Louis Lüthi

Louis Lüthi

On the Self-Reflexive Page

(Roma Publications, 2010)

Louis Lüthi sent me a copy of his book: it’s always a pleasant surprise to find a package in the mailbox from Amsterdam. Opening it, I immediately felt guilty for the pile of unread copies of Dot Dot Dot sitting on my to-be-read pile: I’m not sure why – and I should interrogate myself about this – but after a certain point, I stopped reading issues of that magazine, one of the last magazines that felt absolutely necessary to me, as soon as they arrived. And so I missed the original publication of Louis Lüthi’s essays on books that use the page in non-traditional ways, which is a shame. Or maybe not: when this would have come out, I was feeling burnt out when it came to thinking about the form of the book; now there’s more space, and I can give this the thought it deserves.

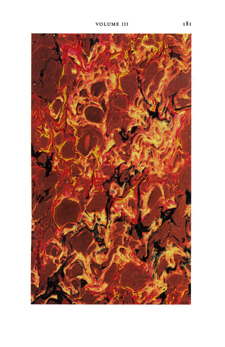

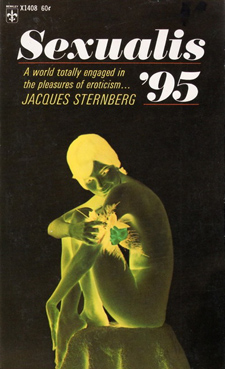

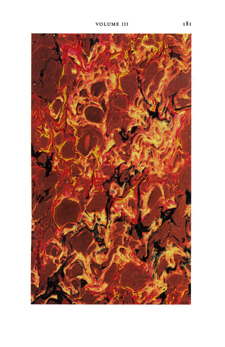

The cover (and back cover) should be immediately recognizable: the marbled pages from Tristram Shandy, which I suddenly realized I’d never seen in color, only grayscale reproductions; one forgets, as well, that the marbled page is actually two marbled pages, a marbled leaf. (With more money & space than I have, a complete collection of editions of that book would be a fine thing to assemble and exhibit: some aspiring Alÿs should get on that project.) The interior of Lüthi’s book consists of first 118 full-page reproductions of other book pages, then an extended essay about what those pages signify, followed by notes and a bibliography. The reproductions of pages have been divided into Black Pages, Blank Pages, Drawing Pages, Photography Pages, Text Pages, Number Pages, and Punctuation Pages. Lüthi’s book is an attempt to create a taxonomy for how non-textual pages function in fiction; his sections on Black Pages, Blank Pages, and Drawing Pages naturally start with the black pages, blank pages, and marbled pages that Sterne uses.

Flipping through the illustrations, one recognizes old friends: Gass is here, as is Perec, Zo’s illustrations to Roussel, Alasdair Gray, B. S. Johnson, Sebald, John Barth. Broodthaers’s crossed-out Mallarmé is here, though it stands out a bit: most of Lüthi’s other examples are more clearly pages of fiction. Rousse is another outlier (as he always is), as are Dieter Roth (here telling stories), two of Aram Saroyan’s visible poems, and the map of the ocean from The Hunting of the Snark, also included in Perec’s stripped-down reproduction (from, it should be noted, one of his non-fiction excursions). There are also pages from more recent writers: Douglas Coupland, Dave Eggers, Jonathan Safran Foer, Salvador Plascencia, Lorrie Moore, Steven Hall. It’s a useful anthology: while a number of histories of visual poetry or text-based visual art are available, it’s harder for me to think of a compilation of fiction that uses visual devices.

Lüthi’s essay considers how these pages are used in the text. Here, his consideration starts with Nabokov and Cortázar: this is a sensible move. Both of these writers might be seen as being in this tradition, but not completely of it; both have characters who suggest a textual device rather than directly presenting it to the reader. Humbert Humbert instructs his printer to fill the page with Lolita’s name; a page of Morelli’s work filled with a single sentence is described in Hopscotch. (Cortázar’s strategies might not be as non-textual as Lüthi suggests: the chapter in Hopscotch where lines are interleaved is not included here, nor is the use of illustration in his non-fiction considered.) There’s a remove from the strategy that Sterne followed here, of course: but conversely, the work of Nabokov and Cortézar can be seen as completely fictional, not breaking into the visual.

