Florine Stettheimer

Florine Stettheimer

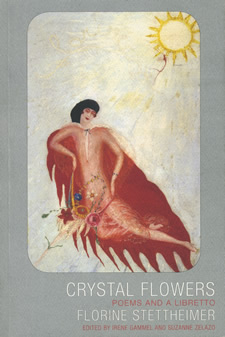

Crystal Flowers: Poems and a Libretto

(edited by Irene Gammel & Suzanne Zelazo)

(BookThug, 2010)

This is a bit unexpected: an edition of the poetry of Florine Stettheimer, best known as a painter, from BookThug, a Canadian press new to me. Over the summer I read her sister Ettie’s novel and became aware of Florine’s poetry, a first published after her death by Ettie in 1949 in a compilation called Crystal Flowers. This turns out to have been impossible to get ahold of because it was published in an edition of 250. This edition, new in November, presents those poems, three additional ones, and the libretto for a ballet; it also wraps them in a fantastic editorial apparatus, with a lengthy introduction, extensive textual notes, a glossary of abbreviations and allusions, and a chronology of her life. Perhaps Florine Stettheimer still isn’t tremendously appealing to the masses: this new version exists, says a note on the text, in an edition of 500, a number that’s painfully small (and perhaps why this isn’t being published by an academic press). But even though not many people will see it, this is still a tremendously useful book, and it deserves some attention.

Florine might be the best-documented of the Stettheimer sisters: it turns out that there are a couple of biographies of her, most recently that of Barbara J. Bloemink in 1995, coinciding with a retrospective at the Whitney, but also one from 1963 by Parker Tyler, whose Divine Comedy of Pavel Tchelitchew still sits mostly unread on my shelves. Irene Gammel, one of the editors of this book, wrote a biography of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven which I’m always meaning to pick up. This discussion of biography aside, this book is particularly useful because it’s an edition of Florine’s poetry: and while it is well supplemented by biographical elements, this is, first and foremost, a volume of poetry which can finally be read as such.

Gammel and Zelazo’s edition of Crystal Flowers follows Ettie Stettheimer’s original arrangement of the poem, adding three uncollected pieces at the beginning and adding a short ballet libretto at the end. The poems are grouped into thematic sections: “Nursery Rhymes,” “Nature/Flora/Fauna,” “Things,” “Comestibles,” “Americana,” “Moods,” “People,” “Notes to Friends,” and finally “As Tho’ from a Diary,” a sequence of autobiographical poems. Sequence is important here: the initial poems seem to be self-consciously doggerel in the style of Edward Lear. The first untitled poem:

My neighbor

The Cat

Sat

On a mat

Her mouth

Like a trap

With eyes

That snap

She smiles

At a Rat

And now

She is fat

That’s

That!

This isn’t the most auspicious beginning; and one wonders if Florine Stettheimer would have wanted this published at all, though it seems like the sort of thing that might have been sent to friends: perhaps Ettie’s edition of 250 was as intended as a keepsake rather than a literary production. Turning to the notes, however, we learn that “My neighbor” was Ettie’s emendation for Florine’s original “My daughter-in-law”, which creates a poem of entirely different feeling. There’s no obvious biographical antecedent to take away the strangeness: Carrie, Florine, and Ettie lived with their mother until her death and never married – although their often forgotten older siblings, Frank and Stella, did leave the maternal fold and marry. Gammel and Zelazo’s introduction suggests that comparison might be made to Emily Dickinson; this might be stretching it, but after the run of nursery rhymes, the poetry opens up and becomes more interesting. There’s the suggestion of the influence of H.D.’s imagism in her nature poems, like this tiny one:

Today

The breaking waves

Look like

Ruffled-edge petunia leaves

The poems are unfortunately not dated; it’s hard to tell when they would have been written, and though the Stettheimers would probably have been in the same social circles as William Carlos Williams and Mina Loy, it’s hard to say what Florine would have been reading. The easy sense of rhyme remains a constant through most of her poetry: these aren’t the most rigorous poems, though they’re not as unthinking as the first section might suggest. With “Things” and “Comestibles” the poems become decidedly strange, as the narrator inhabits other consciousnesses and uses riddle-like forms. Here, she becomes a canvas:

I was pure white

You made a painted show-thing of me

You called me the real-thing

Your creation

No setting was too good for me

Silver – even gold

I needed gorgeous surroundings

You then sold me to another man

This isn’t quite as tight as it might be – the third line doesn’t quite work – but there’s still a kick to the last line, forcing the reader to go back. Stettheimer was fond of the second person, which blooms in the “Comestibles” section, where she imagines herself to be various types of food:

You stirred me

You made me giddy

Then you poured oil on my stirred self

I’m mayonnaise

Here one does think of Dickinson: this is undeniably a good poem, and it’s hard to think of anything quite like its terse application of a cheerfully insane metaphor to personal relations. Again the last line kicks, almost anticlimactically in its simple declaration; but it doesn’t solve a riddle so much as start asking questions. This approach isn’t always the one she takes: some of these poems are simply about food, seemingly without a personal component. She starts a poem from the perspective of a pig (“You called me hog”) though her perspective shifts and she seems to end empathizing with a piece of ham: “You changed me completely / Even my name / You called me Ham”. What matters here isn’t that the ham was once part of a pig; it’s the ham’s status as an object, something that can be held in thrall by naming.

The final sections of poems, “People” and “Notes to Friends,” might have the most immediate interest: the Stettheimers inhabited an artistic sphere, and many of their friends turn up here: Carl Van Vechten, Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Demuth, Gertrude Stein, Marcel Duchamp. The editors’ notes are useful here, pointing out who people referred to by first names and initials are likely to be. The notes don’t take up the temptation to overstretch themselves, however. “A relatively long poem that begins “We Flirted” is left opaque: it tells of a transatlantic flirtation carried out over time, until the narrator says:

“Let’s celebrate

This faithful

long flirtation

give a fête

invite many

They shall give us

Crystal things

Diamonds

Venetian glass

Perhaps

we could accept

Sapphires

Perhaps

we could build

a treasure house

all of glass.”

His glasses

strangely

dulled

his eyes

They became

an opaque barrier

on which

Our flirtation

Shattered

In a thousand

Splinters.

There’s a temptation to read this as being about Marcel Duchamp, who arranged for a retrospective of Florine Stettheimer’s work at the Museum of Modern Art soon after her death. Duchamp, though he led a transatlantic existence, doesn’t seem to have worn glasses while Florine was still alive: but like her, he was very taken with the idea of glass: “a treasure house / all of glass” could describe either of their work.