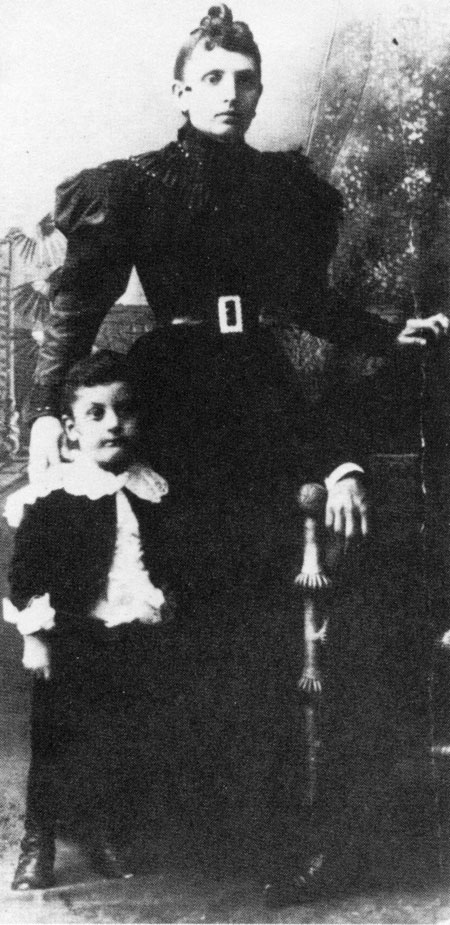

(the earliest known photo of Man Ray (with his mother) from his autobiography Self Portrait, p. 14)

(the earliest known photo of Man Ray (with his mother) from his autobiography Self Portrait, p. 14)

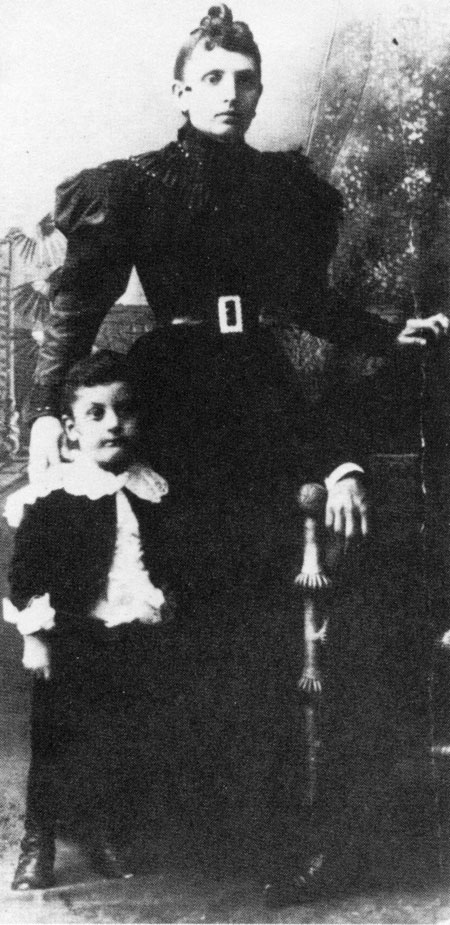

from the NY Times:

Lennon & Ono standing in front of George Maciunias’s U.S.A. Surpasses All the Genocide Records!.

Also worth mentioning if entirely unconnected: wood s lot has a collection of Michel Butor material.

“—Was it you I saw this afternoon? a little while ago?

—Me? Why? Where?

—Were you there, where they’re showing Picasso’s new . . .

—Night Fishing in Antibes, yes, yes . . .

—Why didn’t you speak to us?

—Speak to who? You? Were you there?

—I was there, with a friend. You could have spoken to us, Wyatt, you didn’t have to pretend that . . . I was out with someone who . . .

—Who? I didn’t see them, I didn’t see you, I mean.

—You looked right at us. I’d already said, There’s my husband, we were near the door and you were bobbing . . .

—Listen . . .

