- Joanna Scott on David Markson’s late books at The Nation.

- An attempt to point out who owns who in the American publishing landscape.

- A fine post by Waggish on difficulty in reading and music, with some reference to Steven Moore but mostly to Milton Babbitt.

- A useful breakdown of the works of John Cowper Powys; and John Yau on Christopher Middleton.

- There’s probably something to be said for this Chris Fujiwara essay on cinema and the problem of the contemporary; this seems like an argument that could be expanded beyond that medium.

- And Triple Canopy is putting on Forms of Crisis with Joseph McElroy and Harry Mathews on Thursday October 21; unfortunately, I’ll be in L.A.

Yearly Archives: 2010

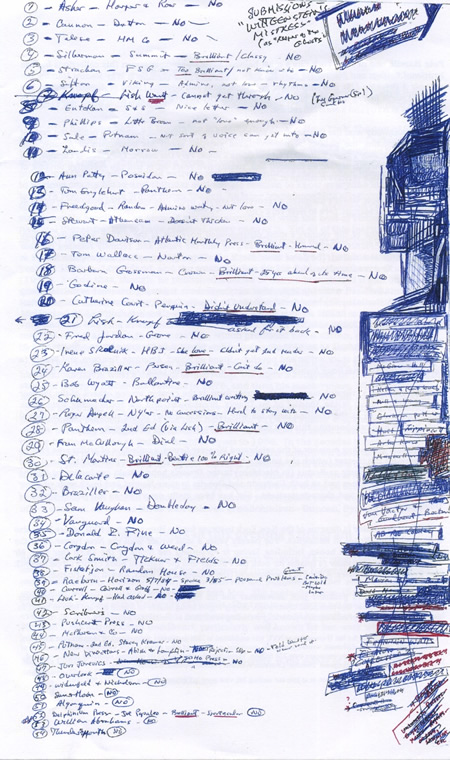

jorge luis borges, “doctor brodie’s report”

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges

Doctor Brodie’s Report

(trans. Norman Thomas di Giovanni & Jorge Luis Borges)

(Bantam Books, 1973)

Continuing my re-reading of Borges: this is the original translation of his penultimate volume of short stories, here published as a lurid paperback while he could still be referred to on the cover as “one of the world’s great living writers.” It’s odd, somehow, to think of reading Borges while he was still alive, especially when he could have been read in paperback; it seems like Borges has always been dead, his corpus of works petrified and preserved, a feeling encouraged by generally seeing him now in the context of his complete fiction, which one tends to assume is a consistent whole. Borges in paperback seems like something different: this collection of short stories can be judged as a book. It’s strange to realize that, chronologically, the religious fantasia of “The Gospel According to Saint Mark” is might be seen as reminiscent of Gaddis’s The Recognitions rather than the other way round. It’s also odd to realize that at the point in time when this was published Cortázar was publishing better collections of Borges-influenced short stories.

The two stories that I remember from this are the title story and “The Gospel According to Saint Mark,” which I think I re-read a couple years ago for reasons I do not remember. Those two, as it turns out, are the standouts of this volume; as with The Book of Sand, this is decidedly minor Borges. The majority of the stories here do not come off as especially Borgesian, something those in The Book of Sand would actively attempt: here, there’s little preoccupation with paradox, and most of these are almost straightforwardly realistic, albeit depicting an imagined Argentina (and Uruguay – there’s a lot of Uruguay in this book) that may or may not have existed. There’s a great deal of knife-fighting, and if you’re not interested in knife-fighting much of this book may be lost on you. In his introduction, Borges notes that he was attempting to mimic the late short stories of Kipling, which I haven’t read; maybe some brave soul out there is making the case for Kipling today, but this seems like a strategy not likely to win many admirers. These stories of Kipling, he declares in his preface, “doubtless surpass” those of Henry James and Kafka; they are “laconic masterpieces” conceived when young but written when old. Henry James, meanwhile, is explicitly pastiched in “The Duel”; but the characters in the story, ostensibly about two female painters in Argentina of the 1960s, seems ludicrously unbelievable, as might perhaps be expected to be the case for a blind man writing about contemporary art. This might not be so bothersome if the story weren’t so mundane and the characters didn’t seem like they could have been borrowed, without changes, directly from James: perhaps Borges is trying to claim that Buenos Aires in the 1960s was the same as Boston or London in the 1880s, which seems bizarre to the point where this reader, at least, lost faith in the writer.

