John Crowley

John Crowley

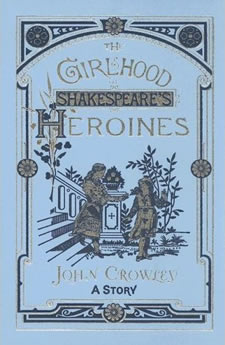

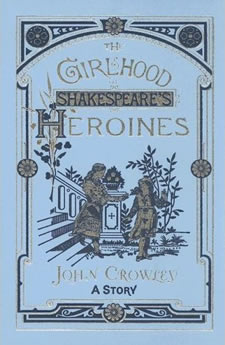

The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines: A Story

(Subterranean Press, 2005)

So I am slowly working my way through the back catalogue of John Crowley, and having read most of the major things, now I’m mopping up the rest. This is a short book, barely a novella; the text was originally published in Conjunctions 39, but this is a beautiful edition from the Subterranean Press, hard cover with a silver-foil stamped boards: it’s hard to resist picking up such a book, and I generally don’t. In Amherst for a few days, I bought too many books; this is the one I turned to first, though there are others I should be reading.

I like John Crowley’s work in part because it’s not quite clear how to pigeonhole him. Most obviously, a case could be made that Little, Big and the Ægypt books are fantasy, but an equally strong argument could be made for the opposite. This is usually discussed whenever Crowley’s work is discussed; maybe it accounts for his odd place in the literary firmament. In this book, another of Crowley’s characteristic traits appears: it’s nostalgia-inflected and there’s a layer of sentimentality, something that can also be found in the bigger books. Sentimentality, of course, is generally banished from serious literature as the enemy of rigorous thought. Crowley here (and elsewhere) seems to be deploying it as a tool in his arsenal: it’s an odd trick, with interesting results.

The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines starts out apparently as a nostalgia trip: recalling a fictitious Indiana Shakespeare Festival from the late 1950s when the narrator would have been in high school. Doing the math reveals that the narrator’s age would seem to be approximately the same as Crowley’s; but put that aside. The narrator is a young Shakespeare enthusiast; he is clearly going to fall for Harriet, another young Shakespeare enthusiast whose youth is also described. Things risk becoming precious: the narrator is a dreamer who gets the idea from library books that he would be able to create a Greek theater in his backyard. Fourteen pages in, however, we are jerked into the present moment: Harriet is 38, the year is apparently 1981, as a Bulgarian has attempted to assassinate the Pope. Harriet and the narrator are not, apparently, together. Harriet is a photographer, and the description of her method suggests that something else is going on:

But these photographs don’t disappoint that way. The happiness they give is a little pale and fleeting – half an hour to set up the camera and make an exposure (hurry, hurry, the earth’s turning, the light’s changing) and an hour or two to make a true print: but it’s real happiness. Since they’re made from paper negatives rather than film, they seem to Harriet not to have that look of being stolen from the world rather than made from it that most landscape photographs have; they are shyer and more tentative somehow. Not painting, no, but satisfying in some of the same ways. (p. 16)

This comes after a discussion of the disappointment of painting: Harriet painted what she saw, but the next day found the resulting paintings not to accurately reflect the world. But there’s a lot buried here: this consideration of how art fits into the world doesn’t mesh with the youthful idealization of Shakespeare-as-great-artist in the previous section. Something has happened, it’s clear; and we’re sent back to the Indiana Shakespeare Festival, where blooming young love pushes the middle-aged present of the protagonists to the background again.

Complication sets in with the arrival of a man, nameless, who delivers a lecture to the young Shakespeareans on how Shakespeare could not have written his plays; he suspects that Francis Bacon is the likeliest candidate. The speech goes on in detail: it seems to be an introduction of doubt. Young love blossoms; the bookish young narrator goes to the library and discovers the voluminous works of those who have doubted Shakespeare’s authority, starting with Delia Bacon and continuing through to the present. And then the book changes entirely: as the summer winds on, the narrator and Harriet are separately stricken with polio. The pastoral beginning can be read very differently, as the narrator sees the braces of the Baconian speaker from the present:

I’ve thought of those canes, since then, and those braces. I’ve wished I could ask about them. There are things in your past, preserved in memory almost by chance, that only later on, because of the course your own life takes, come to seem proleptic, to significant when other things don’t. (pp. 26–27)

Read a second time, this book functions very differently: it’s an account of the relationship of two people and a past that can’t be escaped. The festival’s production of Henry V, not the most obvious play, then makes sense, as does the follow-up of The Tempest. At the same time, there’s an aspect of the book – the anti-Stratfordian argument – which doesn’t quite fit with everything else. The narrator grows up to teach Elizabethan drama; he sidesteps the Shakespearean controversy, just as the academy does. Perhaps an answer can be found in the figure of Delia Bacon, whose quest to prove that Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare seems quixotic, if perhaps predicated on a life that didn’t work out as she would have liked. There is a romance to the anti-Stratfordians: their belief that the past contains a secret that could explain the present.

This is not, finally, a sentimental book: what seems to be pastoral is actually very carefully controlled by the narration. The title comes from an older book, by Mary Cowden Clark, seemingly an attempt to create backstories for Shakespeare’s heroines, perhaps that their behavior in the plays might be more comprehensible. One looks to the past for explanation.

The interior design of this book suffers a bit from the strange decision to use Zapf Chancery for the headers, with the resulting effect that it looks like it springs from the halcyon days when the Mac, Truetype fonts, and desktop publishing were brand new, a syndrome that might also be noticed in the lettering on Kate Bush’s The Hounds of Love, which had a somewhat more legitimate claim to the aesthetic, being released in 1985. What might possess a book designer to revisit that period twenty years later is beyond me, especially when the covers, done by another designer, are so lovely. It feels weirdly amateurish, the sort of thing you’d see in a church cookbook; and in its way it makes Crowley’s writing seem to be overly sentimental. It’s also strange that such attention would be paid to the covers while so little seems to be given to the interiors, though I guess that’s increasingly less surprising.