- Susan Howe & David Grubbs’s Thiefth is online at PennSound.

- Audio recordings from former slaves at the Library of Congress

- The Brooklyn Rail is having a reading in honor of Gilbert Sorrentino on Saturday, February the 20th with Walter Abish & David Markson, among others.

- Also at the Brooklyn Rail: John Yau’s “The Difference between Jerry Saltz’s America and Mine”, a good examination of arts in New York in the past decade.

at the met

(Couple with Anthropomorphic Deity; Mexico; Maya; 7th–9th century; ceramic. Lent by a private collection, 2008. L.2008.41.8)

february 1–february 5

Books

- Éric Rohmer, Six Moral Tales, trans. Sabine d’Estrée

Films

- My Man Godfrey, directed by Gregory La Cava

- Laberinto de pasiones, dir. Pedro Almodóvar

- Le genou de Claire (Claire’s Knee), dir. Éric Rohmer

- La cambrure, dir. Edwige Shaki

- L’amour l’après-midi (Love in the Afternoon), dir. Éric Rohmer

- Véronique et son cancre, dir. Éric Rohmer

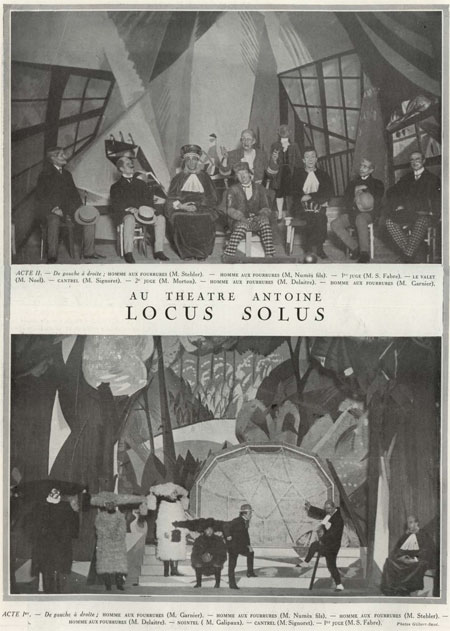

locus solus at the theatre antoine

(Illustration from Le Théâtre et Comoedia illustrée of the original theatrical production of Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus in 1923, from Livrenblog by way of A Journey Round My Skull.)

learn to snap

“But this knowledge of history did not deflect my sadness. She saw my whole despair and, one afternoon as I returned home from the club, she said: “Perhaps even now it is not too late. Change style. Learn to snap. Leave government service, plunge into jungles of commerce.”

(Donald Barthelme, “Snap Snap,” Guilty Pleasures, p. 33.)

éric rohmer, “six moral tales”

Éric Rohmer

Éric Rohmer

Six Moral Tales

(trans. Sabine d’Estrée)

(Viking Press, 2009)

Amazon had the Criterion Six Moral Tales box set for cheap after Éric Rohmer died; I took them up on it, and I’ve been working my way through them. The box set includes six DVDs; in addition to a booklet of critical essays, Rohmer’s book of short stories made from the films is also included. It’s a substantial book (262 pages); off the top of my head, I can’t think of other editions of films that have privileged a text counterpart so much. Criterion’s edition of Last Year at Marienbad, for example, doesn’t include the out-of-print Grove edition of the book, illustrated with the film stills. Nor are there that many films that are so directly connected to literary fiction authored by the director: Antonioni’s That Bowling Alley on the Tiber comes to mind, but there’s a difference between the short stories in that and the films. There’s Marguerite Duras, of course, and Georges Perec, but the films they directed aren’t especially well-known; the exception might be Duras’s India Song.

I’ve been reading the stories after watching all the films, so it’s taken me a while to make my way through this. Reviews of the Six Moral Tales often say that they’re based on a novel; the back cover of this edition says that “years before Eric Rohmer turned to filmmaking, he wrote his famed Six Moral Tales in book form,” which echoes Rohmer’s statement in his preface that the stories “are not adapted from my films.” These assertions are misleading; Rohmer’s is disingenuous. This isn’t a novel; rather, it’s six short stories where the same basic plot (boy has girl; boy meets other girl; boy considers straying) is reenacted, almost in the manner of Queneau’s Exercises in Style. The French copyright date on this is 1974, two years after the last of the films; in addition, it seems clear that these stories were (at the very least) reworked after the making of the films, something more noticeable because the stories and the films are extremely similar.

