a key to the meanings; but this is a very different kind of experience than direct connection with another person. A letter can’t help but reach its destination, Bill was fond of noting – then invariably encouraging me to read Derrida’s The Post Card, a book he had talked through with Ray Johnson.

I knew Bill for the last fifteen years of his life; in all that time he was writing furiously, working through the problems he had set himself. Every once in a while he’d publish something small – essays for catalogues, usually – but there was always the sense that these were fascicles of a greater whole. Certainly Bill could have written many books if he had wanted to – he wrote thousands of pages while I knew him. He didn’t, and I’m not sure how to read that – I’ve wondered about this since his death. Bill would invoke Harold Brodkey as the great writer in his life, and it’s temping to read Bill’s silence as fear of ending up where Brodkey did with The Runaway Soul. I think, rather, that Bill – as bookish a person as you can imagine – might have moved past the book as a form, finding the meaning that others would take from the publication of a book in the give and take of correspondence about his writing. Looked at this way, Bill’s correspondence is his great work; the hundreds of personal connections he had with the people he wrote back and forth to. (The book that more than any other gives a real idea of Bill is his friend L. S. Asekoff’s book-length poem Freedom Hill, a set of monologues in Bill’s voice.)

Everything exists to end in a book, Mallarmé said, and now more than ever the book is inevitable. The book is how knowledge makes its way across time; that isn’t something to be dismissed lightly. But a book, at the same time, is something frozen: snapshots of a life, of thoughts, of communication. None of this is to say that this isn’t a good book – it is that, and I’m glad that it’s in the world. But at the same time it’s not the book that Bill would have written – this is very much Elizabeth Zuba’s book, and she deserves credit for it – and its existence can’t help to remind me of the book that was to come and will never come, something like Mallarmé’s book.

And it’s a book that makes me think, ultimately, of Bill and my relationship with him inevitably colors my relationship with this book. Early on in talking with him, still full of received ideas from school, I ventured the opinion that he couldn’t write objective criticism about people that he had known, that there was no critical distance. I was, not for the first time, missing the point and saying something foolish.