- Scottish indie label Chemikal Underground present Ballads of the Book, a collection with lyrics by Scottish poets, including Alasdair Gray (who also provides the artwork) & Edwin Morgan.

- Late notice: there’s a Circumference-sponsored reading of Slovenian poetry tonight at Columbia. Slovenian and American poets Aleš Debeljak, Brain Henry, Tomaž Šalamun, and Andrew Zawacki will read their poetry and discuss translation. Tuesday 6 March, 7:30 pm, Columbia University School of the Arts, 2960 Broadway at 116th St, Dodge Hall, Room 413.

- Also: there’s a Circumference 5 launch reading in Amherst this Sunday. Jonathan Bolton reads Czech, Elliott Colla reads Arabic, Krista Ingebretson reads Spanish, and Dara Wier reads some of her homophonic translations. Sunday 11 March, 3 pm, Jones Library, 43 Amity St, 3rd floor, Amherst, Massachusetts.

- Scanned issues of German magazine Simplicissimus (1896–1944) in PDF format, noted here.

a blessing in disguise

Yes, they are alive and can have those colors,

But I, in my soul, am alive too.

I feel I must sing and dance, to tell

Of this in a way, that knowing you may be drawn to me.

And I sing amid despair and isolation

Of the chance to know you, to sing of me

Which are you. You see,

You hold me up to the light in a way

I should never have expected, or suspected, perhaps

Because you always tell me I am you,

And right. The great spruces loom.

I am yours to die with, to desire.

I cannot ever think of me, I desire you

For a room in which the chairs ever

Have their backs turned to the light

Inflicted on the stone and paths, the real trees

That seem to shine at me through a lattice toward you.

If the wild light of this January day is true

I pledge me to be truthful unto you

Whom I cannot ever stop remembering.

Remembering to forgive. Remember to pass beyond you into the day

On the wings of the secret you will never know.

Taking me from myself, in the path

Which the pastel girth of the day has assigned to me.

I prefer “you” in the plural, I want “you”

You must come to me, all golden and place

Like the dew and the air.

And then I start getting this feeling of exaltation.

(John Ashbery, from Rivers and Mountains, 1967. Recording from 1966 here from Giorno Poetry Systems’s Biting off the Tongue of a Corpse, 1975.)

the incredulity of st. thomas

learning to see

“In addition to the traditional piano player, each theatre in Saragossa was equipped with its explicador, or narrator, who stood next to the screen and ‘explained’ the action to the audience. ‘Count Hugo sees his wife go by on the arm of another man,’ he would declaim. ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, you will see how he opens the drawer of his desk and takes out a revolver to assassinate his unfaithful wife!’

It’s hard to imagine today, but when the cinema was in its infancy, it was such a new and unusual narrative form that most spectators had difficulty understanding what was happening. Now we’re so used to film language, to the elements of montage, to both simultaneous and successive action, to flashbacks, that our comprehension is automatic; but in the early years, the public had a hard time deciphering this new pictorial grammar. They needed an explicador to guide them from scene to scene.

I’ll never forget, for example, everyone’s terror when we saw our first zoom. There on the screen was a head coming closer and closer, growing larger and larger. We simply couldn’t understand that the camera was moving nearer to the head, or that because of trick photography (as in Méliès’s films), the head only appeared to grow larger. All we saw was a head coming toward us, swelling hideously out of all proportion. Like Saint Thomas the Apostle, we believed in the reality of what we saw.”

(Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh, trans. Abigail Israel, p. 32–33.)

on transience

“My conversation with the poet took place in the summer before the war. A year later the war broke out and robbed the world of its beauties. It destroyed not only the beauty of the countrysides through which it passed and the works of art which it met with on its path but it also shattered our pride in the achievements of our civilization, our admiration for many philosophers and artists and our hopes of a final triumph over the differences between nations and races. It tarnished the lofty impartiality of our science, it revealed our instincts in all their nakedness and let loose the evil spirits within us which we thought had been tamed for ever by centuries of continuous education by the noblest minds. It made our country small again and made the rest of the world far remote. It robbed us of very much that we had loved, and showed us how ephemeral were many things that we had regarded as changeless.

We cannot be surprised that our libido, thus bereft of so many of its objects, has clung with all the greater intensity to what is left to us, that our love of our country, our affection for those nearest us and our pride in what is common to us have suddenly grown stronger. But have those other possessions, which we have now lost, really ceased to have any worth for us because they have proved so perishable and so unresistant? To many of us this seems to be, but once more wrongly, in my view. I believe that those who think thus, and seem ready to make a permanent renunciation because what was precious has proved not to be lasting, are simply in a state of morning for what is lost. Mourning, as we know, however painful it may be, comes to a spontaneous end. When it has renounced everything that has been lost, then it has consumed itself, and our libido is once more free (in so far as we are still young and active) to replace the lost objects by fresh ones equally or still more precious. It is to be hoped that the same will be true of the losses caused by this war. When once the mourning is over, it will be found that our high opinion of the riches of civilization has lost nothing from our discovery of their fragility. We shall build up again all that war has destroyed, and perhaps on firmer ground and more lastingly than before.”

(Sigmund Freud, “On Transience”, first published 1916, pp. 178–179 in Writings on Art and Literature, trans. James Strachey.)

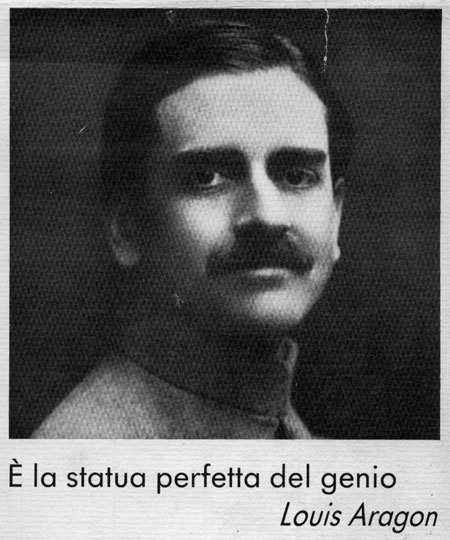

è la statua perfetta del genio

to another city

“The impulse that made him travel to another city and lead a completely isolated existence, free of family ties or distractions of any kind, also seems to have made him want to preserve that experience, intact and inviolate, for himself alone. He hinted at this in a late filmed interview with the French documentary filmmaker Jean-Marie Drot. ‘In 1912 it was a decision for being alone and not knowing where I was going,’ Duchamp said. ‘The artist should be alone . . . Everyone for himself, as in a shipwreck.’ ”

(Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp, p. 93.)

are you ticklish?

We’re leaving again of our own volition

for bogus-patterned plains, shreds of maps recurring

like waves on a beach, each unimaginable

and likely to go on being so.

But sometimes they get, you know, confused

and change their vows or the ground rules

that sustain all of us. It’s cheery, then, to reflect on the past

and what it brought us. To take stone books down

from the shelf. It is good, in fact,

to let the present pass without commentary

for what it says about the future.

There was nothing carnal in the way omens became portents.

Fact: all my appetites are friendly. I just

don’t want to live according to the next guy’s trespass,

meanwhile getting a few beefs off my chest,

if that’s OK. The wraparound flux we intuit

as time has other claims on our inventiveness.

A lot of retail figures in it. One’s daily horoscope

comes in eggshell, eggplant, and, just for the heck of it,

black. ’Nuf said. The deal is off. The rest is silence.

(John Ashbery)

book design

the more loving one

Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.

Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total darkness sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.

(W. H. Auden, 1957)