There’s a peril that comes with showing and not telling which feels familiar to me: the young expositors of playing-with-the-page (Jonathan Safran Foer, Reif Larsen, Dave Eggers, etc.) are not, for the most part, creating books that felt the need to engage with in any substantive way. I do periodically go to the bookstore, pick up these books which I know I should be interested in – they’re quite visibly coming from a heritage I’m interested in – and put them down, not quite seeing what’s interesting in them. (This isn’t simply a problem with younger writers: I have the same problem with Danielewski and much of B. S. Johnson’s page-based experimentations, though I’ll give House Mother Normal and The Unfortunates – neither mentioned here – a pass.) Why do I react positively to (generally older) visual poetry, or to Alasdair Gray or William Gass, but not to something like Foer’s Humumented edition of Bruno Schulz? Fear of gimmickry? Perhaps its the sense that the visual is there something that’s simply been roped into the service of fiction, rather than something that’s interested in exploring the space between forms. Or maybe it’s a problem with seeming played-out, not experimental enough. There’s a useful passage in “Blank Pages” (the essay portion of this book is not paginated):

But a blank page in 21st-century literature cannot be the same thing as a blank page in the 20th century, much less one in the 18th; time erodes originality and alters meaning, and what was considered a tabula rasa a century ago could not be regarded as facile legerdemain.

This is a position akin to that taken in a passage in Umberto Eco’s The Open Work where Eco discusses Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1, a book-in-a-box where every page gets its own leaf, astonishingly translated into English and published in the late 1960s:

I recently came across Composition No. 1, by Max [sic] Saporta. A brief look at the book was enough to tell me what its mechanism was, and what vision of life (and obviously, what vision of literature) it proposed, after which I did not feel the slightest desire to read even one of its loose pages, despite its promise to yield a different story every time it was shuffled. To me, the book had exhausted all its possible reading in the very enunciation of its constructive idea. Some of its pages might have been intensely “beautiful,” but, given the purpose of the book, that would have been a mere accident. Its only validity as an artistic event lay in its construction, its conception as a book that would tell not one but all the stories that could be told, albeit according to the directions (admittedly few) of an author.

What the stories could tell was secondary and no longer interesting. Unfortunately, the constructive idea was hardly more intriguing, since it was merely a far-fetched variation on an exploit that had already been realized, and with much more vigor, by contemporary narrative. As a result, Saporta’s was only an extreme case, and remarkable only for that reason. (trans. Anna Cancogni, p. 170)

Eco’s right here, I think; but it shouldn’t come as a surprise that he turns up in Lüthi’s book with a page from Foucault’s Pendulum, ostensibly a record of a computer printout of the 720 possible names of God.

Reading this book, I found my thoughts returning to Susan Howe’s poetry: That This, which I should still write about, and The Midnight, her volume which considers the interleaf. Howe’s work is intensely visual: but it also springs from the history of the visual, the history of American letters and the documents that compose it being one of her primary concerns. Howe’s work feels astonishingly powerful to me, as vibrant of that of anyone working today. Here’s text from the beginning of The Midnight from the space where an epigraph would go: it faces a mirrored facsimile of the interleaf covering the title page of The Master of Ballantrae, a subject of that book:

There was a time when bookbinders placed a tissue interleaf between frontispiece and title page in order to prevent illustration and text from rubbing together. Although a sign is understood to be consubstantial with the thing or being it represents, word and picture are essentially rivals. The transitional space between image and scripture is often a zone of contention. Here we must separate. Even printers and binders drift apart.. Tissue paper for wrapping or folding can also be used for tracing. Mist-like transience. Listen, quick rustling. If a piece of sentence left unfinished can act as witness to a question proposed by a suspected ending, the other side is what will happen. Stage snow. Pantomime.

“Give me a sheet.

Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro