Michael Allen Zell

Michael Allen Zell

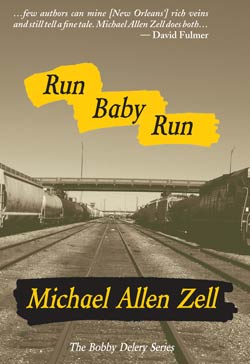

Run Baby Run

(Lavender Ink, 2015)

The trajectory of Michael Allen Zell’s career is an interesting one; three books in, it’s still not clear what to make of him. I enjoyed 2012’s Errara, a short, sharp reworking of Bruno Schulz and Cabrera Infante set in New Orleans that might have been something the Dalkey Archive published in the 1990s. It was a happy surprise when his followup, The Oblivion Atlas, turned up in the mail here; while one might have expected a more conventionally sized novel as a followup. Zell confounded with a collaboration with News Orleans artists Louviere + Vanessa, who have provided book design and illustration to a book of short stories. That book might be seen as a reworking of Georges Rodenbach’s 1892 Bruges-la-Morte transposed to New Orleans.

Like Rodenbach’s illustrated book, The Oblivion Atlas was hard to classify, falling somewhere between Wisconsin Death Trip and Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife: the illustrations and design were integral to the reading experience; like in Gass’s book (and Errata), this was a major subject. The first story, “Port Saints,” reflects usefully on the place of reading and writing today: the narrator, Benjamin Sender, describes a bookshop where the books are stacked in helices; the shopper who pulls out a book risks causing a disaster. This might serve as an oblique commentary on the endlessly proliferating “ten bookstores you have to see” slideshows on the Internet: there’s a fetishization of the object of the book, though one wonders if looking at bookstores is too often a substitute for the act of reading itself. Everyone likes the idea of books (and the idea of writing books); but a decorative book functions differently than a read book. The proprietor makes this understood:

. . . each time the proprietor calmly stating the same gentlemanly good-bye he imparted to me many times, Remember, like Faulkner said, Nobody down here has time for reading because they’re all too busy writing. (p. 14)

The Faulkner quote is from an exchange with students at the University of Virginia in 1958:

Q: Why are you not as well read in the South as in the North?

A: Everyone in the South has no time for reading because they are all too busy writing. (M. Thomas Inge, ed., Conversations with William Faulkner, p. 167.)

When said by a writer, this is a petty complaint, or an attempt to get a laugh. When said by a bookseller, it’s something different. (We learn in the author’s note for Run Baby Run that Zell has “worked as a bookseller since 2001,” which isn’t particularly surprising.) And placed in Zell’s book, it seems significant: these are readerly books, books made from a lifetime of reading for an audience who will appreciate that. This isn’t to say that they’re academic or especially formal at all: they’re not. Rather, they’re books for a small audience.

At the same time, another thread through his books cuts against their readerliness: their determined engagement with the city of New Orleans. New Orleans is never far from the surface in Zell’s books; and that continues with Run Baby Run, which might otherwise be seen as a wild swerve in Zell’s writing. Run Baby Run is crime fiction: it’s obviously the same writer (there is a scene in this one where the protagonist has a pure moment of happiness visiting a bookstore, a moment that promises a future), but it’s consciously aimed at a different sort of audience than Zell’s previous two books. Zell’s avant-garde antecedents aren’t displayed as prominently as in his previous books, though that influence is still there: if ever there was a Schulzian detective story, it’s this one.

But what Zell has set himself to this time is not just a difference in audience, it’s a difference in focus. Zell isn’t only interested in the problems of the artist: he’s also interested in the world and how one must live in it, especially in a world as radically broken as the present moment. (Not being in New Orleans, I haven’t seen any of Zell’s theatrical work, though I suspect it might be a connecting link between his focuses on the reader and the world.) The avant garde isn’t always especially helpful in that regard: the characters populating Run Baby Run are by and large not readers (which is true of most Americans, of course). This doesn’t make Zell less interested in them, though it’s abundantly clear which side he’s on. But his interest now is trying to make sense of a broken world, and fiction’s capacity for empathy is important.

Run Baby Run is a short crime novel; the cover proclaims it part of “The Bobby Delery Series,” which suggests that this is a prelude to more. Bobby Delery is a criminologist from Chicago who returns to New Orleans; for reasons that aren’t clear, he’s asked to join the New Orleans police in an investigation into the unreported theft of a club’s unreported profits. The police, it is clear from the beginning, are corrupt; a world of other criminals circle the theft. Zell’s narration moves easily from person to person; and it becomes clear that he’s interested in how different people lead wildly different lives in post-Katrina New Orleans. There are points of light, in this book at least: in the day that we are with Delery, he appears to be spotless, and a couple of other people come off as well. Some groups (the attendants of a black church) come across better than others (drunken out-of-town partiers). One imagines that this will not continue to be the case with Delery: there are hints of a past that’s not quite finished with him left hanging. The book’s shortness is frustrating: one can imagine more to come.

Zell’s used his shift in genre to start thinking seriously about race in America, and about how it plays out in New Orleans. It’s an important subject and a fine setting; again, it’s a relief to me to see someone putting out serious American fiction that’s not set in the gentrified parts of New York. I can’t say how accurately he portrays the city, though it comes off as real, as do most of his characters and their voices. There’s a similarity to Sergio de la Pava’s A Naked Singularity, if not quite in form at least in strategy; as ever, I’m interested to see where he goes.