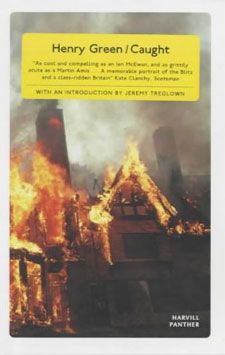

Henry Green

Henry Green

Concluding

(Dalkey Archive; originally 1948)

It’s hard not to tear through the last Henry Green novel I have left, Concluding. Still on the shelf is Surviving, the volume of odds and ends put together by Matthew Yorke. I am glad I went through Caught and Back before Concluding: this book is not so consumed with World War II. Rather, it’s class that concerns Green; this is a usual subject for him, though here it appears in a different sense entirely that what might be expected. No two novels by Green that are entirely similar – Nothing and Doting, maybe, though I’m not sure how well that holds up – but this might be the oddest of them. Maybe this is why I like Green so much: after eight novels, he still surprises.

The plot takes place over a day; the previous night, two girls disappear from a girl’s school. The two administrators of the school, Miss Edge and Miss Baker, are more concerned with scheming on how to get an elderly scientist, Mr. Rock, to leave his house on their grounds; Mr. Rock does not want to leave, as he lives happily with his cat, goose, and pig, named Alice, Ted, and Daisy, respectively, as well as his granddaughter, Elizabeth, who is recovering from a nervous breakdown. At the school, a dance, for Founder’s Day, is to happen that night.

This is a lighter book than Back and Caught, almost pastoral, though this is a pastoral distinctly tinged with shadow. The image of dappled sunlight and shadow is one that comes up repeatedly here; this happens down to the level of the book’s sinuous sentences, which often start in one place and end some place else altogether. Here, Miss Marchbanks, interim administrator, considers what to do:

Extremely short-sighted, she had taken off her spectacles and put these on Miss Edge’s desk as though, in the crisis, at a time when she had been left in charge, she wished to look inwards, to draw on hid reserves, and thus to meet the drain on her resolution which the absence of the girls had opened like an ulcer high under the ribs, where it fluttered, a blood stained dove with tearing claws. (p. 39)

Or this love scene:

“Adams won’t like this,” she said, and turned with a smile which was for him alone to let him take her, and helped his heart find hers by fastening her mouth on his as though she were an octopus that had lost it’s arms to the propellers of a tug, and had only its mouth now with which, in a world of the hunted, to hang onto wrecked spars. (p. 46)

Immediately after this, one of the missing girls is found; but we never entirely learn what happened to her. Nor are her superiors in a hurry to find out.

There is something odd about this book. One notices first that Miss Edge tends to capitalize many of her nouns. At first one assumes this is cod-Victorian emphasis, though one wouldn’t expect that in a book by Green; likewise, the girls of the school all have names starting with “M,” which might be a stylistic choice to show off how interchangeable the girls seem to be. But as the book progresses, it becomes clear that the world that this book takes place in might not be a realistic portrait of Britain in the late 1940s, as one might have assumed from Green’s other books. Halfway through the book, letters arrive for Edge and Baker from a state functionary, directing them that a change has been decided upon, and the girls are to be trained to be professional pig farmers, because there is not enough opportunity for the girls in the “State Service”. We seem to be in a socialist Britain, albeit one that still has a queen. Going back to the beginning, the book reads differently; it becomes strange. We find Mr. Rock explaining to Adams how he got his cottage: “Why, when the State took over from the owner, and founded this Institute to train State Servants, it was even in the Directive that I was to stay in my little place” (p. 7). This doesn’t particularly stick out the first time through: all institutional language is affected and mildly ridiculous.

But here is the reason that Edge and Baker aren’t particularly interested in the girl’s disappearances: it will mean an agony of reports. Elizabeth explains to Mr. Rock, her grandfather, how things are, with particular reference to her lover, one of the girls’ teachers:

“You see, when you’re young and all that,” she went on, “starting in the State Service, because I know, Gapa, I’ve done it, things have so changed since your day, well then, then slightest bad report he gets and he’ll never receive promotion. Never. It isn’t a story, honest. No redress, nothing. And you realise what an Enquiry means, if you appeal against one of these awful Reports. It’s the end. Absolutely. Even if you think you’ve brought it back, it boomerangs back onto you. (p. 143)

An explanation for the other girl’s continued disappearance becomes apparent: Mary was orderly to Edge and Baker and was worn out from working, so she’s run away from the Institute. The delusional Edge considers this possibility and dismisses it:

Because they all knew that attendance on Baker and herself was an honour for which every one of the girls longed, it was just the little extra to be intimately close to them both. Nevertheless, she saw how the whole thing could be made to look if Mary did not come back soon, how black if this latest fantastic story was allowed to creep around. (p. 131)

Another explanation becomes apparent later: the girls, it turns, might not be as innocent (or as interchangeable) as they might appear. But, as the title suggests, nothing is ever concluded.

It’s not entirely surprising that this should turn out to be speculative fiction – the book did appear in the window between Animal Farm and 1984, and one might assume that something was in the air in Britain after the war – but it’s a surprise to be getting this from Green. The politics aren’t particularly surprising: Green never tries to disguise the fact that he was upper class, despite his empathy for the lower classes. It might make sense that this is the book Green wrote after Back; following this, he turned (self-consciously, presumably) to the upper-class trifles of Doting and Nothing, a turn that might be seen as a retreat if those books weren’t so good in their own rights.