W. N. P. Barbellion

W. N. P. Barbellion

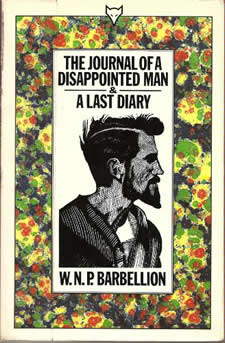

The Journal of a Disappointed Man & A Last Diary

(The Hogarth Press, 1984; originally 1919)

W. N. P. Barbellion was the pen-name of Bruce Cummings, a British entomologist who died of multiple sclerosis at the age of 30 in 1919. “Barbellion” he chose because it sounded grandiose; “W. N. P.” stood for “Wilhelm Nero Pilate.” His complete works can be found in very readable format at Ray Davis’s pseudopodium.org; best-known is The Journal of a Disappointed Man, packaged here with a sequel, A Last Diary. Barbellion has fallen into the public domain; there are innumerable shoddy print-on-demand editions of his work on Amazon; but the one I read was properly printed by the Hogarth Press in 1984; it includes a useful biographical introduction by Deborah Singmaster, though it doesn’t include his older brother’s useful preface to A Last Diary. I don’t know anything about the Hogarth Press in post-Woolfian incarnations, but they did publish the copy of Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve in English that I have, also from 1984, titled By Way of Sainte-Beuve, in the same format as this one. I find it odd that it’s so hard to find a copy of that book by Proust in English; but I’m inclined to look warmly on anyone who’s publishing it. Looking online, it seems like Chatto & Windus bought Hogarth in 1946; Random House UK bought out Chatto & Windus in 1987, which might be why both of these books seem to languish in publishing limbo at the moment. There seem to have been a few editions of his work since 1984, but they’re hard to find. A second collection, Enjoying Life and Other Literary Remains seems to be even more vanishing.

The Journal of a Disappointed Man is composed of edited extracts of Cummings’s journal, starting when he was thirteen (when he reports that he has “abandoned the idea of writing on ‘How Cats Spend their Time’”) and ends in October of 1917, when he was twenty-eight; the final sentence in that book, seemingly intended to be facetious, declares that “Barbellion died on December 31,” although actually Cummings lived until June of 1919. The Journal records his life, first as he struggles to educate himself enough to become a zoologist, eventually ending up with a mostly thankless job as an entomologist at the Natural History Museum in Kensington. Barbellion has never been in the best health, however; his health worsens as the book continues. In a moment of respite he marries and has a child; his interests turn increasingly to music and literature, and the journal (in its edited form) becomes increasingly a creative rather than a documentary project: in February 1916, for example, he is reading the Goncourts’ Journal. His illness is diagnosed as what would come to be called multiple sclerosis, but the fact is hidden from him; he discovers that before his marriage, his family took his wife-to-be aside and informed her of this.

The Journal of a Disappointed Man is thus something of a familiar form: the record of a man who knows he must die trying to find the most honorable way to prepare himself. This might lend itself to the bathetic; but Barbellion’s work mostly escapes this, perhaps because of the time it was written in: after Darwin (and perhaps Thomas Hardy, who can be felt her), religion has been tossed out as a method for understanding the world. Barbellion’s approach to his predicament has an almost clinical feel, as this excerpt from an entry from January 20, 1917 suggests:

I am over 6 feet high and as thin as a skeleton; every bone in my body, even the neck vertebræ, creak at odd intervals when I move. So that I am not only a skeleton but a badly articulated one to boot. If to this is coupled the fact of the creeping paralysis, you have the complete horror. Even as I sit and write, millions of bacteria are gnawing away at my precious spinal cord, and if you put your ear to my back the sound of the gnawing I dare say could be heard. (p. 274)

Although it’s a powerful image, bacteria don’t actually eat the spine in multiple sclerosis; perhaps that was a valid theory at the time. Despite this jaundiced view – and perhaps patches of depression, though the conscious editing makes it hard to tell – Barbellion takes life as it is and enjoys it: disease is a part of the natural world. The progress of the disease lends an inexorable narrative arc to the book – a possible treatment is mentioned a single time, but there’s a war on & it’s clear that it’s going to be terminal. This progression is modulated by the inclusion of A Last Diary, which stretches from March 1918 to June 1919: this book actually was published posthumously, and it records the progress of the Journal (being championed by H. G. Wells) through the presses. The Diary serves to give something of a happy ending to Barbellion’s story: while the disease grows ever more agonizing, the success of the Journal will allow him to provide for his widow and child, and his literary endeavors have been appreciated.

For its subject, Barbellion’s work isn’t as dark as it might be: the naturalist’s curiosity never leaves him, even though he eventually tires of the institutional structures in which he is made to work. The penultimate entry in A Last Diary captures this:

Rupert Brooke said the brightest thing in the world was a leaf with the sun shining on it. God pity his ignorance! The brightest thing in the world is a Ctenophor in a glass jar standing in the sun. This is a bit of a secret, for no one knows about it save only the naturalist. I had a new sponge the other day and it smelt of the sea till I had soaked it. But what a vista that smell opened up!—rock pools, gobies, blennies, anemones (crassicorn, dahlia—oh! I forget). And at the end of my little excursion into memory I came upon the morning when I put some sanded, opaque bits of jelly, lying on the rim of the sea into a glass collecting jar, and to my amazement and delight they turned into Ctenophors – alive, swimming, and iridescent! You must imagine a tiny soap bubble about the size of a filbert with four series of plates or combs arranged regularly on the soap bubble from its north to its south pole, and flashing spasmodically in unison as they beat the water. (pp. 382–3)

I don’t think Stanley Elkin, a very different writer who also suffered from multiple sclerosis, ever wrote about Barbellion’s work; I hope I’m wrong.