Herman Melville

Redburn: His First Voyage

(originally 1849)

It’s been a long time since I read this book, back in college; I remembered it as a mostly ineffectual warm-up for Moby-Dick, not as interesting as Typee or Omoo or as bizarre as Mardi, published the same year, even if Melville’s prose was maturing; it’s the subject matter that isn’t as interesting. A young fancy lad (Wellingborough Redburn) of a noble family brought low resolves to go to see to make his fortune; the sailors make fun of him (not least by constantly calling him “Buttons”), he wanders around Liverpool, the city of his misguided dreams, and he returns to America, sadder and slightly wiser. It’s a sea story clearly written for a perceived public appetite for the same (it did better than Mardi did); it’s a bildungsroman that takes wild detours in the same way that Melville will try a few years later with the wonderfully deranged Pierre. It is hard to imagine that Redburn is anyone’s favorite Melville, though Wikipedia assures me that it was John Masefield’s.

I came back to it mostly because I was interested in one particular aspect of it: after arriving in Liverpool after a narrative in which Redburn apparently is tricked out of or manages to lose everything he had at the start and seems to have nothing but the ridiculous clothes on his back, we’re suddenly told that he brought with him a particularly prized possession, his late father’s copy of an old guidebook to Liverpool. At the start of the book, he found a ship going to Liverpool from New York; but no particular reason is given for this choice, though it has been mentioned as a place his father visited, though there is presented alongside Le Havre and London. This is one of the points in the text that make it seem like Melville is heading towards Moby-Dick: he pretty clearly gets bored with he set out to do, and tries doing something else for a while, though maybe he shouldn’t have been so clearly writing the book in a strictly linear fashion.

This book is a mess in no small part because it’s shaped as a novel. The guidebook section is more or less self-contained; after it happens, it’s not mentioned again, even for several more chapters where Redburn traipses around Liverpool describing the sights, having seemingly forgotten about his guidebook. There are a handful of other similarly self-contained episodes that make up the plot of this book: Reburn wanders New York, destitute; Redburn has a bad time sailing to Liverpool; the guidebook segment; Redburn mostly happily wandering around Liverpool; Redburn encounters abject poverty; the hitherto friendless Redburn suddenly makes a friend and is taken on a strange tour of what seems to be the gay underworld; Redburn (and friend) sail back to New York, with vignettes describing the horrors of the treatment of emigrants onboard. The voyage out is taken up by sailors making fun of Redburn; on the voyage back, Redburn is as invisible as Ishmael, and we have no idea what his relations with the sailors might be. Redburn’s friend, Harry Bolton, is made fun of by the sailors; they arrive in New York, and Redburn abandons him to go back to his family. Bolton, he finds out afterwards, ended up on a whaling ship and was smashed between a whale and a ship. Tricked by the captain, Redburn ends up more indigent than when he started out. What, if anything, has been gained in return?

Perhaps it is knowledge of the world; maybe it is the loss of youthful illusions. In the novel’s final chapter, we learn that Redburn learns of Bolton’s fate much later, when he himself was on a whaling ship, previously described as one of the worst fates imaginable; and later than that, presumably, he becomes the narrator of the book, though nothing in the narrative suggests this as a possibility – aside from, perhaps, the guidebook episode, chapter XXX, “Redburn Grows Intolerably Flat and Stupid over Some Outlandish Old Guide-Books”. Back in Chapter III, we were told how (seemingly randomly) he embarked on a ship to Liverpool; in Chapter XXX, after a long, Moby-Dick-ish bibliography – Redburn’s father also went to Paris, Rome, and Cambridge, all of which seem more obviously romantic than Liverpool – we get this which poses the later Redburn in his childhood library:

And lastly, and to the purpose, there was a volume called “THE PICTURE OF LIVERPOOL.”

It was a curious and remarkable book; and from the many fond associations connected with it, I should like to immortalize it, if I could.

But let me get it down from its shrine, and paint it, if I may, from the life.

The book is valuable to Redburn as a memento of his father, Walter Redburn, who inscribed it in 1808; the book has his notes, as well as drawings that Redburn himself added in his childhood, when he evidently read this book dreaming of Liverpool. Walter Redburn’s notes put him at particular points in the city at particular points in time, returning the dead father to life. The book, it is worth pointing out, is a real one, a version of which can be seen here, and looking through that it seems as if Melville was padding his text by describing and quoting from the real book with no appreciable differences. Quoting becomes vertiginous here: at a certain point in the “Survey of the Town” (page 33 in the edition above), the guidebook quotes (for nine pages!) an anonymous poem, as Melville notes:

And the anonymous author must have been not only a scholar and a gentleman, but a man of gentle disinterestedness, combined with true city patriotism; for in his “Survey of the Town” are nine thickly printed pages of a neglected poem by a neglected Liverpool poet.