—You went right past us going out.

—Look, I didn’t see you. Listen, that painting, I was looking at the painting. Do you see what this was like, Esther? seeing it?

—I saw it.

—Yes but, when I saw it, it was one of those moments of reality, of near-recognition of reality. I’d been . . . I’ve been worn out in this piece of work, and when I finished it I was free, free all of a sudden out in the world. In the street everything was unfamiliar, everything and everyone I saw was unreal, I felt like I was going to lose my balance out there, this feeling was getting all knotted up inside me and I went in there just to stop for a minute. And then I saw this thing. When I saw it all of a sudden everything was freed into one recognition, really freed into reality that we never see, you never see it. You don’t see it in paintings because most of the time you can’t see beyond a painting. Most paintings, the instant you see them they become familiar, and then it’s too late. Listen, do you see what I mean?

—As Don said about Picasso . . . she commenced.

—That’s why people can’t keep looking at Picasso and expect to get anything out of his paintings, and people, no wonder so many people laugh at him. You can’t see them any time, just any time, because you can’t see freely very often, hardly ever, maybe seven times in a life.

—I wish, she said, —I wish . . .”

(Gaddis, The Recognitions, pp. 91–92.)

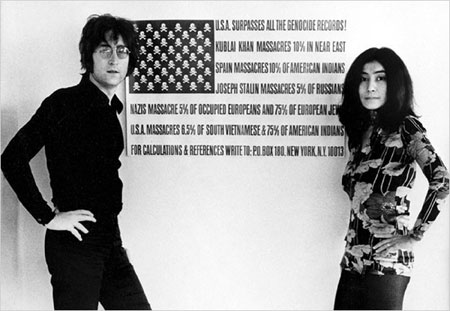

Marcel Duchamp retirant, à la requête des cubistes, son Nu descendant un Escalier du Salon des Indépendants.

Marcel Duchamp, Gabrielle et Francis Picabia, Guillaume Apollinaire assistant au théâtre Antoine à une représentation d’Impressions d’Afrique de Raymond Roussel.

(both images from La vie illustrée de Marcel Duchamp, avec 12 dessins d’André Raffray, written by Jennifer Gough-Cooper & Jacques Caumont, published by the Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou in 1977.)

Reviewed by Holland Cotter at the NY Times.

(Ardengo Soffici, BÃF§ZF+18 simultaneità e chimismi lirici, 1915. Part of A Tumultuous Assembly: visual poems of the Italian Futurists at the Getty. Note this, this (English version), this, and this (English version). You should be able to download those . . .