What might be most interesting about this particular book is the translation: this is the original translation of this book, which is out of print. Penguin evidently brought out a version of this; they’ve replaced it with the Andrew Hurley version from the Collected Fiction. This is something of an odd choice, given that this particular edition was translated with the collaboration of Borges: it includes a forward cosigned by Borges and di Giovanni, as well as an afterword by Borges that don’t appear in the Collected Fiction; I assume they don’t appear in the new Penguin Brodie’s Report. The foreword explains how this volume came to be:

One difference between this volume and the last lies in the fact that the writing and the translation were, except in one case, more or less simultaneous. In this way our work was easier for us, since, as we were always under the spell of the originals, we stood in no need of trying to recapture past moods. This seems to us to be the best possible condition under which to practice the craft of translation. (p. viii)

It’s odd that this translation should appear to be deprecated; as a translation, I think it’s substantively better than the Hurley version. (As I don’t have a Spanish edition, I can’t make any arguments about which is more correct; but given Borges’s seemingly direct involvement in this one, it seems like it would be difficult to argue that the earlier translation swerved from Borges’ intention.) Compare the final paragraph of “The Gospel According to Mark,” first in the Hurley translation:

The three of them had followed him. Kneeling on the floor, they asked his blessing. Then they cursed him, spat on him, and drove him to the back of the house. The girl was weeping. Espinosa realized what awaited him on the other side of the door. When they opened it, he saw the sky. A bird screamed; it’s a goldfinch, Espinosa thought. There was no roof on the shed; they had torn down the roof beams to build the Cross. (p. 400 in Collected Fictions.)

Here’s di Giovanni:

The three had been following him. Bowing their knees to the stone pavement, they asked his blessing. Then they mocked at him, spat on him, and shoved him toward the back part of the house. The girl wept. Espinosa understood what awaited him on the other side of the door. When they opened it, he saw a patch of sky. A bird sang out. A goldfinch, he thought. The shed was without a room; they had pulled down the beams to make the cross. (p. 13)

Neither of these is without its infelicities: I don’t entirely understand why di Giovanni would use “mocked at him” rather than “mocked him”; “Bowing their knees” is a little strange; and “the back of the house” is better than “the back part of the house.” But on the whole, the di Giovanni seems much better to me: the “of them” in the first sentence seems extraneous; “stone pavement” is better than “floor”; “mocked” is better than “cursed”; “shoved” better than “drove”. “The girl wept” seems better than “The girl was weeping” as it brings to mind “Jesus wept.” The italics for Espinosa’s thought is unnecessarily distracting, and di Giovanni’s handling of these two phrases works better. Goldfinches don’t “scream,” they “sing.” And the capitalization of “Cross” makes it seems like a machine to be “built” rather than something made by human hands.

There are numerous differences between these two editions, some seemingly more serious than others. In the Preface, for example, “The Gospel According to Mark” is attributed to “a dream of Hugo Rodríguez Moroni” in the di Giovanni but “Hugo Ramírez Moroni” in the Hurley; a Google search reveals Spanish hits for both, and a note in Hurley suggests that he hasn’t found an antecedent for this Moroni; in the next paragraph “Paul Groussac” in the di Giovanni” turns into “Paul Grossac” in the Hurley, which makes one wonder. David Brodie, protagonist of the title story, loses the “D.D.” that he’s given in the di Giovanni translation; perhaps Hurley decided that he wasn’t a real doctor. In the same story, a book is cited in di Giovanni as “one of the volumes of Lane’s Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (London, 1839)”; in Hurley this becomes “the first volume of Lane’s translation of the Thousand and One Nights (An Arabian Night’s Entertainment, London, 1840). A few sentences later in the story suggests the difference in tone – first the Hurley:

