Continuing to live – that is, repeat

A habit formed to get necessaries –

Is nearly always losing, or going without.

It varies.

This loss of interest, hair, and enterprise –

Ah, if the game were poker, yes,

You might discard them, draw a full house!

But it’s chess.

And once you have walked the length of your mind, what

You command is clear as a lading-list.

Anything else must not, for you, be thought

To exist.

And what’s the profit? Only that, in time,

We half-identify the blind impress

All our behavings bear, may trace it home.

But to confess,

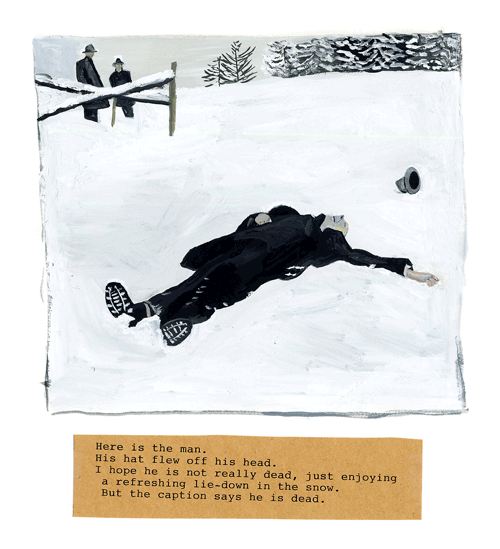

On that green evening when our death begins,

Just what it was, is hardly satisfying,

Since it applied only to one man once,

And that one dying.

(Philip Larkin)