- Nicolas Carone has died.

- I wrote a piece about sitting with Marina Abramović for a Tumblr project someone’s putting together.

- The Book Depository’s live map is entrancing, though everyone else has noted that by now.

tom rachman, “the imperfectionists”

Tom Rachman

Tom Rachman

The Imperfectionists

(The Dial Press, 2010)

My friend C. sent me this book as a gift; several years ago, we wrote a travel guide to Rome together, and she had thought this book, written about a former AP staffer in Rome about a newspaper in Rome, might be interesting. She didn’t love it; I’d noticed the reviews and thought the book might have potential, even though the wrong sort of people were liking it, but after flipping through it in a bookstore I was confident that it wasn’t a book I needed to buy in hardcover. It’s nice to be sent a book as a gift, especially a book that someone has already read and marked up with their displeasure; there’s something nice about reading a book that you know you’re bound to dislike, figuring out exactly why you don’t like it.

What might be most interesting about this book is its structure: it’s constructed from 11 short stories, each given the title of a news story (a strategy that ends up coming off as a gimmick) and a subtitle with the name and position of a person who works at an English-language newspaper based in Rome which will close by the end of the book. Each story is relatively self-contained; there’s chronological progression through the stories, though they seem to happen from around November 2006 to around April 2007, dates which can be pegged by the news stories. Each story is told from the third-person perspective of a different character; characters recur, and complete stories can only be constructed by reading more that one story. This straitjacket approach to structure doesn’t always work; some characters are more extraneous than others (a judicious editor would have cut at least two and possibly three chapters) and a couple of major characters don’t get their own chapters. The success of such polyphony is decidedly mixed: the voices of the women, in particular, seem cartoonish – women in positions of power, for example, turn out to be vicious harpies with unsatisfactory sex lives – and the character that Rachman seems to be having the most fun writing, a veteran scoundrel reporter named Rich Snyder, is the most tangential to the greater narrative.

Each chapter concludes with a separate section, set off in italics; these report the history of the newspaper, starting with the newspaper’s founding in 1953 and moving into the present to converge with the main narrative at the end of the book. The newspaper itself would be the main spine of the book; this isn’t, however, as compelling as the people around it. At the end of the book, one of the characters has the intention of writing a history of the newspaper; but this history, we are told, is never started, and the italicized history is from an omniscient third-person perspective that is not his.

The book’s structure suffers from being similar to Georges Perec’s Life A User’s Manual, which also tells interlocking stories from multiple perspectives; Perec’s book constrains itself to a specific moment in time rather than a series of instants, as this book uses. Finishing Perec’s book, one feels compelled to go back to the beginning, to re-read the narratives, knowing how they will turn out; here, one notices clues, but the overall narratives aren’t enough to compel re-reading: one doesn’t feel that any more secrets are likely to reveal themselves.

My disappointment with the book os partially personal: having lived in Rome, though not during those particular years, I expect a certain amount of local color, something that should be possible. Unfortunately, this book seems to be set in Rome almost at random: there are details here and there, but the story could be uprooted and moved to Paris or Brussels without much trouble: cartographic details would need to be changed, but the overall structure (and almost all of the characters) of the book could remain exactly the same. Most are Americans in Rome; they don’t behave so much like ex-pats in Italy (a type that could be carefully delineated) so much as they behave like American characters, uprooted from America by authorial whim. A sulking character, for example, shuts herself up in her room and starts shoveling down Häagen-Dasz. It’s possible that American brand is now available in Italy; but almost certainly Americans in Rome are still likely to go on and on about how superior Italian gelato is than any American version. A surprising number of Romans love ice cream cones from McDonald’s; ex-pats go on and on about cultural imperialism. Italy seems to have little effect on these characters; some have the requisite Italian boyfriends and girlfriends, but nothing is learned from them. This is, of course, a purely personal complaint: the author has no duty to gratify me by making this book about what I want it to be about, even if that is more interesting and would make it a better book all around. There are a number of solecisms in the book, some of which might be attributed to a lack of a copyeditor familiar with what Rachman is talking about: “Fiumicino Airport” is not, for example, a proper noun but rather the town where Leonardo da Vinci International is located. But again, these mistakes aren’t likely to annoy most readers.