At the start of the film of La Collectionneause, for example, is a scene where a painter, played by Daniel Pommereulle, talks to an art critic, played by Alain Jouffroy. Jouffroy disappears from the film after this scene; the painter, who is the third-most important character in the film, is identified by others as “Daniel”. The viewer may not know that Jouffroy is best known as an art critic, and that Pommereulle is generally known as an artist. This situation is further confused by the same scene’s treatment in the text:

Daniel – Daniel Pommereulle, to give his full name – is one of those contemporary painters who durin the sixties tossed their paintbrushes into the garbage and turned their creative energies to the manufacture of “objects.” The art critic Alain Jouffroy called them “Objectors,” and in the art magazine Quadrum published an article under this title devoted to their work. The year is 1966, and Jouffroy is paying a visit to Daniel’s studio. (p. 129.)

The article mentioned actually exists – “Les Objecteurs: La ‘Distance infinie’ de Duchamp,” Quadrum, no. 19, 1965, pp. 6–9. La Collectionneuse was released in 1967; possibly the scene was shot in 1966. One wonders, however, whether the conversation between Jouffroy and Pommereulle that follows is theirs or Rohmer’s. The acting credits in the film begin “avec la collaboration pour l’interprétation et les dialogues de”; what’s said in the film is very close to the text, but inexact. Although it’s isolated, almost certainly their scene in the film isn’t documentary: there’s too much relevance to what happens later. The first paragraph of the story, titled “Haydee,” physically describes the main character of the story; the name of this character, the “collectionneuse” of the title, is that of the actress Haydee Politoff, and the description physically matches the actress.

Or again: in “Claire’s Knee,” Jerome explains to Madame W. and Laura that “he and Aurora first met, six years before, when he was the cultural attaché in Bucharest” (p. 173). Why Bucharest? Presumably because Aurora Cornu, who plays a writer in the film, is a Romanian writer. There’s a further overlay here: Aurora (the character) is a writer and claims that she wants to write use Jerome as a character in her book. It’s not by chance that Aurora and Jerome look at a painting of Don Quixote: as Vargas Llosa noted, in the first book, Quixote makes the mistake of trying to read the world through the lens of a book, while in the second, the world, having read the book about Quixote, keeps expecting him to act like a character in it. Rohmer’s introduction again: “My heroes, somewhat like Don Quixote, think of themselves as characters in a novel, but perhaps there isn’t any novel.”

All of these stories tell the story of a male lead who passes through a point of crisis; all of the narrators attempt to justify their generally reprehensible behavior to themselves with flimsy reasoning, the morality of which is belied by the damage they end up doing to others. The most interesting use of this is in the fifth story, “Claire’s Knee,” where Jerome justifies his desire to be unfaithful by explaining to his novelist friend Aurora (who may be a past lover) that he’s acting in the interest of providing her with a story. There’s a distinct echo here of Choderlos de Laclos: and while Aurora, who is at least partially a stand-in for the director, finds his storytelling useful, she’s aware that his stated reasons aren’t his real ones. As in Les Liaisons dangereuses, the relationship between these two characters is more interesting than what they’re plotting; Jerome, however, isn’t aware enough to notice Aurora’s interest in him, or to notice that she, who he has taken as single, has her own distant fiance. The libertine echoes return in “Love in the Afternoon”: early on, the narrator describes his escape by reading in the subway:

On the train, I much prefer reading books to newspapers, not only because newspapers are cumbersome but also because I can’t immerse myself in the papers. Books lead me further afield, and at present I’m very much taken with books on exploration. Today’s book is entitled Voyage autour du Monde by Bougainville. (pp. 217–8.)

Bougainville’s description of Tahiti as paradise, source of the idea of the “noble savage” almost certainly isn’t what the narrator is reading: more likely he’s reading Diderot’s response, Supplément au voyage de Bougainville which sees in the sexual freedom of the Tahitians a model for the libertine reinvention of Western society. (In the film, it’s clear that the narrator’s edition includes Diderot’s supplement.) This also presages Chloe’s later argument against marriage, which the narrator finds tempting, but rejects, that polygamy isn’t degrading to women if women also practice it. For the narrator, it’s an escape from his present bourgeois reality; but it’s not one that he will follow up on.

