“There are few differences among filesystems; most closely follow the Unix model. And alas, one of the few innovators in filesystem design is now in prison for murder.”

(Ted Nelson, Geeks Bearing Gifts: How the Computer World Got This Way, p. 62.)

“There are few differences among filesystems; most closely follow the Unix model. And alas, one of the few innovators in filesystem design is now in prison for murder.”

(Ted Nelson, Geeks Bearing Gifts: How the Computer World Got This Way, p. 62.)

Movies

Exhibitions

Books

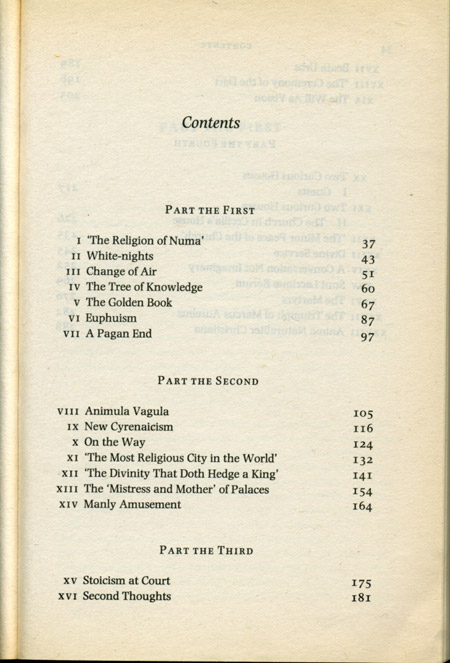

(Walter Pater, Marius the Epicurean, Penguin, 1985.)

The third edition of My Voyage to Idaho has been published. Still not worth buying. But: you can download a screen-formatted PDF here, which now includes PDF hyperlinks and a working table of contents.

The second edition of My Voyage to Idaho has been published. Rather than buying it, you can download a screen-formatted PDF here. Someday this will improve, but not yet.

Because we don’t have enough unfinished projects around here, here is another one: Locus Solus Editions. Using Lulu, I intend to keep publishing the same book, provisionally titled My Voyage to Idaho, until it is finished or can be left definitively unfinished. The first edition is up at Lulu; you can download a screen-readable PDF here. I wouldn’t bother buying it.

After an extended absence, Locus Solus Industries returns:

(apologies to Designers Republic.)

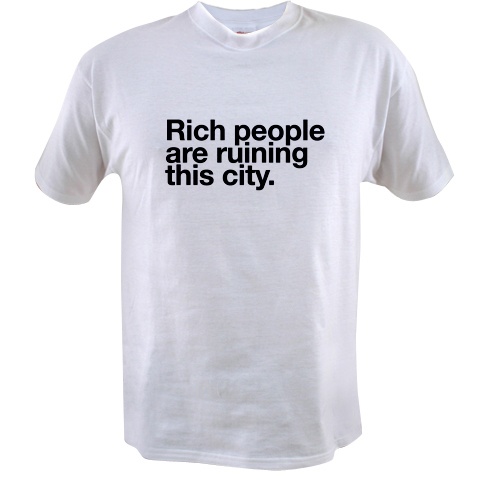

Belatedly, a shirt for wearing to immigration protests:

Also, one can’t help but note that the Spanish slogan for the marches is much better than the English one (squint to see it in the picture): in English, one is asked to love the abstract “Immigrant NY” while in Spanish we love the more concrete immigrants of New York:

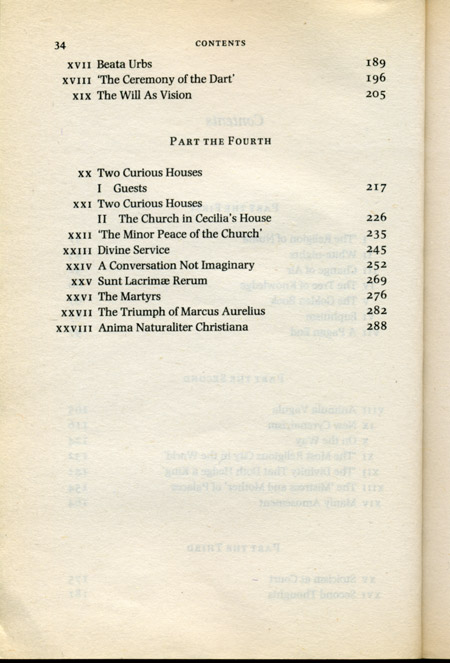

No. 11 is a shirt for the disaffected youth one hears so much about these days. It looks like this:

And that is all I have to say about that.