Eleanor Antin

Eleanor Antin

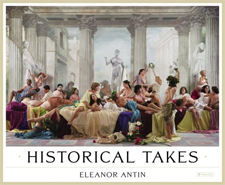

Historical Takes

(Prestel, 2008)

I first ran into Eleanor Antin’s work in the Pompidou a few years ago; they were showing an edition of her 100 Boots, which immediately clicked with me: conceptual art that was immediately funny but not stupid, a tricky area to work. She’s someone who pops up in New York with some regularity: Carving was part of the “Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution” show at PS1; her video of herself as The King was at MoMA. I found this book on winter sale in the gift shop at MoMA as well, where I was hoping to find postcards from the Bauhaus show; it’s a catalogue of a show at San Diego Museum of Art a few years back of her stagings (not quite restagings) of classical scenes in the foothills of Southern California. (I don’t know if Francesco Vezzoli’s Caligula is likely to hold up as well as Antin’s The Death of Petronius (2007) as a representation of the last decade’s excesses.) There’s a good interview with her by Max Kozloff and a pair of contextualizing essays by Betti-Sue Hertz and Amelia G. Jones.

But mostly this book is about the photographs. They’re not quite as immediate as 100 Boots, as one can’t look at these photographs without knowing there’s a subtext that needs to be unpacked. Antin’s playing with representations of women, obviously; scenes of Roman decadence set in what’s obviously southern California carry a weight now that might not have been foreseen when the book was published, presumably the middle of 2008 when the exhibition started. Antin’s also engaging with digital manipulation: the frontispiece, Constructing Helen (from Helen’s Odyssey), 2007, shows men sculpting a body several times their size, the body of a woman made to look like she’s made of marble. Not all are as blatant in their manipulation of photographs, but how the conventions of art is clearly a major subject: models posed as they would be in an Alma-Tadema or Poussin look astonishingly fake. Animals prove endearingly unwilling to be posed.

The strongest sequence (and the most remarked upon in the book’s text) is Helen’s Odyssey, a recasting of her story. The centerpiece is two versions of Judgment of Paris (after Rubens): Paris chooses between a bandoliered Athena with an automatic rifle, a vamping Aphrodite, and a 1950s housewife Hera, all posed before a painted backdrop that wouldn’t be out of place in an Italian restaurant. Helen, at the margins of the painting, looks directly at the viewer; going back to Rubens, we find that she’s not there at all.

The King of Solana Beach makes a welcome but short appearance at the end of the book, as do photographs from Angel of Mercy and part of Recollections of My Life with Diaghilev 1919–1929 by Eleanora Antinova, an alter ego. They’re fantastic short narratives; one wishes for a collected edition of Antin’s work. I can’t find fault with this book, though; it’s beautifully produced, and being too short isn’t the worst crime. I’d love to see the actual photographs.