These stories can’t be separated from the films, and were presumably meant to be read in conjunction with them, although this would have been very difficult for most readers in the 1970s when the films wouldn’t have been immediately accessible as they are now. The films were made from 1962 to 1972; they blossom from black and white shorts about students to full-color feature films about first affianced and finally married couples. While the characters don’t recur – save for a dream sequence in Love in the Afternoon, not reflected in the story – there’s an implicit story of growth, of a director growing more confident with himself. This growing maturity isn’t reflected as much in the stories: while the stories are more complex, Rohmer isn’t interested as much in the different ways that narrative voice can function in fiction. Most of these stories are told in the first person, echoed strongly by the voiceovers of the first films. “La Collectionneuse” starts in the third person from several perspectives (the film’s “prologues”) before it switches to the first. Only “Claire’s Knee” differs, being told in a the third person; this is generally from the perspective of Jerome, but at the end it suddenly switches over to Aurora with a scene that could only be seen by her: “The boy’s left arm is around Claire’s shoulder, and his right hand is caressing her knee.” (p. 213) This isn’t quite reflected in the film: there, the actors sit on a bench with their backs to the camera. The boy may be caressing her knee with his left hand (which would have mattered more to Jerome than to Aurora), but the viewer can’t see this; had the viewer not read the text, they almost certainly would not have presumed this. These are stories that are better told as films, where the camera’s perspective can be unhinged from the task of straightforward narration.

noted

- Audio of Weldon Kees, recorded in Berkeley in 1952, is available at the Poetry Foundation.

- An excerpt from the new Gilbert Sorrentino novel is up at the Brooklyn Rail.

- Douglas Messerli of Sun & Moon/Green Integer has a new blog, American Cultural Treasures.

- A short piece on Victorian collage that I wrote at Hotel St. George.

january 26–january 31

Books

- Tom Frank, ed., The Baffler #7: The City in the Age of Information

- Nick Smith, aka “ulillillia,” The Legend of the 10 Elemental Masters

Films

- Primate, directed by Frederick Wiseman

- Titicut Follies, dir. Frederick Wiseman

- Drei Wege zum See (Three Paths to the Lake), dir. Michael Haneke

- A History of Violence, dir. David Cronenberg

- Entre tinieblas (Dark Habits), dir. Pedro Almodóvar

- Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón, dir. Pedro Almodóvar

the baffler #7: the city in the age of information

The Baffler #7: The City in the Age of Information

The Baffler #7: The City in the Age of Information

ed. Thomas Frank

I’m still working my way through back issues of the Baffler. This one was laid out in June 1995; after quotations from Randolph Bourne and Edmund Wilson, the copyright page proudly announces that they don’t have an email address (or telephone). Tom Frank’s “Twentieth Century Lite” lays out the theme for the issue: the rhetoric of the right, led by Newt Gingrich, had it that the rise of the information age obviated the need for cities. Everything was about to change. Some things haven’t changed: David Brooks was spouting idiocies back then as well, but for the City Journal rather than the New York Times. A George Gilder quote stands out: “The telecosm can destroy cities because then you can get all the diversity, all the serendipity, all the exuberant variety that you can find in a city in your own living room.” I don’t think that anyone’s still trotting out this idea in a positive sense, at least not publicly, but it’s hard to ignore the effects of the internet, often adverse on the city: there’s no reason for neighborhood book stores if you can get anything cheaper through Amazon.

It’s hard to tell what the idea was with fiction; no fiction editor is listed, although there are poetry and art editors. Short pieces by Janice Eidus and David Berman seem consistent with Baffler style, even if neither is particularly noteworthy; the Berman would work better if it had been declared prose poetry. A brief piece by Irvine Welsh – an excerpt from The Acid House about a trip to Disneyland – feels out of place: reading Scots dialect in this context, one can’t help but think of James Whitcomb Riley. One forgets, though, how much Welsh’s literary reputation declined in this country. Another piece, by Tibor Fischer, doesn’t do much for me; taken together, the two suggest an interest in British models for describing society in fiction, but that isn’t quite matched by the quality of the prose. The poetry – edited by Damon Krukowski – is noticeably better.