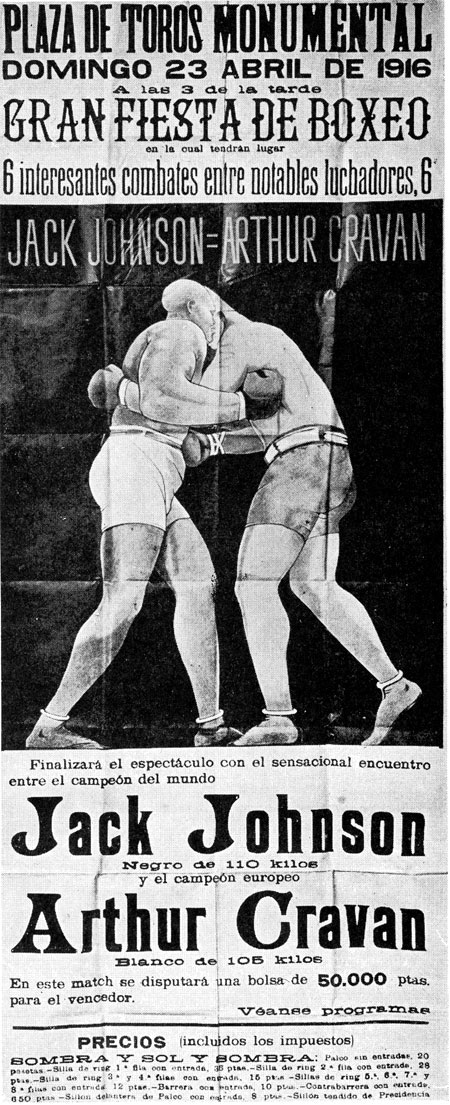

“. . . . Soon you won’t see anyone but artists in the street and the one thing you’ll have no end of trouble in finding is a man. They are everywhere: the cafés are full of them, new art schools open up every single day. I’ve always wondered how a teacher of painting, unless he teaches a locksmith how to copy keys, has ever been able to find a single pupil since the beginning of the world. People make fun of those who frequent palm-readers and other fortune tellers and never indulge in any irony about the simple souls who go to art school. Can anyone learn to draw or paint, to have talent or genius? And yet we find in these studios big dadoes of thirty or even forty and God forgive me, ninnies of fifty, yes, sweet Jesus! poor old fogies of fifty . . . .

It may be argued that art schools provide painters with heat in winter and a model. And for a true painter a model is life itself. At any rater you can judge for yourself whether a professional model is more alive than the plaster statues people copy in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts; but the frequenters of the Academie Matisse are full of contempt for the pompous deadheads at the Beaux-Arts; why, just imagine: they are turning out advanced art. It is true that some among them believe that art is superior to nature. Yes, my dear!

I am astonished that some crook has not had the idea of opening a writing school.”

(Arthur Cravan, “Exhibition at the Independents” (1914). Reprinted in Robert Motherwell’s The Dada Painters & Poets: An Anthology, p. 4. Translated by Motherwell, I assume.)

(Umberto Boccioni, Visioni simultanee, 1911. Oil on canvas, 60.5 x 69.5 cm. Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal.)

“It is the architectonic gesture of the Virgin which accomplishes the miracle, as she pulls at her mantle with her left hand so as to enclose herself in an absolute pyramid which turns, an unmoved mover, on a crystalline pivot, until is establishes before us the ideal axis which, etched in the fold on the forehead, runs down the protruding part of the face and descends past the closed edge of the drapery as far as the jutting corner of the pre-Dieu. But the right hand advances at an angle, to test cautiously the possible boundary of the pictorial space; having found it, it halts; while, counterbalancing it, the book slices the air with the sharp blade of its bright page. In the hollow within the column of the neck, there slowly settles the enclosed ovoid of the face, over which turn, as over a planet, broad diagrams of regular shadows.”

(Roberto Longhi, from “Piero dei Franceschi e la pittura veneziana”, quoted (and translated) by David Tabbat in his introduction to Three Studies, pp. xiii–xiv)

(Giorgio Morandi, Still Life (The Blue Vase), 1920. Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf.)

“As for Morandi, he has never been a metaphysical painter. The limit was reached when the prize for metaphysical painting was given unanimously, but probably through the insistence of the modernistologist Professors Roberto Longhi and Lionello Venturi, to their beloved Morandi. Now you, dear reader, if you want to realise the mentality and morality prevailing today in certain circles of modern art and modern culture, think on this fact: an official exhibition, organised in Italy with money from Italian taxpayers, includes the paintings of a very well-known Italian painter without even inviting him and without even informing him, going against all rules of good behaviour and all usual morality. This very well-known Italian painter, who has created a style or a genre, if you wish, of painting, a style or genre which belongs to him and only to him, is exhibited along with works of other painters described arbitrarily and tendentiously as metaphysical, one of whom, as I have said, did no more than plagiarise, while the other has nothing whatever to do with metaphysical painting. Then to cap everything a money prize was even instituted, this prize being given to the man whose paintings had nothing whatever to do with the metaphysical style. Think about it hard,, dear reader, and you will find it impossible to imagine anything more improper and shameless.”

(The Memoirs of Giorgio de Chirico, trans. Margaret Crosland, p. 186.)