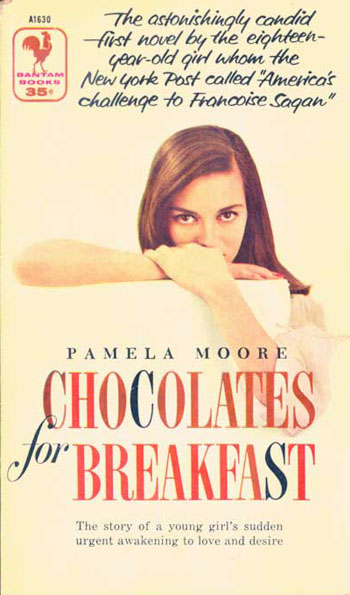

Pamela Moore

Pamela Moore

Chocolates for Breakfast

(Bantam Books, 1957; originally 1956)

It’s strange that I’ve never really written about this book, as it’s one that I’ve foisted on many people over the years. The occasion of my latest re-reading is that it’s finally been reprinted, by Harper Perennial; you can learn a great deal more at Kevin Kanarek’s site here.

I found this book through Robert Nedelkoff’s examination of Moore’s career in The Baffler in 1997; it was only after I arrived in New York in 2001 that I managed to turn up a copy. Why this book struck me then, in retrospect, seems clear: the vision of youth that it presented was so markedly in contrast to the mawkishly sentimental view of childhood then coming into vogue in, for example, the early McSweeney’s aesthetic and the films of Wes Anderson after Rushmore. There was a rampant refusal to grow up, an idealization of childhood: J. D. Salinger and his cloyingly precocious protagonists bear no small amount of responsibility (as might, at a remove, the conservatism of Brideshead Revisited). To me at the time this felt wrong-headed; and it was refreshing to find a bildungsroman in which a sixteen-year-old so actively decides to be an adult. It’s not a book that could have been written in 2001, though it’s a book I needed to read then.

Perhaps because the author was so young when she wrote this, the book can be convincingly serious. But this is done in a controlled way: while the book is generally told from Courtney Farrell’s perspective, there’s a clear distance between the author and the narrator, and perspective shifts even inside paragraphs. There’s also a fine control of the structure: between chapters 12 and 13, we learn that Courtney’s spent two months in a sanitarium, though we’re never really given an explanation of what triggered this (chapter 12 closes with a description of Courtney cutting her fingers to feel something, though it’s clearly not a suicide attempt) or what might have happened there. It’s glossed over quickly – in almost a deadpan way – and the narrative moves on; it’s left to the reader to remember that this happens and might (or might not) illuminate her subsequent behavior.

A willingness to take on ambiguity gives this book power. There’s an early scene where Courtney’s advisor Miss Rosen has given her Finnegans Wake (“How are you coming with James Joyce?” “Not awfully well. What is he trying to say with all this stream-of-consciousness gibberish?”). Miss Rosen, who clearly has a crush on the girl, explains the book allegorically, as if Joyce were writing self-help:

“What he is talking about in Finnegans Wake,” explained the English teacher in her precise, analytical manner, “is the eternal conflict between parents and children. He presents the parent as the figure who must be conquered if the child is to gain independence and identity.”

“How simply and clearly she puts it,” Courtney thought as Miss Rosen went on, quoting from the book and analyzing the selections to prove her thesis, “when the subject is so terribly complex. Teachers are a little like scientists in their way of breaking down the magnificent vastness of life into small particles that can be analyzed, and thereby robbing it of its emotion.” She remembered the scene when her mother had said she could not spend that weekend with her father because she had to much schoolwork to do. . . . (p. 7)

Moore clearly knows this is funny: her intercutting Miss Rosen’s dogged explanations (cribbed, it eventually becomes clear, from Campbell & Robinson’s Skeleton Key, which she offers as an aid) with scenes from Courtney’s family life goes on for several pages. While Miss Rosen’s exegesis might be correct in a general way, she’s missing, as Courtney realizes, anything that’s interesting about Joyce; and no silver bullet is going to solve Courtney’s problems.

There’s an interesting reversal of this scene later in the book: the sybarite Anthony Neville, who does manage to become her lover, tells her an allegorical story to explain the magnificent vastness of his lonely, and lost, childhood to her. She questions him:

“Didn’t he go back to look for it?”

“No, of course not,” Anthony said crossly. “If you must know, he called into the cave, but there wasn’t any answer, so he simply walked wretchedly back to his villa and had a Brandy Alexander.”

“He never found it again,” Courtney said despondently.

“No,” said Anthony gravely. “It was lost for good.”

“What a sad story. What’s the moral?”

“Now, the moral is obvious, angel, and if you’re so think you can’t see it, I refuse to explain it to you. Did you like the story?” (p. 120)

With Anthony, Courtney is happy; but it’s a respite from the world that doesn’t last. If there’s a problem with this book, it’s the speed of the denouement: her old roommate Janet kills herself, and Courtney decides that it’s better to stick to the straight and narrow path, ending up with an unappealing, if honest, suitor who’s been to Harvard Law and has little time for the carousing set she’s spent much of the novel with. Anthony is cast to the side, and their romance fizzles out, rather than inevitably crashing and burning, as the reader expects. Again, it’s a calculated choice that Courtney makes: but at this point the reader knows her well enough to understand that this kind of analytical thinking won’t last or make her happy; nor can it be done under emotional duress.

Moore wasn’t entirely pleased with this version of the book; the French and Italian versions worked from another version of the text, and Kevin Kanarek’s essay in the new edition of this book suggests that it’s difficult to know what Moore would have done given more time and less editorial intervention. Even so, it remains a fine novel and it deserves more attention. And for as serious as the book is, there are as many scenes of pure pleasure:

“Maid’s out,” Janet observed. “She’s always going out on obscure errands. I think she has a lover.”

“The elevator man?” Courtney inquired.

“Probably someone’s butler. That sounds logical. A somewhat indigent butler, who works for an alcoholic couple. The son is dying of leukemia, and the parents are always in the bedroom, bombed. And the butler slips out, abandoning the dying son, to make made love with Peggy under the El.”

“Under the El.” Courtney thought a moment. “The rhythm of the trains makes them mad, like Spanish fly or something. And it’s all like a Bellows painting.”

“Who?”

“Bellows.”

“Oh. And then the son dies,” Janet continued, “but nobody knows it for weeks because the parents are out of their head and the butler has taken Peggy to Coney Island in the heat of passion.”

“Finally a window washer sees the body and it’s all in the Daily News,” said Courtney.

“You want ice, don’t you?” asked Janet.

“Mmmm-hmmm. I’ll get the Scotch.” (p. 98)