Naomi Klein, pre-No Logo:

But what does it mean when the still existing malt shop (or cafe or pub or laundro-mat) becomes cyberspace? What does it mean when you leave your house, go to public, urban spaces and spend the entire time ignoring the people around you in favor of finding out more about some angster in Texas named Bryon who has posted his entire diary on the internet in all of its excruciating detail, including a picture of his ex-girl friend Sandi’s cat and the heartwarming description of his relationship with his best friend Kriss: “We do a lot of things together, usually related to computer hardware (buying, selling, fixing).”

This isn’t a particularly good piece – bemoaning the wave of hype that then surrounded cybercafes – but here she gets to something useful, anticipating most of the next decade.

The bulk of the issue is spent examining the current state of the city. The last piece in the book, “A Machine for Forgetting” sees Tom Frank examining Kansas City, getting started on the job of figuring out what the matter with Kansas was. Kim Phillips takes on Chicago, briefly; Robert Fiore looks at Los Angeles selling off its infrastructure. Steve Healy and Dan Bischoff cover Athens and Atlanta, respectively, and a Maura Mahoney review Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil accuses John Berendt of cultural tourism in Savannah. Paul Lukas’s “Forty-Two Pickup” surveys Times Square while Disneyfication was underway but not yet assured of success: it’s a familiar story by now, but the portrait of a New York that still seemed to be wavering between identities. It can be hard to remember now how much the middle of the country’s perception of New York has changed. Lukas’s predictions of the future, like most predictions of the future, are entirely wrong, but it’s good to be reminded that there was a point when an alternative could be imagined.

Most interesting to me was Diamonds Mulcahey’s “Screw Capital of the World,” a survey of the history of Rockford, Illinois, the crumbling city where I was born. There was not a great emphasis on the history of Rockford when I grew up; common consensus was that it was too boring to have a history. The opening of a piece by Calvin Trillin in the New Yorker from 1976 which Mulcahey points out gives a good idea of the civic tenor:

In Rockford, there is always a lot of talk about negativism. Rockford people discuss negativism the way college students in the fifties discuss apathy – as an endemic, mildly regrettable, permanent condition. Apathy is also discussed in Rockford, usually in conversations about negativism.

Trillin’s article covers Rockford at a moment when extracurriculars had been dropped in the public schools because the voting public wouldn’t vote for increased property taxes; my high school was similarly threatened just before I arrived there, but sports were deemed too important. Trillin also points out that forced busing in the schools was an enormous issue even then; this was still dragging through the courts long after I’d left and Mulcahey’s article was written.

Mulcahey’s piece starts with a history of the Palmer raids of 1920, when 180 suspected Communists working in the tool-making and furniture factories were arrested. I’d never heard of this; Wikipedia, which manages to covers Cheap Trick repeatedly, also seems to have missed how the Rockford Daily Republic had declared Rockford to be “a veritable breeding palace for those who plot the overthrow of the United States by force.” Clarence Darrow successfully defended a Swede against charges of sedition. It’s not surprising that this would have fallen out of the historical narrative, but it does help explain how Rockford fell apart as a city. In 1945, Rockford was the “Screw Capital of the World”; but by the time I was growing up, that nickname had been forgotten, and we learned that it was the “Forest City,” on account of the elm trees that lined the streets before Dutch elm disease. (The visitor’s bureau seems unhappy about “Screw Capital of the World”.) In 1945, Life portrayed Rockford as an illustration of “the phenomenon of social mobility.” But Rockford was anomalous early on for being a right-leaning blue-collar city, which comes across strongly in the Trillin piece from 1976, when he finds that everyone is unwilling to pay for education. Industry left; by 1993, Money magazine rated Rockford the worst place to live of the 300 largest American cities.

This is a fantastic piece, anticipating a great deal that’s happened in the politics of the middle of the country since; it’s unfortunate that this piece seems to have no representation at all online. I suspect this wasn’t collected because of the similarity with Frank’s Kansas City. Fitting, really, for a second city to a second city.

noted

- LACMA has been digitizing old catalogues, which are now online using the Internet Archive’s book presentation software.

- Warren Motte in conversation with Martin Riker at Words Without Borders.

- Michael Haneke’s Three Paths to the Lake, his 1976 film adaptation of an Ingeborg Bachmann short story, is showing tomorrow at 7:30 at Anthology Film Archives, part of a series of adaptations of Austrian writers put on by the Austrian Cultural Forum.