Detected little things: a peach-pit

basket watch-chain charm, an ivory

cross wound with ivory ivy, a natural

cross. The Tatoosh Mountains, opaque

crater lakes, a knickerbockered boy

who, drowned, smiles for a seeming ever

on ice skates on ice-skate-scratched

ice, an enlarged scratched snapshot.

Taken, taken. Mad charges corrupt to

madness their sane nurses. Virginia

creeper, Loose Tooth tanned black snake-

skins, shot crows for crow wings for

a black servant’s hat, lapped hot milk,

flung mud in a Bible reader’s crotch:

“You shouldn’t read the Bible nekkid!”

Family opals, selfishness changes hands.

Tatoosh Mountains, opaque crater lakes,

find me the fish skeleton enclosed in

a fish skeleton (fish ate fish) he had.

Author Archives: dbv

noted

- Matthew Herbert’s One Pig project.

- David George Pearson’s collection of Penguin book designs on Flickr.

- Stacy Szymaszek on PennSound.

- Malcolm Bradbury interviews William Gaddis (from 1986) at the British Library’s audio archive.

- Nic Rapold on adapting Coetzee’s Disgrace for the screen.

the printer’s error

Fellow compositors

and pressworkers!

I, Chief Printer

Frank Steinman,

having worked fifty-

seven years at my trade,

and served five years

as president

of the Holliston

Printer’s Council,

being of sound mind

though near death,

leave this testimonial

concerning the nature

of printers’ errors.

First: I hold that all books

and all printed

matter have

errors, obvious or no,

and that these are their

most significant moments,

not to be tampered with

by the vanity and folly

of ignorant, academic

textual editors.

Second: I hold that there are

three types of errors, in ascending

order of importance:

One: chance errors

of the printer’s trembling hand

not to be corrected incautiously

by foolish professors

and other such rabble

because trembling is part

of divine creation itself.

Two: silent, cool sabotage

by the printer,

the manual laborer

whose protests

have at times taken this

historical form,

covert interferences

not to be corrected

censoriously by the hand

of the second and far

more ignorant saboteur,

the textual editor.

Three: errors

from the touch of God,

divine and often

obscure corrections

of whole books by

nearly unnoticed changes

of single letters

sometimes meaningful but

about which the less said

by preemptive commentary

the better.

Third: I hold that all three

sorts of error,

errors by chance,

errors by workers’ protest,

and errors by

God’s touch,

are in practice the

same and indistinguishable.

Therefore I,

Frank Steinman,

typographer

for thirty-seven years,

and cooperative Master

of the Holliston Guild

eight years,

being of sound mind and body

though near death

urge the abolition

of all editorial work

whatsoever

and manumission

from all textual editing

to leave what was

as it was, and

as it became,

except insofar as editing

is itself an error, and

therefore also divine.

(Aaron Fogel. Via Tom Christensen’s rightreading.)

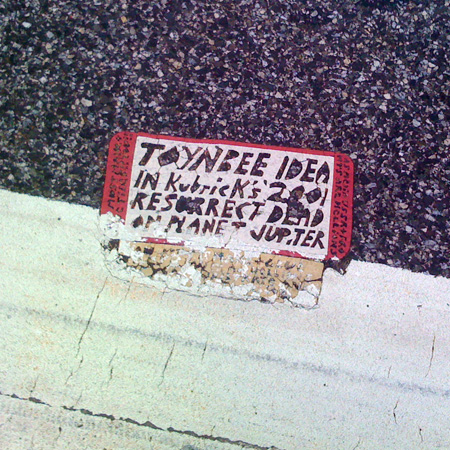

toynbee tile in philadelphia

august 26–august 31

Books

- Procopius, The Secret History, trans. G. A. Williamson

- Micheline Aharonian Marcom, The Mirror in the Well

- Georges Perec, Thoughts of Sorts, trans. David Bellos

- Donald Antrim, The Afterlife: a memoir

- Giorgio Manganelli, Centuria: 100 Ouroboric Novels, trans. Henry Martin

Films

- Baby Face, directed by Alfred E. Green

- Valerie a týden divů (Valerie and Her Week of Wonders), dir. Jaromil Jireš

Exhibits

- “Adventures in Modern Art: The Charles K. Williams II Collection,” Philadelphia Museum of Art

- “Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés,” Philadelphia Museum of Art

