Alvin Levin

Alvin Levin

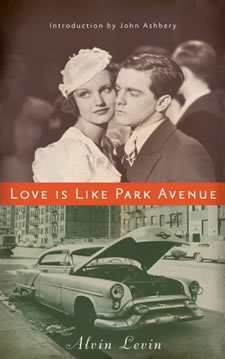

Love Is like Park Avenue

(ed. James Reidel)

(New Directions, 2009)

Love Is like Park Avenue collects the fiction of Alvin Levin, who was born in 1916, but seems to have given up writing fiction in 1943: seven years worth of writing, mainly short pieces, make up his entire literary output, not quite breaking 200 pages. The title, which appeared on two distinct pieces collected here, was to have been that of Levin’s novel, which never materialized; it’s hard to tell, from the content here, what form that novel would have taken, as Levin doesn’t seem to have been given to conventional unities of plot or character. The editor suggests that much of this material might have been part of a novel; but Levin has been dead since 1981, and his rumored novel was nowhere to be found in his possessions.

Levin, born in Paterson, New Jersey, grew up in the Bronx and attended City College; most, though not all, of his work seems to center around lower-middle class Jews in roughly similar situations. In his introduction, James Reidel notes that Levin had polio and walked with a crutch for most of his life; Reidel suggests that Levin lived vicariously through his younger sister, both in his life and in his fiction. (“A Cool Drink Is Refreshing,” written in 1939, might be the most straightforwardly autobiographical work here: the story is told from the perspective of a young woman who visits a boys’ school to tell her brother that their father has found him a job, delivering milk; the implication is that he’ll need to quit school.) It’s hard to tell how much to read into this: but Levin does have a pronounced sense of empathy, and he captures his women characters, narrators as often as not, remarkably well. Following the examples of Faulkner and Dos Passos, Levin generally uses a stream of consciousness narration; the point of view frequently shifts, and the narrator at the end of a piece (“story” seems the wrong word) often isn’t the one who started it. Names and locations sometimes shift capriciously; this seems to be intentional. His prose is always energetic: Levin is always an interested observer even if his exact position can be difficult to pin-point. The excerpt from a novel published in 1942 as “Love Is Like Park Avenue” is composed of a series of short vignettes, none longer than a few pages, each with different characters; there’s a unity to the world and vision that Levin presents, but the characters, their voices, and their situations are constantly shifting

Having grown up in the Depression, Levin’s subject is frequently the lower classes; but he never writes as a tourist, seeking to explain how the other half lives to an educated audience; nor is his writing polemical. There’s no disdain in his words; what he sees in life, and he puts it down on paper with the hope, perhaps, that someone will read it. It’s possible that this comes through most clearly because Alvin Levin was never actually a successful writer, though William Maxwell asked him to submit material to the New Yorker and the British poet Nicholas Moore asked him for a story for an anthology of avant-garde fiction. This doesn’t seem like writing for a mass audience or for an avant-garde audience; Levin appears to have been interested primarily in pleasing himself, a supposition that might be entertained because he seems to have voluntarily given up writing entirely. In Reidel’s telling, this seems to have been because he had many other interests keeping him busy: he was a lawyer, and seems to have run a successful pamphlet-publishing business for years.

Reading Levin now, one notices the kinds of fiction that we don’t have today. The contemporary American novel, or that subset of it known as literary fiction, is generally written by the upper class because it is written for the upper class. The social structures that generate fiction and its writers – MFA programs – are, with a few notable exceptions, self-selecting, limited to those who don’t need to make a living. It’s not an accident that the New Yorker, the most prominent venue where new fiction might be seen, is aimed squarely at those who aspire to be upper class. This isn’t something unknown – Walter Benn Michaels was making this argument a few years ago, albeit hamfistedly – but it’s generally not discussed, as class doesn’t tend to be discussed in America. This isn’t solely a contemporary problem – writing itself has always tended to limit itself to those who have the time and leisure to engage in it – but Levin’s book suggests that things have not always been quite so stagnant as they are now. Writing, for Levin, seems to have been a possible agent of social mobility, an aspirational vehicle: the upper classes wrote, but he could write too; by doing so, he could earn the prestige of a millionaire like James Laughlin, who corresponds with him like a peer. But avant-garde writing isn’t a viable way out of the lower middle class, especially if you need to support yourself because you’ve been crippled by polio; Levin might have realized this, and this might be why he turned away from writing. It’s hard to blame him, but it’s our loss.

It’s worth noting that this is an unusually attractive book for New Directions, whose recent work has been deeply disappointing given the publisher’s long history of good book design. Levin sought to be published by James Laughlin; his most prominent publications were in New Directions annuals, but James Laughlin never seems to have coaxed the promised novel out of him. James Reidel arranges his work chronologically, interspersing correspondence to and from potential publishers; useful notes complete the volume, and John Ashbery’s brief preface recalls how exiting his voice was in 1942 and explains his part in Levin’s republication. We’re lucky that Levin found the young Ashbery as a reader.

Pingback: Reviews: Love Is Like Park Avenue (New Directions Paperbook) by Alvin Levin | LibraryThing

Pingback: august 2–august 10 « with hidden noise