By way of apologizing for what might seem an obtrusion upon the public of so long an episode, he courteously and feelingly introduces it by saying, that “the poem has now for several years been scarce, and is at present but little known; and hence a very small portion of it will no doubt be highly acceptable to the cultivated reader; especially as this noble epic is written with great felicity of expression and the sweetest delicacy of feeling.“

Books are of course made from books, often by people in libraries. Where things get interesting is the next chapter, where the young Redburn, having managed to bring this book to Liverpool with him, attempts to use it to come to know the town:

On the passage out I studied its pages a good deal. In the first place, I grounded myself thoroughly in the history and antiquities of the town, as set forth in the chapter I intended to quote. Then I mastered the columns of statistics, touching the advance of population; and pored over them, as I used to do over my multiplication-table. For I was determined to make the whole subject my own; and not be content with a mere smattering of the thing, as is too much the custom with most students of guide-books. Then I perused one by one the elaborate descriptions of public edifices, and scrupulously compared the text with the corresponding engraving, to see whether they corroborated each other. For be it known that, including the map, there were no less than seventeen plates in the work. And by often examining them, I had so impressed every column and cornice in my mind, that I had no doubt of recognizing the originals in a moment.

In short, when I considered that my own father had used this very guide-book, and that thereby it had been thoroughly tested, and its fidelity proved beyond a peradventure; I could not but think that I was building myself up in an unerring knowledge of Liverpool; especially as I had familiarized myself with the map, and could turn sharp corners on it, with marvelous confidence and celerity.

This, of course, is delusion:

It never occurred to my boyish thoughts, that though a guide-book, fifty years old, might have done good service in its day, yet it would prove but a miserable cicerone to a modern. I little imagined that the Liverpool my father saw, was another Liverpool from that to which I, his son Wellingborough was sailing. No; these things never obtruded; so accustomed had I been to associate my old morocco guide-book with the town it described, that the bare thought of there being any discrepancy, never entered my mind.

What was the town’s fort is now a tavern; the hotel where his father had stayed no longer exists. The book, he finds, is “no more fit to guide me about the town, than the map of Pompeii”. He lets his rhetoric get carried away:

Here, now, oh, Wellingborough, thought I, learn a lesson, and never forget it. This world, my boy, is a moving world; its Riddough’s Hotels are forever being pulled down; it never stands still; and its sands are forever shifting. This very harbor of Liverpool is gradually filling up, they say; and who knows what your son (if you ever have one) may behold, when he comes to visit Liverpool, as long after you as you come after his grandfather. And, Wellingborough, as your father’s guidebook is no guide for you, neither would yours (could you afford to buy a modern one to-day) be a true guide to those who come after you. Guide-books, Wellingborough, are the least reliable books in all literature; and nearly all literature, in one sense, is made up of guide-books. Old ones tell us the ways our fathers went, through the thoroughfares and courts of old; but how few of those former places can their posterity trace, amid avenues of modern erections; to how few is the old guide-book now a clew! Every age makes its own guidebooks, and the old ones are used for waste paper. But there is one Holy Guide-Book, Wellingborough, that will never lead you astray, if you but follow it aright; and some noble monuments that remain, though the pyramids crumble.

It’s not quite clear which version of Redburn is meant to be saying this – it sounds like the younger Redburn who has just learned a life-lesson, though the ridiculous overblown ending points to the nihilism found in Pierre, a whole book about the untrustworthiness of dead fathers. Less orotund a bit later:

But, Wellingborough, I remonstrated with myself, you are only in Liverpool; the old monuments lie to the north, south, east, and west of you; you are but a sailor-boy, and you can not expect to be a great tourist, and visit the antiquities, in that preposterous shooting-jacket of yours. Indeed, you can not, my boy.

True, true—that’s it. I am not the traveler my father was. I am only a common-carrier across the Atlantic.

Melville might be describing his own book here: he knew it was bad, though there are parts of it (this and the Harry Bolton narrative) which point to something more interesting to come. It’s odd that he should be so forthright. At least the book sold?

Eugene Burdick and William Lederer

Eugene Burdick and William Lederer  Dexter Palmer

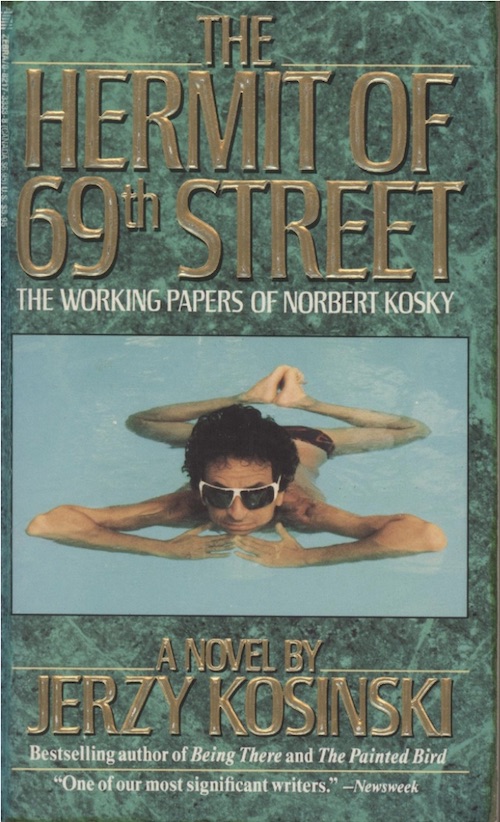

Dexter Palmer  Jerzy Kosiński

Jerzy Kosiński