Their food is fruits, tubers, and reptiles; they drink cat’s and bat’s milk and they fish with their hands. They hide themselves when they eat, or they close their eyes; all else, they do in plain sight of all, like the Cynic school of philosophers. (p. 403)

Di Giovanni’s version of the same:

They take their nourishment from fruits, root-stalks, and the smaller reptiles; they imbibe the milk of cats and of chiropterans; and they fish with their hands. While eating, they normally conceal themselves or else close their eyes. All other physical habits they perform in open view, much the same as the Cynics of old. . . . (p. 135)

I like di Giovanni’s version much better, not least because he uses “chiropterans” rather than “bats”; but his version feels more like the ersatz nineteenth-century document that this story purports to be. Perhaps it’s less accurate; but it reads much better than the current translation. I don’t think this is an essential volume of Borges, but if it is to be read it deserves to be read in the original translation.

october 1–october 10

Books

- Gabriel Josipovici, Writing and the Body

- Alice B. Toklas, What Is Remembered

- Ted Nelson, Possiplex: Movies, Intellect, Creative Control, My Computer Life and the Fight for Civilization

Films

- Boxing Gym, directed by Frederick Wiseman

- Le nain, dir. Louis Feuillade

- La nativité, dir. Louis Feuillade

- The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, dir. John Badham

- North Dallas Forty, dir. Ted Kotcheff

- Mistérios de Lisboa (Mysteries of Lisbon), dir. Raúl Ruiz

ted nelson’s student movie

(From Ted Nelson‘s The Epiphany of Slocum Furlow, shot in 1959 according to his autobiography.)

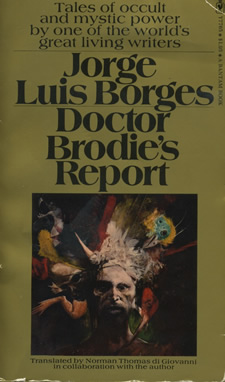

gabriel josipovici, “writing and the body”

Gabriel Josipovici

Gabriel Josipovici

Writing and the Body

(Princeton University Press, 1982)

I stumbled across this in the stacks of Schoen Books last week, where I was also assured by its previous owner that it was fantastic. I don’t know if I’ve ever actually seen a copy of this book before (as far as I can tell, this hardcover edition is the only release this book had, though I certainly could be wrong); but his books are interesting enough that I buy them when I find them. This is a small book: it’s composed of four lectures, given at the University of London in 1981, which don’t seem to have been reworked for publication. Each lecture is around 32 pages, or a long essay; as they were originally given over four weeks, each builds on the previous. There’s the feeling of a work in progress: these lectures feel more like attempts at understanding a problem, rather than clearly defined arguments; this was, Josipovici writes in his brief introduction, his intent. It’s an interesting project, almost thinking aloud; it won’t appeal to everyone, but I like it.

The problem that Josipovici is considering here stems from his own career as a novelist: that to write the writer must remove him or herself from the world; writing thus might be seen to be in opposition to living. Here’s how he puts it in his preface:

While one is at work on an extended piece of fiction (and I imagine it is the same with painting and music) one has no desire to see anyone or to read anything. Everything seems to be an intrusion. It is not so much that one is afraid the book might be damaged by such contact – though that comes into it – as that nothing interests one except what one is working on. This total absorption is a blessing. But it is also a tyranny. As one nears the end of such work one longs for other voices, for the company of one’s friends, of books. One feels one has been away from the world too long and one want to integrate oneself with it, to ‘live’ again. But this is very curious. One leaves the world because one feels the need to write in order to come fully alive, and then one is glad writing is coming to an end because in the later stages it was starting to feel more like death than life. Does the act of making on which the artist is engaged bring him more fully in touch with his real self and with the world, or does it take him further away from both? (p. xiv)

