Frederic Tuten

Frederic Tuten

The Adventures of Mao on the Long March

(New Directions, 2005; originally 1971)

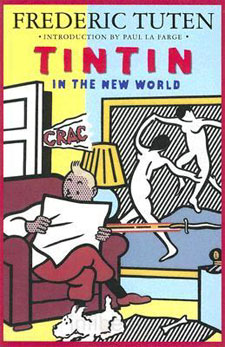

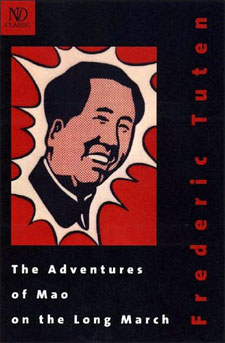

The Adventures of Mao on the Long March is a collage-novel which tells, in circuitous fashion, what happened on Mao’s Long March. Although they initially appear to be the same, Tuten’s Long March firmly diverges from Mao’s Long March. The novel ends with an interview with Mao in 1968; in a description of Mao’s apartment, we learn that he reads, among many other periodicals, Artforum, Esquire, The Nation, and Cahier du Cinéma, and we realize that we are in the company of a different Mao. Before the interview, there are sections from a realist history of the Long March, collaged texts usually about aesthetics, sections of invented dialogue and action, and sections which parody the style of American writers. This is a book that reads very differently than it did when first published, in part because it has gained a great deal of front and back matter. Starting at the front of the book, one finds a forward written in 1997 by the author; then an introduction, John Updike’s “Satire without Serifs” (originally a review published in the New Yorker); then the book itself; then a list of sources used in the book (when this was added is unclear); and finally a postscript written in 2005 by the author, which goes some way into describing the book’s history. The cover, a lithograph of Mao by Roy Lichtenstein, also needs to be read as part of the book, as it was created for the original text.

But this is also a book that can be read differently when you burrow down to the text itself. Composed in part of sections borrowed from other texts, it was initially published without a list of sources; some the reader would be likely to recognize (bits of Hawthorne, Pater, and Wilde, for example), some less susceptible to recognition (long extracts from James Fenimore Cooper’s Venetian novel The Bravo). Now, of course, it’s very easy to tell where his sources spring from: plugging a string of text into Google generally brings even the unfamiliar to light. The first paragraph, for example, I found weirdly familiar; sending the phrase “to wit, a bottle of strawberry syrup” to Google provides two results, the first being this book and the second being the August 1898 issue of The Quartier Latin (the quoted text is the paragraph beginning “A beauty show” and ending “and so there was peace and happiness”), which I’m fairly certain I’ve never read. (This source, for what it’s worth, isn’t listed in the list of sources; an epigraph from Antony and Cleopatra is, but that epigraph isn’t to be found in my copy. Maybe it fell out of the book in some reprinting.) Before Google, most readers would have had to let this quote pass by; now anyone can pretend erudition.

I’m sent back to Guy Davenport’s essay on Barthelme’s “Paraguay,” “Style as Protagonist in Donald Barthelme,” in which he carefully folds back the story to find the unacknowledged sources (a travelogue by Jane E. Duncan and Corbusier) to see how they resonate:

Barthelme’s genius was in such layering. Sometimes we can locate all the layers, sometimes not; Barthelme clearly wanted us to remain in the interstices: that’s where his poetry is. He does not mind (in fact, has alerted us) that phrases like “vast blind wall” and “vast expanse of blankness” can be identified as prose by an architect who cannot control the echoes these phrases contain from Kafka, Mandelstam, Piranesi, and from history. (p. 109 in The Hunter Gracchus.)

“Paraguay” appeared in 1969, slightly before The Adventures of Mao on the Long March; but there’s a similar aesthetic strategy being used, one found as well in the contemporaneous collage essays of Paul Metcalf. Tuten, like Metcalf, is essentially using language as a readymade; this goes for both the found texts on aesthetics, as well as for the parodies of the style of American authors, where an existing style is also something that can be taken and used as a tool. I think of the story of when Duchamp and Brancusi visited an airshow; pointing to a propellor, a beautiful example of industrial design, Duchamp said “Painting’s washed up. Who’ll do anything better than that propellor? Tell me, can you do that?” There are already so many things in the world: direct creation counts for less in such a world. The same goes for plot: Mao’s Long March was, as the real Mao realized, something that could be used as a metaphor; Tuten appropriates it for his own use. Tuten differs from Metcalf in that Metcalf’s interests (at least after Genoa) are not fiction, but rather describing a subject through juxtaposition.

Although this is a comic novel which uses parody as an essential rhetorical stategy, Tuten doesn’t seem to be making fun of the original texts, even though it might be very easy to do so; rather, he allows them to shine under a different light to show what else might be there. An early section, for example, lifts a visit to the sculptor Kenyon’s studio in Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun:

“Here might be witnessed the process of actually chiselling the marble, with which (as it is not quite satisfactory to think) a sculptor in these days has very little to do. In Italy, there is a class of men whose merely mechanical skill is perhaps more exquisite than was possessed by the ancient artificers, who wrought out the designs of Praxiteles; or, very possibly, by Praxiteles himself. Whatever of illusive representation can be effected in marble, they are capable of achieving, if the object be before their eyes. The sculptor has but to present these men with a plaster-cast of his design, and a sufficient block of marble, and tell them that the figure is imbedded in the stone, and must be freed from its encumbering superfluities; and, in due time, without the necessity of his touching the work with his own finger, he will see before him the statue that is to make him renowned. His creative power has wrought it with a word. (pp. 8–9.)

How sculpture was thought of in 1970 was worlds away from how Hawthorne imagined sculpture in 1860; Tuten’s genius is to see that Hawthorne’s words could be recast to describe what had happened in the visual arts in the twentieth century and what Tuten was attempting to bring to the world of fiction. The author of the collage novel is, to a certain extent, putting himself in the same position as the reader: in his introduction, Tuten notes that he wrote this book while working on a Ph.D. on Cooper, and one doubts that anyone not reading Cooper in that fashion would have found the sections of The Bravo that Tuten finds to use. Like the reader, the author makes sense of these juxtapositions.

It seems important that Mao was still alive when this book was written (and when Lichtenstein’s print was made), as opposed to Warhol and DeLillo’s use of him: dead, he existed only as icon. Appropriating a living person as a character is a braver act (with the caveat, of course, that Mao was presumably then, as now, so distant as to be unreal). Written now, this book would register has historical fiction; in 1971, Mao’s legacy had not entirely congealed and could, one presumes, still be shaped. Lichtenstein’s Mao is a jolly Mao; in the 2005 afterward, Tuten recalls getting a telegram from a confused Diana Vreeland congratulating him on his scoop in interviewing Mao. At that point in time, Mao could still be shaped.

This is a well-wrought book, one which should be discussed more than it is. It’s odd that this book hasn’t come up recently in relation to David Shields’s Reality Hunger: it’s a fine example of how collage can be used inside the structures of fiction rather than precluding fiction, as Shields seems to be arguing.