Kristin Hersh

Kristin Hersh

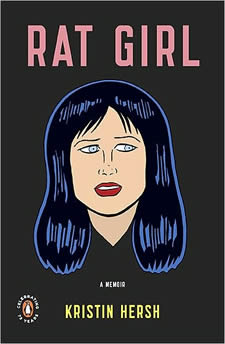

Rat Girl: A Memoir

(Penguin, 2010)

The first time I would have heard Kristin Hersh’s music would have been sitting in a station wagon in a dark parking lot somewhere in rural Illinois waiting to pick someone up. Occasionally in the car you could pick up the modern rock stations from Chicago, and what they played was more interesting that the omnipresent classic rock stations, with their monotonous diet of Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Bad Company, Rush, occasionally mixed in with whatever new music might be masculine enough to fit in (Candlebox, maybe Pearl Jam). NPR was occasionally interesting, but not predictable; all in all, it was a frustrating state to be in when it was clear from whatever media did seep in that things were happening elsewhere, happening without you. It’s a state that wouldn’t exist a year later, when I went east to college & the Internet came along; but that’s how things were in 1994, near the end of something though I didn’t know it at the time. That was the environment in which I first heard Throwing Muses’ “Bright Yellow Gun,” the single off University: the song and then the record sounded like a transmission from another world. Faux-surrealism was stock in trade for rock lyrics at that point in time; but Kristin Hersh sounded more like she meant it than most: there was an awkwardness that wasn’t contrived, and the imagery couldn’t easily be resolved into standard adolescent concerns: something else seemed like it was happening.

Early artistic impressions can be hard to shake off; most of what one accords value when young is embarrassing in hindsight, especially when growing up in an environment of cultural deprivation. Throwing Muses were, as it turned out, one of the first bands I saw after arriving at college, a free show on the Esplanade in Boston in front of a crowd of drunken fratboys who clearly didn’t like them, validation in my eyes. It was easy, around that time if you were a certain sort of young person concerned with pop music, to get bogged down in Baudrillard and interminable arguments about fake authenticity; but Throwing Muses seemed to somehow be outside that argument.

Writing about pop music is almost invariably awful, and this is only intended as background to my reading of this book. I don’t love memoirs; it’s a form that too often lends itself bad writing because of too easy recourse to the truth: the truth about most people’s lives is not art, even if it may be diverting. The rock memoir promises to be the worst of all possible books. But there are exceptions; and this might be one of them. Rat Girl is a memoir of Hersh’s 18th year, when her band was playing regularly in Providence and Boston, when she was ostensibly attending college, when she was diagnosed as being bipolar, when her band was signed to a British record label and recorded its first album, and when she unexpectedly wound up pregnant. What I like here is how much is left unexplained: the overtly Freudian title, an epithet that Hersh uses to describe herself throughout the book; how the members of the band appear to be living as homeless while Hersh seems to maintain a reasonably close relationship with her parents; how she came to be friends with Betty Hutton; how she came to have a baby in the first place. All the obvious questions that a journalist would like answered about Hersh’s early life are entirely disregarded in this book.

What remains is a record of experience; a note at the front explains that it’s based on a diary of the year, but nothing of that diary remains, and it’s difficult to imagine what might be in it. Hersh and her band seem to live like savages or baby rabbits, crashing in abandoned apartments, falling asleep whenever they stop moving, using a language that seems to be their own. There’s a strangeness here that can’t quite be classified. A sequence early in the book between Hersh and her drummer, who’s just brought in some trash to use as percussion:

Sitting up to admire his garbage, I notice that he’s wearing a coat. I’m stunned. “Dave . . . what the hell?”

Dave and I always believed that coats were for wimps who couldn’t handle seasons: “coat slaves.” Geez, people, get a grip! Seasons happen! And that vision was for wusses: people who couldn’t hack the rough-hewn, fuzzy life we lived – slaves to their glasses – when we could play entire shows without seeing anything. It was the only thing we were smug about, really, our ability to live blind and cold.

Then, a few months ago, he showed up at our attic practice space wearing glasses. I felt betrayed, but he was transformed. “Trees have individual leaves, even when they’re far away!” he insisted, his eyes and new lenses shining. (p. 62)

This isn’t the only point in this book where one thinks of Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. What’s most interesting is Hersh’s relationship with her songs: something that started, she says, when she briefly lived in an apartment she calls the Doghouse:

. . . by the time I raced out the door . . . it was too late. I was branded; tattooed all over with Doghouse songs – each one a musical picture etched into my skin.

I know that when my band plays these ugly tattoos, people can see them all over me, but I don’t care too much. I mean, shy people are generally not show-offs, but the burning that the songs do, the fact that I’m compelled to play them, makes me think they . . . matter? Maybe that’s not the right word. That they’re vital. And I respect that. I can feel sorry for myself without judging the music. (p. 12)

This is also a memoir of mental illness: hit by a driver while on a bicycle when young, Hersh’s songwriting seems to be related to her bipolarity:

A few days later, lying in my hospital bed, I heard my first song: a metallic whining, like industrial noise, and a wash of ocean waves, layered with humming tones and wind chimes. Intermittent voices talked and sang. I thought it was the TV in the next room. The TV never shut up, though; nobody ever turned it off or even changed the channel. I started to worry that the patient next door had died or slipped into a coma. (p. 76)

Hersh doesn’t valorize her bipolarity as the source of her creativity; it’s simply something that’s there that has to be lived with, much the same attitude she has later when she discovers that she’s pregnant:

I really didn’t mind getting hit by a car, though – it was interesting, and probably my last chance to fly through the air in nonjudgmental fashion. I think if I got hit by a car now, it’d bug me, but before we learn to by whiny about our existence and how comfortable it isn’t, we’re still open to being thrown around, even if we bust our faces when we land. So what if sudden contact with the street makes your teeth fall out, maybe snaps off a foot or two? At least you know what that feels like. (p. 78)

There’s something very likable about this book: it’s not for everyone, and certainly my relation to it is going to be charged by personal experience. But it’s far more interesting than writing about music, than a memoir should be.