This subject expands or shifts slightly to encompass the relating of writing to the body, and then to the problem of how the maker understands what’s being made while it’s being made. The first essay makes its way through Tristram Shandy, an obvious place to start thinking about the subject, but always a rewarding text to return to: here we find the beginning of the problem taken up more recently by Harry Mathews in The Journalist or Tom McCarthy in Remainder, the problem of reproducing something (a life, a memory) while still living. Sterne doesn’t get very far in relating Tristram Shandy’s life as a biography; but, Josipovici points out, he inscribes his life in the text, using similar strategies:

And just as Tristram’s nose is put together by Dr Slop with ‘a piece of cotton and a thin piece of whalebone out of Susannah’s stays’, so the book is contrived out of an old sermon of Sterne’s, the name of a character who is already only a skull in Shakespeare, some typographical tricks, and bits and pieces out of a variety of sixteenth and seventeenth century authors. (p. 7)

Tristram Shandy is a narrative of failure; but the book, Josipovici argues, does not fail itself because a novel can take failure as a subject. An interesting bit of Lévi-Strauss is pulled in:

[T]he horse does effectively give birth to the horse, and . . . through a sufficient number of generations, Equus caballus is the true descendent of Hipparion. The historical validity of the reconstruction of the naturalist is guaranteed, in the last analysis, by the biological link of reproduction. On the other hand, an axe never engenders another axe; between two identical tools which are different but as near neighbours in form as one would wish, there will always be a radical discontinuity, which comes from the fact that the one has not issued from the other, but both from a system of representations. (p. 10)

The book, Josipovici points out, is like the horse in that it does issue from biological life: it includes, especially if it is a book like Tristram Shandy, a record of its own making. But it’s also like the axe, a cultural product. Writing a book takes time; reading a book takes time:

The writer who senses the possibilities of his craft is in control of the reader of his book; he can play with time in it, stop, move off in a different direction, turn round suddenly and pounce on the reader from behind. But even as he does that time is passing. It cannot be spoken, for to speak it is to deny it; it can only be felt. (p. 29)

From Tristram Shandy in the first essay, Josipovici moves on to Shakespeare and a consideration of how time works in Othello in the second. The third essay wanders, starting with Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, spending time with Doctor Faustus, Proust, and T. S. Eliot, on through Dante, Borges, and Picasso. In this essay he wonders broadly about the question of quotation: how words can be (and, in a sense, have to be) borrowed from others. Language comes from others, like Lévi-Strauss’s axes; the modernist problem is partially one of finding one’s own voice in a sea of others. In the novel, this becomes the problem of separating the voice of the characters from the voice of the author:

But today, because we have at last realised that a work of art is not natural, like a horse, but part of a system of representations, like an axe, we can see that this notion of an artist or an author was a myth, perpetuated by a whole ideology of the subject. We know now that the artist is a maker. He puts his material together for the sheer pleasure of it, and any relation it may have with the real world is purely coincidental. A fortune-teller needs to know what the cards mean, says Robbe-Grillet, a bridge-player only how they are used. The artist is a player. (p. 91)

But Josipovici is uneasy with this definition and suggests a refinement:

What I have been suggesting today is that the modern artist, recognising the impossibility of speaking in his own voice, is indeed a maker; but what is important about his work is not that he makes an object, or plays a game, but the sense he conveys of the act of making itself. (p. 91)

The final essay, “A Bird was in the Room,” deals with Kafka’s final notes, texts that might not be linguistically interesting, but which the reader finds compelling because they are written by a man who was soon to die: we can’t help but impute meaning into gnomic statements like “A bird was in the room” or “A lake doesn’t flow into anything, you know” when put in that context. The notes possess authority because they are last statements: the death of the author gives them meaning.