The biggest problem with the book, and one that might be related to its carelessness with setting, is how it strains credibility. I don’t have a problem with the rejection of conventional realism, of course; but this is a book which is using realism as its mode. (One exception, which triggered my earlier comparison to Life a User’s Manual: one character is a reader of the paper who has been making it her business to read everything in the paper, every day, with the consequent result that her chronology slips further and further from that of the outside world; finally, when she is missing a single issue, it breaks down entirely. But this is the only prominent instance of fabulism in the book.) When a book proceeds by realism, the reader losing faith in the book suggests a problem with the book. The premise of the book is that a billionaire sets out to run a world-class English newspaper out of Rome: this is problematic. Rome isn’t a place that anyone with a modicum of sense would think to do this; even limiting choices to Italy, it would make much more sense to work out of Milan, and if one were trying to get things done it would make much more sense to leave Italy entirely. Starting a major newspaper in Rome, romantic as it may sound, is somewhat akin to the idea of starting a major American newspaper somewhere like Albany. The reader wonders as well when it turns out that the newspaper doesn’t have a website. This might be believable if the book were set in 2000 or if the newspaper had some sort of specialist slant resistant to the Internet; when the paper seems to be modeled on the International Herald-Tribune and the book is set in 2006, when American newspapers were already on the point of collapse, it defies all belief, especially when this turns out to be a large part of the reason the paper collapses. That’s just not how businesses are run. One might suspend belief if there seemed to be some good reason for it, the setting, perhaps; but it’s not there.

ettie stettheimer, “love days”

Ettie Stettheimer

Ettie Stettheimer

Love Days

(in Memorial Volume of and by Ettie Stettheimer)

(Alfred E. Knopf, 1951)

Love Days, originally published under the pen name Henrie Waste (from HENRIEtta WAlter STEttheimer), has the strange full title “Love Days [Susanna Moore’s],” Susanna Moore being the protagonist; perhaps another Love Days had been recently published in 1923 and this was to avoid confusion. The Stettheimer sisters were friends of Marcel Duchamp in New York; this novel features a character based on Duchamp, which is my reason for picking up the book; his correspondence with Ettie Stettheimer suggests that he found the portrayal amusing. His correspondence with the Stettheimer sisters, and particularly Ettie, was one of his most sustained; I’ve seen her sister Florine’s paintings, some of which feature him, and Carrie’s immense dollhouse, now at the Museum of the City of New York featured a tiny version of Nude Descending a Staircase that he made to order. Ettie Stettheimer’s writing, however, seems to be neglected.

The book is presented from the perspective of Susanna Moore, a New York orphan who seems to be of considerable means, though that’s never quite explained. The book isn’t a roman-à-clef, though Duchamp appears rather transparently as the figure of Pierre Delaire; nor is he the only famous figure to appear in the book, as Maxim Gorky has a role as an extra in Capri, and a Cubist painter couple might be meant to be the Delaunays. The book follows Susanna Moore, first through Barnard, then studying in Germany; thus far, it might be said to follow the life of Ettie Stettheimer, who earned a doctorate in philosophy at Freiburg in 1907. She then returns to New York, where she sets herself up as an independent scholar of Greek; after soundly rejecting men for most of the book, she very suddenly falls madly in love with Grodz, a French painter of Finnish-Greek extraction, and marries him. Ettie Stettheimer, like her sisters, never married.

As far as I can tell, this volume is the most recent publication of Ettie Stettheimer; there doesn’t seem to be much interest in her prose. This particular volume is a bit macabre: evidently after her sisters Carrie and Florine died and Ettie had put their affairs in order, she decided to provide for her own posterity by putting together this omnibus edition of her own work: this novel, an earlier novella (Philosophy: A Fragment, about an American girl studying philosophy in Germany), a philosophical work that had been her dissertation on the work of William James (which seems to have been her most widely read work), and four short stories. She adds an introduction to the whole; a few contemporary reviews are inserted as introductions to the individual volumes. The Memorial Volume was published by Knopf in 1951; nonetheless, this has the slightly sad feeling of a vanity project, right down to the dedication, to “E. S.”.

This isn’t the most likable novel; at 350 pages, it’s probably twice as long as it needs to be, and fifty-page chapters are tiresome. The characters are predictable: the overly romantic French artist that she marries almost immediately is filled with jealousy before the honeymoon is over. Stylistically, there’s a rather excessive use of ellipses, designed to indicate emotion; there’s sometimes something about the writing that seems off.

Susanna folded the letter and gurgled. She gurgled when she laughed to herself and felt apologetic for finding herself amusing. (p. 62)

This gurgling is a one-time affair, but she is given to drawling, even in German. Later, when the heroine considers Ewart, an American she meets in Capri when he offers her a powder for a headache of convenience:

She decided that he looked like a smart twenty year old lounge lizard, and like a forty year old scientist, and she was pleasantly intrigued by the unresolved combination he presented. (p. 187)

This description is good enough for a reprise thirty pages later:

Ewart, the considerate and objective young lizard bulging with a brow that seemed a temple of wisdom, was saying, “Of course it has been proved statistically that the great majority of marriages are unsuccessful; one member is unfaithful to the other, which is probably perfectly natural, since according to psychological law people grow tired of anything after a time, etc. etc. . . .” (p. 216)

Susanna Moore’s marriage does collapse and end in divorce, though the actual collapse happens in a gap between chapters; it is blamed on pneumonia. While recovering from the pneumonia in a sanatorium, she first encourages the attentions of a Nietzscheian baron; then she finally finds love in the person of a English doctor who is the baron’s wife’s cousin and reputed lover but who has tuberculosis. This isn’t quite as interesting as it might sound: plot twists are telegraphed well in advance and the characterizations and varied geographic settings (hotels in Europe, mainly) aren’t particularly interesting.