sixty-three

“An illustrious bell-caster, with a long beard and unconditionally an atheist, one day received a visit from two clients. They were dressed in black, and very serious, and showed a swelling on their shoulders, which made it cross the atheist’s mind that that was where their wings might be, as are said to be found on angels; but he paid this thought no attention, since it didn’t align with his convictions. The two gentlemen commissioned a bell of great dimensions – the master had never before made anything similar – and they wanted it cast in an alloy he had never before employed. They explained that the bell would emit a special sound, utterly different from the sound of any other bell. At the moment of departing, the two gentlemen explained, not without a trace of embarrassment, that the bell was to serve for Judgment Day, which by now was imminent. The master bell-maker laughed a friendly laugh, and said that there would never be a Judgment Day, but that all the same he would make the bell as indicated, and within the established time. The two gentlemen paid him a visit every two or three weeks to see how the work was proceeding. They were two gloomy gentlemen, and, despite their admiration for the master’s work, seemed secretly dissatisfied. Then, for a time, they didn’t return. Meanwhile, the master bell-caster had brought to completion the largest bell of his life, and recognized that he was proud of it; and in the secret place of his dreams he could see himself desire that so beautiful a bell, unique throughout the world, be used on the occasion of Judgment Day. When the bell had been finished, and mounted on a great wooden trestle, the two gentlemen reappeared; they looked upon the bell with admiration, and at the very same time with profound despondency. They sighed. Finally, the one who seemed more authoritative turned to the bell-caster and confessed in a low voice, ‘You were right, dear master; there will never be, neither now nor ever, any Judgment Day. There has been a terrible mistake.’ The master bell-maker regarded the two gentlemen, he too with a melancholy air, but his melancholy was happy and benevolent. ‘I’m afraid it’s too late, gentlemen,’ he said with a quiet, steady voice. He pulled the cord, and the great bell swung and sounded, loud and strong, and, as it had to be, the Heavens opened.”

(Giorgio Manganelli, from Centuria: 100 Ouroboric Novels, trans. Henry Martin, pp. 135–6.)

duchamp/roussel/kafka

“210 West 14th Street, New York City 6 Feb. 1950

My dear Carrouges,

Long after your letter I received the text, which I’ve read over several times.

It is true I am indebted to Raymond Roussel for having enabled me, from 1912 on, to think of something else instead of retinal painting (André Breton will enlighten you as to this term, because we have discussed it together), but I must declare that I have not read In the Penal Colony, and only read the Metamorphosis a number of years ago.

Just to let you know the circumstantial events which led me to the Mariée.

So I was astonished at the parallelism which you have so clearly established.

The conclusions you have come to in the sphere of ‘inner significance’ interest me deeply even though I do not subscribe to them (except as far as the glass is concerned).

My intentions as a painter, which have nothing to do with the deep result, of which I cannot be conscious, were aimed at the problems of ‘aesthetic validity’ obtained principally through the abandonment of visual phenomena, both from the retinal and the anecdotal point of view.

As for the rest, I can tell you that the introduction of a ground theme explaining or provoking certain ‘acts’ of the Mariée and the bachelors, never came into my mind – but it is likely that my ancestors made me ‘speak’, like them, of what my grandchildren will also say.

Celibately yours, Marcel Duchamp”

(Quoted on p. 49 of Le macchine celibi/The Bachelor Machines, ed. Jean Clair & Harald Szeemann, following the contribution by Michel Carrouges. This letter appears to have been translated from French to Italian before being put into English.)

august 20–august 25

Books

- Sarah Manguso, The Two Kinds of Decay

- Ronald Firbank, The New Rythum and Other Pieces

- Edmund White, Fanny: A Fiction

Films

- Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, directed by Mike Nichols

- Where the Boys Are, dir. Henry Levin

- The Bad Seed, dir. Mervyn LeRoy

Exhibits

- “Dormitorium: An Exhibition of Film Decors by the Quay Brothers,” The Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, Parsons

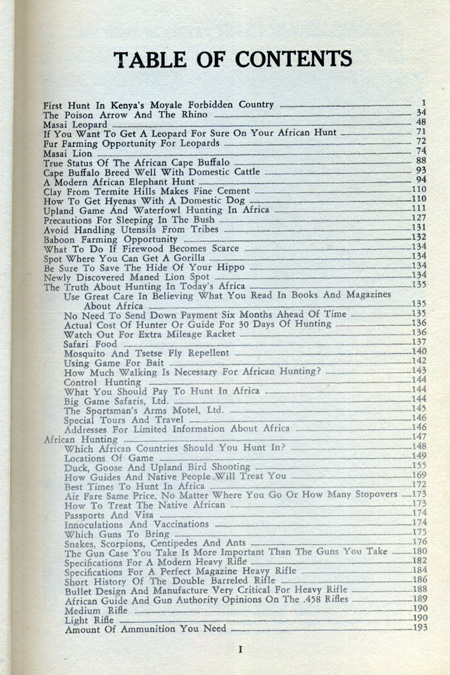

the truth about hunting in today’s africa

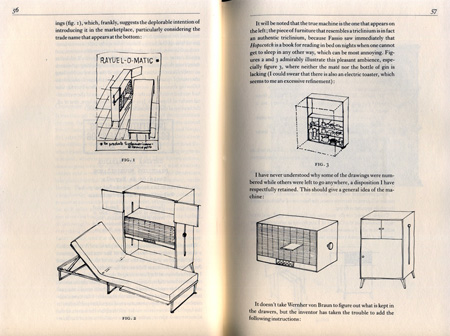

a machine for reading hopscotch

(Juan Esteban Fassio’s “Hopscotch-o-matic,” illustrated on pp. 56–7 in Julio Cortázar’s Around the Day in 80 Worlds, trans. Thomas Christensen.)