This is a beautiful book, not so much because it makes an argument but because it’s a record of careful thinking which should be returned to. Trust is on my bookshelf; probably I’ll read that before getting to Whatever Happened to Modernism, descendent, in a sense, of this book.

september 26–september 30

Books

- John Crowley, The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines: A Story

- Jorge Luis Borges, The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory, trans. Andrew Hurley

Films

- Shanghai Express, dir. Joseph von Sternberg

Exhibits

- Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts

- “James Case-Leal: Radical Spirit,” Church of the Messiah, Greenpoint

- “Liao Yibai: Real Fake,” Mike Weiss Gallery

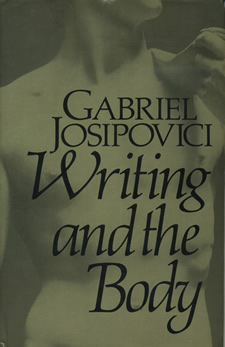

john crowley, “the girlhood of shakespeare’s heroines”

John Crowley

John Crowley

The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines: A Story

(Subterranean Press, 2005)

So I am slowly working my way through the back catalogue of John Crowley, and having read most of the major things, now I’m mopping up the rest. This is a short book, barely a novella; the text was originally published in Conjunctions 39, but this is a beautiful edition from the Subterranean Press, hard cover with a silver-foil stamped boards: it’s hard to resist picking up such a book, and I generally don’t. In Amherst for a few days, I bought too many books; this is the one I turned to first, though there are others I should be reading.

I like John Crowley’s work in part because it’s not quite clear how to pigeonhole him. Most obviously, a case could be made that Little, Big and the Ægypt books are fantasy, but an equally strong argument could be made for the opposite. This is usually discussed whenever Crowley’s work is discussed; maybe it accounts for his odd place in the literary firmament. In this book, another of Crowley’s characteristic traits appears: it’s nostalgia-inflected and there’s a layer of sentimentality, something that can also be found in the bigger books. Sentimentality, of course, is generally banished from serious literature as the enemy of rigorous thought. Crowley here (and elsewhere) seems to be deploying it as a tool in his arsenal: it’s an odd trick, with interesting results.

The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines starts out apparently as a nostalgia trip: recalling a fictitious Indiana Shakespeare Festival from the late 1950s when the narrator would have been in high school. Doing the math reveals that the narrator’s age would seem to be approximately the same as Crowley’s; but put that aside. The narrator is a young Shakespeare enthusiast; he is clearly going to fall for Harriet, another young Shakespeare enthusiast whose youth is also described. Things risk becoming precious: the narrator is a dreamer who gets the idea from library books that he would be able to create a Greek theater in his backyard. Fourteen pages in, however, we are jerked into the present moment: Harriet is 38, the year is apparently 1981, as a Bulgarian has attempted to assassinate the Pope. Harriet and the narrator are not, apparently, together. Harriet is a photographer, and the description of her method suggests that something else is going on:

But these photographs don’t disappoint that way. The happiness they give is a little pale and fleeting – half an hour to set up the camera and make an exposure (hurry, hurry, the earth’s turning, the light’s changing) and an hour or two to make a true print: but it’s real happiness. Since they’re made from paper negatives rather than film, they seem to Harriet not to have that look of being stolen from the world rather than made from it that most landscape photographs have; they are shyer and more tentative somehow. Not painting, no, but satisfying in some of the same ways. (p. 16)

This comes after a discussion of the disappointment of painting: Harriet painted what she saw, but the next day found the resulting paintings not to accurately reflect the world. But there’s a lot buried here: this consideration of how art fits into the world doesn’t mesh with the youthful idealization of Shakespeare-as-great-artist in the previous section. Something has happened, it’s clear; and we’re sent back to the Indiana Shakespeare Festival, where blooming young love pushes the middle-aged present of the protagonists to the background again.

