Jane Bowles & Denton Welch

Jane Bowles & Denton Welch

A Stick of Green Candy

(illustrated by Colter Jacobsen)

(Four Corners Books, 2010)

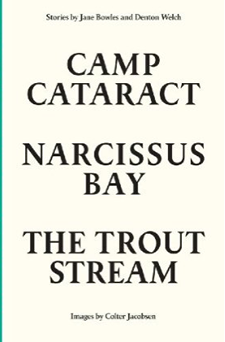

This book is not, of course, a long-lost collaboration between Jane Bowles and Denton Welch; rather, it consists of two stories by Bowles (“A Stick Of Green Candy” and “Camp Cataract”) and two by Welch (“The Trout Stream” and “Narcissus Bay”) will illustrations by Colter Jacobsen as part of Four Corners’s Familiars series, where artists are invited to illustrate texts. Four Corners make beautiful books: this is hard-cover, beautifully bound, with attention paid to details: the white case has a shiny green spine, candy-like enough. The title page is hand-lettered; the illustration is generous, not only black and white but also full color. Matthew Carter gets thanked on the colophon for his work on the type; the book was printed in Italy. Four Corners makes books for people who appreciate beautiful books, and this is a large part of the attraction of this edition. There’s something to be said for this assemblage of stories, though. The Jane Bowles stories are in print, as part of My Sister’s Hand in Mine. The Denton Welch stories are a bit harder to get ahold of, at least in this country: Tartarus Press put out a complete edition in the U.K., but it’s pricey and I don’t have a copy of it. I probably should.

The illustrator, Colter Jacobsen, seems to be the person who selected these stories to appear together. What ties them together, besides his judgment? Though the writers were roughly contemporaneous, they’re very different; while Welch’s works tend to be strongly centered around a single consciousness, it’s pointedly difficult for the reader to find anyone to identify with in the work of Jane Bowles. Three of the four stories here involve strange children; the fourth, “Camp Cataract” is about two sisters whose relationship never quite becomes adult. In “The Trout Stream,” Welch’s protagonist young protagonist observes his elders, who try and fail to make themselves happy; in “A Stick of Green Candy,” a young girl, ignored by her parents, grows up by herself. “Narcissus Bay” relates the story of a young boy in China who sees a procession of a beaten woman, two chained men, and a police officer, the aftermath of some crime; more importantly, he learns how his knowledge of this can affect those around him. Like “The Trout Stream,” “Camp Cataract” seems to end with a drowning. If Bowles and Welch’s voices aren’t particularly similar, there’s a consistency to these stories in their focus on outsiders. Welch’s narrators seem to be outsiders by choice; those of Bowles seem dragged along by the world around them.

I like this presentation: with only four stories, these narratives have room to breath, and the reader is encouraged to slow down. The Bowles stories can be found in the FSG collection of her works; to my mind, though, they suffer in that context from being presented after Two Serious Ladies, a more powerful work. Welch’s stories appear with 74 of their fellows in his collected stories; I know that I find it hard to focus on details in the midst of so much. Here details stand out: at the country house of “The Trout Stream,” they eat Bombay duck; later, a woman has a “voice like an electric guitar”. I don’t know when the story was written, but Denton Welch died in 1948; one wonders what that sound would have meant to him. There’s something to be said for having the leisure to appreciate this; certainly its possible in a collected work, but it’s more difficult.

Colter Jacobsen’s illustrations appear to be pencil versions of found photographs: snapshots of children playing at dusk, people in front of old buildings, some men behind an enormous shark. Most of them are repeated: one image on the left page, one on the right, though there’s not a precise repetition: small differences can usually be discerned between the two images. The images in the endpapers (a waterfall with a slight rainbow, done with colored pencil as are a handful of other images in the book) appear to be mirrored across the gutter, but looking more closely reveals that the left and right images, though similar in outline, are entirely different in detail: the rock face and trees are entirely different. Some of the drawings of photographs give the impression of having been manipulated or treated: in the pictures of the men with the shark, the shark seems to have been whited out or erased.

One spread shows two snapshots, dated “4-1941”; they are again imperfectly mirrored, and in one of the photos, depicting two women, the faces are blurred on the right: there’s something almost creepy to this. There isn’t generally anything that directly ties the illustrations to the text; there’s a similarity in feeling, however, and the reader comes away with the idea that like the depicted photographs, the stories have also been rescued from the past. With this spread, the last set of paired photographs in the text, it’s possible to draw a correspondence between what’s pictured and the story that’s being illustrated (“Camp Cataract”): there are two women who might be the sisters of the story, a date which might match the story, a label (“COLD SPRING – N.Y.”) which might fit the story, and two images of waterfalls, one of which appears prominently in the story. This set of images most directly matches the text; flipping back through the text of this particular story, one can find other illustrations which also fit, as well as some that don’t (a reproduction of a color photograph of a small girl holding up a piece of clothing; a teenager in a B.U.M. t-shirt inhaling from a bong): these weren’t drawn from Bowles’s text, but they feel of a piece with the text.

There’s no artist’s statement with this book: I would have liked to see one, as the choices made here are interesting and not obvious. John Morgan is the designer of the series; I feel like I should go back and get the older books in this series.