Susanna Moore seems, on the whole, rather full of herself and a bit tiresome. On the whole, she appears lacking in feminist consciousness; but there are strange passages that suggest that she might be more interesting. While she’s in her Greek class at Columbia, one of her friends, whom she dislikes, suggests that she should get married and settle down with children, a suggestion that Susanna has no truck with:

”No,” Susanna said in her languid way that never sounded final, but often was.— Whenever her potential motherhood, marriage or death were touched on in conversation she felt as though some one else were being referred to, and the chief emotion produced in her was one of estrangement from the speaker who so unpleasantly identified her with that other person. . . . “Let’s go on with Medea. She got married and didn’t settle down to a hum-drum existence,” she remarked, feeling much closer to Medea at this moment than to Blanche. (p. 17)

Frustratingly, this isn’t elaborated on; this is also the case later in Germany, where she complains to a would-be swain that she thinks is odd that an elderly German man should be explaining Sappho to her; then she asks Tom to explain what he thinks of Sappho, which isn’t much more helpful:

”In other words, because she made great poetry of perverse love, she must have been perverse?” she asked.

“Felt perverse, anyway.”

“And,” Susanna continued to educate herself, “why was she perverse; because she had no adequate normal love affair, did you say?”

Tom burst out laughing. “You seem to regard me as an authority, you funny Susan, or are you trying to find out something else? I wasn’t there, you know; I mentioned this as a probably cause of perversity: often men and women are driven to perverse practices because the normal satisfactions obtainable are of an unbeautiful nature, more unbeautiful than the perverse ones seem to them at any rate to be. This is the most favourable interpretation of perversity, reserved for artists and people who seem to have some pretensions to a sense of – of fastidiousness.” Tom paused; he had seen Susanna’s face frowning like a perplexed child’s trying to understand. His strident voice grew softer. “All in all, my dear, it’s not an attractive subject, and it’s hard for healthy people to grasp, so don’t be alarmed if you don’t ‘get’ it; neither does the Professor. Susan, child, where are we going?” (p. 70)

With that, the subject is dropped entirely. It’s vexing, because there is obviously an interesting subject here; but again it’s simply pushed aside. While in Germany, she is pursued by countless lovelorn Germans, a romantic people; she wants none of their attentions, and realizes that she can escape them by saying Mir ist schlecht, I feel sick. There’s an echo of this at the end of the book: Hugh, her English doctor, is the perfect object for her love because he is sick, and loving him will make her sick. He refuses; she seemingly kills herself by covering her mouth and holding her breath. It’s a bit too clumsy to be affecting, and Susanna Moore isn’t quite a model feminist: but the novel does provide a picture of a woman trying to make her way through an uncomprehending and unjust world.

The character based on Duchamp has a walk-on part; he visits her once, and stays for five pages. Susanna Moore appears to have no real friends; a few appear, but each is jettisoned in their turn. Pierre Delaire seems to be the only one to escape this. He isn’t a romantic figure to her: she thinks that “his delicate fairish classicality of a dry and cerebral quality had all of beauty except beauty’s particular thrill” (p. 95) and he disappoints her by having shaved his head. He explains his new canvases:

”In form Cubist – but there is an ulterior intention which removes them from Cubism. I wanted to produce those impressions so painful to the eye which it sometimes receives from a moving picture when several objects more simultaneously at different velocities, – for instance in the picture of a race. Do you remember that we once saw one together and remarked on it? The eye became confused and the head a little dizzy. Eh bien, it interested me to get these same effects through static means.” (p. 96)

Susanna Moore refused to take voyages with Delaire, just as Ettie Stettheimer refused to set sail for Buenos Aires with Duchamp; Moore and Delaire fall into a discussion of their lives as a solar system, a mythologization which might, at a stretch, be seen to reflect Duchamp’s myth-making in the notes for The Large Glass. And then he wanders out of the book: he doesn’t seem to have missed much.

noted

- My interview with Bob Stein is up at Triple Canopy as part of Issue 9.

- A thread at MetaFilter about Jack Green’s Fire the Bastards!. Tangentially related: David Markson’s library appears at The Strand; some of his Gaddis annotations have appeared online.