Complication sets in with the arrival of a man, nameless, who delivers a lecture to the young Shakespeareans on how Shakespeare could not have written his plays; he suspects that Francis Bacon is the likeliest candidate. The speech goes on in detail: it seems to be an introduction of doubt. Young love blossoms; the bookish young narrator goes to the library and discovers the voluminous works of those who have doubted Shakespeare’s authority, starting with Delia Bacon and continuing through to the present. And then the book changes entirely: as the summer winds on, the narrator and Harriet are separately stricken with polio. The pastoral beginning can be read very differently, as the narrator sees the braces of the Baconian speaker from the present:

I’ve thought of those canes, since then, and those braces. I’ve wished I could ask about them. There are things in your past, preserved in memory almost by chance, that only later on, because of the course your own life takes, come to seem proleptic, to significant when other things don’t. (pp. 26–27)

Read a second time, this book functions very differently: it’s an account of the relationship of two people and a past that can’t be escaped. The festival’s production of Henry V, not the most obvious play, then makes sense, as does the follow-up of The Tempest. At the same time, there’s an aspect of the book – the anti-Stratfordian argument – which doesn’t quite fit with everything else. The narrator grows up to teach Elizabethan drama; he sidesteps the Shakespearean controversy, just as the academy does. Perhaps an answer can be found in the figure of Delia Bacon, whose quest to prove that Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare seems quixotic, if perhaps predicated on a life that didn’t work out as she would have liked. There is a romance to the anti-Stratfordians: their belief that the past contains a secret that could explain the present.

This is not, finally, a sentimental book: what seems to be pastoral is actually very carefully controlled by the narration. The title comes from an older book, by Mary Cowden Clark, seemingly an attempt to create backstories for Shakespeare’s heroines, perhaps that their behavior in the plays might be more comprehensible. One looks to the past for explanation.

The interior design of this book suffers a bit from the strange decision to use Zapf Chancery for the headers, with the resulting effect that it looks like it springs from the halcyon days when the Mac, Truetype fonts, and desktop publishing were brand new, a syndrome that might also be noticed in the lettering on Kate Bush’s The Hounds of Love, which had a somewhat more legitimate claim to the aesthetic, being released in 1985. What might possess a book designer to revisit that period twenty years later is beyond me, especially when the covers, done by another designer, are so lovely. It feels weirdly amateurish, the sort of thing you’d see in a church cookbook; and in its way it makes Crowley’s writing seem to be overly sentimental. It’s also strange that such attention would be paid to the covers while so little seems to be given to the interiors, though I guess that’s increasingly less surprising.

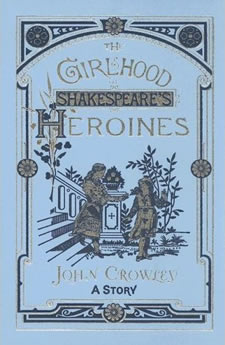

rejections

alice b. toklas, “what is remembered”

Alice B. Toklas

Alice B. Toklas

What Is Remembered

(Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1963)

Back to Gertrude Stein: though I’ve read her memoirs-as-cookbooks, I hadn’t previously gotten around to this, Alice Toklas’s memoir-as-a-memoir. The voice here is strange: it seems familiar, of course, from Stein’s imitation of it in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas where she’s describing many of the same scenes. This feels almost like an echo: at times its hard to tell if what the reader is receiving is a memory or a memory of Stein’s book. But it’s hard to tell where this voice comes from: Stein’s has been inflected on it, and sometimes Toklas’s is almost indistinguishable from Stein’s. Here, for example, is the last paragraph of of a chapter where Alice casually dismisses her roommate Harriet Levy’s religious crisis:

Sarah Stein now told Gertrude of her giving up the spiritual case of Harriet. They thought David Edstrom should undertake the case. David Edstrom was a good-looking young Swedish sculptor. He had not known anything like Harriet before, though he had known many American women in Florence where he had lived for several years. He soon told Gertrude lively stories of Harriet’s spiritual life. (p. 39)

That comma presumably wouldn’t be in Stein’s version of this paragraph: but the narration in the simple past tense slightly modified (“now told,” “soon told”), the generally simple sentences, the parallelism that begins and ends it (“Sarah Stein now told Gertrude,” “He soon told Gertrude”; “he had not known,” “he had known”) and repetitions (“David Edstrom”) and variations (“spiritual case of Harriet,” “Harriet’s spiritual life”) are familiar enough that one might almost think of this paragraph as a pastiche. But then a few pages later something like this appears, a voice which seems entirely different:

