Frederic Tuten

Frederic Tuten

Tintin in the New World: A Romance

(Inprint Editions, 2005; original, 1993)

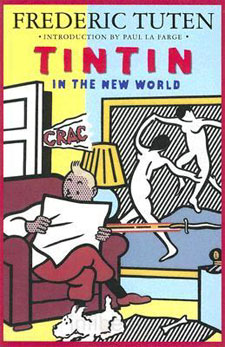

This is not a book that is well-served by the Internet. The Amazon reviews are almost unanimously damning; a LibraryThing one suggests that this is “Maybe the worst book ever written.” This is not the worst book ever written. It is a well-connected book: on the back cover, there are blurbs from Jonathan Coe, Susan Sontag, Larry McMurtry, and Leslie Marmon Silko. The copyright page explains that the Roy Lichtenstein cover was “created expressly for this novel”; another Lichtenstein drawing of the same subject serves as a frontispiece. The book is dedicated to “my friend George Remi (Hergé) and Roy Lichtenstein”. The novelist’s friendship with Hergé (real or metaphorical, I don’t know) is almost certainly what causes the online reviewer’s bad reactions: this is a book that takes Hergé’s characters and puts them into another context, along with a lot of characters from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. This is a fine conceit for a novel in the pop art tradition; however, it’s a formula that’s going to leave Internet browsers who assume this is a Tintin spinoff deeply unhappy. I picked my copy up at 192 Books: its presence there made it clear that it’s a certain type of book – more so because this copy was signed, implying that Frederic Tuten is the sort of author who reads at 192 Books. I picked it up because I knew that Tuten was associated with Donald Barthelme andFiction back at that journal’s beginnings, rather than because Tintin was in it (though Tintin, of course, doesn’t hurt); he’d been on my list of people to get around to reading for a while. But that sort of paratextual context tends to get lost on the Internet. This is, among other things, a book about Tintin, and that seems to be how the Internet insists on reading it.

But this book. Tintin, at Marlinspike with Captain Haddock and Snowy, is at loose ends; he wants something to involve him. A letter from Brussels, one presumes from Hergé, summons Tintin to Peru where an adventure should happen. No adventure happens. Instead, Tintin promptly meets the secondary characters from The Magic Mountain: Peeperkorn, Settembrini, Naphta (whose name has become “Naptha,” perhaps so that it’s not pronounced “NAFTA,” or perhaps to suggest naupathia), and Clavdia Chauchat. Tintin becomes Hans Castorp; Captain Haddock mostly fades away, a drunk resigned to his fate. Snowy is philosophical and doesn’t assume that anyone will understand him since he lost the power of language early in the Tintin series. Tintin finds love with Clavdia; eventually, he does in Peeperkorn. The complementary Settembrini & Naptha end up as lovers. Tintin finally leaves the mountain to become a savior to the natives.

Mixing and matching characters from earlier books has become commonplace in the past decade, whether in fan fiction on the Internet or in the bookstores with Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters. It’s hard to remember how radical this would have seemed even in 1993; this book follows hard in the tradition of Barthelme, both in his love of the readymade and in his strategy of setting up a ridiculous situation and then scrutinizing how it might play itself out. When this works well – as in, for example, Snow White – the fictional and the mundane cross paths: Snow White and the seven dwarves’ dilemmas are our dilemmas. One doesn’t, perhaps, learn very much about the original narrative – except how strange it actually is – but the present is illuminated.

That’s what’s happening here, mostly. Tintin’s life doesn’t make a great deal of sense when scrutinized closely: ostensibly he is a reporter, but he never appears to do any actual reporting. Tintin is perpetually youthful; he lives in Marlinspike with Captain Haddock, a violent drunk. Tintin’s life isn’t quite as endlessly recurring as, for example, The Simpsons, as his adventures do have a direction, but it doesn’t seem that Tintin ever really learns anything. He has adventures, over and over again, with beginnings, middles, and ends. He’s a character, and he lives through stories. The way a plot works isn’t the way life works: what Tuten does in this book is to take the character of Tintin and drop him into a world that’s marginally more realistic. Tintin finds love with Clavdia, and begins, instantly, to age: towards the end of the novel he has “man-sized hands” and possibly a beard. There’s an echo here of Shakespeare’s Prince Hal narrative, with Haddock taking on the character of Falstaff, wanting to rage on forever, though I don’t think this is a case of Hal being right and Falstaff being wrong: Snowy, Tintin’s conscience, goes home to Marlinspike with Captain Haddock.

The broader question here is why we read what we read. Plenty of the same people who read Tintin read The Magic Mountain; but they read them for vastly different reasons. This is why, I think, a distinction can be drawn between something like this and Sense and Sensiblity with Sea Monsters: that book exists as a novelty, a reification of the idea “wouldn’t this book be more entertaining if there were sea monsters in this book”. Austen’s premises are immaterial: her book is raw material for comedy. There’s a comic element to Tuten’s novel, but it’s not a hilarious book; rather, it’s a serious attempt to see what happens when the two books are put together. Tintin is the reader’s dream of eternal youth; The Magic Mountain is a negation of the possibility of that dream in the real world. There’s validity in both, but they don’t sit comfortably together as each looks ridiculous in the light of the other. Tintin’s existence seems weirdly retarded; the Magic Mountain seems overwhelmingly somber. In a scene towards the end of the book, Peeperkorn, having taken up painting, shows Tintin how he has imposed Clavdia’s figure on the entire history of Western art, from Leonardo to Ruscha: he constructs his own narratives. Tintin never quite manages this; adrift in the end, wanders off into another another narrative entirely, becoming, perhaps the one that the Incas describe as the messiah to come.

Did I like this book? I didn’t love it in the way that I love the Barthelme pieces that do the same things: I can’t find the hilarity or the depth of feeling that I do in those works. This is a book that’s happy to be unsure of genre and for that reason it’s hard to judge – perhaps this is why the reviews on Amazon and LibraryThing are so savage. But it’s an engaging book: it’s been kicking around my head for a while, and I’m not sure that I’m done with it yet.

Pingback: february 6–february 10 « with hidden noise

Thank you for your fair minded words. I have never written in answer to those who have written absurd things, inventions, about the book or to those who have never read the novel but sagely add further negative comments.

In any case, I’m glad you read the book and I send you all my best wishes.

By the way, Paul La Farge has written a very fine,illuminating essay about the novel which may be found on line and which is the preface to the most recent edition of the book published by Imprint Editions.

Pingback: Reviews: Tintin in the New World: A Romance by Frederic Tuten | LibraryThing