The winter commenced gaily. Gertrude during this winter diagnosed me as an old maid mermaid which I resented, the old maid was bad enough but the mermaid was quite unbearable. I cannot remember how this wore thin and finally blew away entirely. But by the time the buttercups were in bloom, the old maid mermaid had gone into oblivion and I had been gathering wild violets. The lilies of the valley, forget-me-nots and hyacinths we gathered in the forest of Saint-Germain were more delicately colored than those of California, which were more robust and even more fragrant. (p. 44)

There are differences in emphasis, of course: Hemingway only appears glancingly here, and there’s more Matisse and less Picasso. There are less celebrities in general: this is largely about Gertrude. Tchelichev is dismissed a sentence after he appears; but she will admit to liking René Crevel. The appeal of Francis Rose isn’t really explained here either. (“Georges [Hugnet] spoke slightingly of Francis. One did not blame him, Francis was a very difficult guest.”) And we do learn that though Gertrude never met Jane Bowles, she did meet Alice in Paris after Gertrude’s death. There’s surprisingly little about Stein’s books, especially in comparison to Stein’s memoirs. The American trip, fretted over by Stein in Everybody’s Autobiography, is here a complete triumph; World War II passes quickly, and Toklas’s account is close to Stein’s, if not quite as breathless.

Things do leak out, of course, that wouldn’t be in Gertrude Stein’s account: she wouldn’t mention, for example, that Sarah Stein became a Christian Scientist. Arthur Cravan shows up as “Craven . . . a very handsome Englishman who wrote a pamphlet on the salon paintings that caused a scandal and who boxed for pleasure” (p. 76). And there are minor revelations, like the appearance of this telephone:

After only a week in Paris, Ada returned to London and I went to the plays of Bernstein in which Guitry père performed. In one of them I saw one of the first portable telephones. Before that, they had always been attached to the wall. The audience buzzed with excitement as the curtain went up and revealed it. The acting was as brilliant as the lines. (p. 46)

Presumably what is being described is a table-top telephone; though of course a telephone wouldn’t seem to be particularly functional in a play, at one point it must have been new enough to cause excitement, something which must have seemed impossibly foreign in 1963. An anecdote which seems like it has to be related to Duchamp, though there’s precious little context for it:

[Miss Blood] asked [Picasso] what he considered his contribution to painting. He said, Je suis le bec Auer, a gas mantle. (p. 55)

I will assume that some assiduous art historian has tracked down the provenance of this quote and whether or not it has anything to do with Étant donnés.

And occasional moments of a relationship stand out: here, for example, Alice is made extremely unhappy by the weather at Saint-Rémy:

But Gertrude had written so well there, and so happily, and so much, that I made up my mind I would behave and not complain. (p. 122)

Here as elsewhere in the book there’s an enormous fealty to the figure of Gertrude Stein. After a perfunctory recitation of Alice’s life before meeting Gertrude, What Is Remembered is less an autobiography than it is a memoir of Alice’s time with her. The book contains a number of illustrations of Gertrude Stein in a variety of formats; there are plenty of photographs of the pair together. Only two photos in the book are of Alice alone; the first is one of a pair by Carl Van Vechten of her and Gertrude, the second by Ettore Sottsass (!), is of her alone in the rue Christine in 1951. The book ends precisely at Gertrude’s death in 1946, though it was published in 1963. There’s not as much retrospective analysis here as one might hope: the title doesn’t overpromise. The book functions as a counterpart to Stein’s three autobiographies: it can be read against those, perhaps as a corrective, but Toklas here seems uninterested in talking about anything else. It’s hard not to psychologize: clearly, this is a gesture of love, but there’s a self abnegation that’s almost too much to take.

in the penal colony, again

“And here, almost against his will, he had to look at the face of the corpse. It was as it had been in life; no sign was visible of the promised redemption; what the others had found in the machine the officer had not found; the lips were firmly pressed together, the eyes were open, with the same expression as in life, their look was calm and convinced, through the forehead went the point of the great iron spike.”

(Kafka, quoted in Gabriel Josipovici’s Writing and the Body, p. 114.)