- Gary Shteyngart & Joshua Cohen on the Tablet podcast.

- More of Robert Walser’s poetry is coming out in English.

- Joseph McElroy’s Preparations for Search is available from Small Anchor Press; the text was originally published in Formations in Spring 1984 as part of Women and Men, but cut before that book’s publication; Small Anchor’s edition has been “slightly revised”.

- Trevor Winkfield, Miles Champion & Steve Clay present “Poems and Pictures: A Renaissance in the Art of the Book (1946–1981) tonight at 6:30 p.m. at the Center for Book Arts.

- Tomorrow: a release party for Tan Lin’s Seven Controlled Vocabularies at Printed Matter from 5–7.

- Also tomorrow night: Ferry Radax’s documentary Thomas Bernhard – Drei Tage shows at Anthology Film Archives at 7:15 p.m. Also shows on Friday at 9 p.m.

frederick rolfe, “the desire and pursuit of the whole”

Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo

Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo

The Desire and Pursuit of the Whole: A Romance of Modern Venice

(Cassell & Company Ltd., 1951; first published 1934, written 1909.)

This book gives the reader pause from the first sentence; following an epigraph from Plato, we learn:

The text chosen, o most affable reader, on which to hang these ana of Nicholas and Gilda for your admiration, will require such a lot of expounding that we must get at the heart of explanations (as to how it all happened) without undue delay.

And we’re off and running. “Ana” is not a misprint; nobody writes books, or uses the English language, quite like Frederick Rolfe did. Baron Corvo, as Rolfe also presented himself, is best know for Hadrian the Seventh, in which a down-on-his luck Englishman becomes Pope; Rolfe’s rather odd life – he was repeatedly foiled from his attempts to become a priest – suggests that this plot was wish fulfillment. The introduction of this book, by A. J. A. Symons, Rolfe’s first biographer (The Quest for Corvo) presents this book as being a further fictionalized autobiography. On reaching page 36, where the many affronts against the life of Nicholas Crabbe to that point have been narrated, the reader is confronted with a footnote, presumably by Symons:

Readers of The Quest for Corvo will need no telling that Rolfe is following the lines of his own life very closely in the description he gives of Nicholas Crabbe’s career. Peter of England is Hadrian the Seventh, Don Superbo is Don Tarquinio, Sieur Rènè is Don Renato, and Songs of Gadara represents Songs of Meleager.

At the bottom of the next page, another note:

Here again Rolfe is, of course, drawing from life. “Bonsen” is the late Mgr. R. H. Benson; and The Sensiblist is The Sentimentalist, a novel which aroused much discussion when it was first published. The central character, Chris Dell, was in some part drawn from Rolfe.

(The annotator commits a solecism: Benson’s book is The Sentimentalists (1906).) It’s hard, when there are such footnotes, to avoid reading this book as a roman à clef: Nicholas Crabbe, Rolfe’s hero, is beleaguered by the world to such a degree to put any modern novelist with a blog to shame. Here, for example, is described the double of Robert Hugh Benson, who seems to have been an inoffensive Catholic novelist who, Symons reports in his introduction, tried to help Rolfe by giving him work but drew his ire by refusing to pay his excessive hotel bills in Venice:

The Reverend Bobugo Bonsen was a stuttering little Chrysostom of a priest, with the Cambridge manners of a Vaughan’s Dove, the face of the Mad Hatter out of Alice in Wonderland, and the figure of an Etonian who insanely neglects to take any pains at all with his temple of the Holy Ghost, but wears paper collars and a black straw hat. (p. 36)

Crabbe and the narrator of this book are Catholic (with the zealotry that only the convert can muster) and vitriolic in equal measure, which is a great deal of the pleasure of this text. The story being told is insane; but Crabbe constantly has recourse to the logic of the Church (as he understands it) to back up his logic. The Church, of course, rejects him entirely (he would have been a priest but was blackballed); but that might be to be expected as he is holier than the Church. If only he were Pope, of course, these problems would be solved; but things aren’t so easy:

Beside, he had published a book of personal experiments with priests, Peter of England, an awful audacious book which flayed whom it did not scald; and his mood was not to compete for reprisals. ‘It is not I who have lost the Athenians; it is the Athenians who have lost me,’ he superbly said. So, when priests slank up to him, he civilly warned them off: if they merited kindness and persisted, he gave them double: but, never any more would he admit them beyond the barbican of his lifted drawbridge, never any more would he go beyond parleys from the height of his impregnable battlements – unless they should come, at high noon, with a flag of truce and suitable gages – never any more would he on any account seek them, but to serve him as ministers of grace. (pp. 60–61.)

Crabbe goes to Mass every day, denounces the local Anglicans as Erastian heretics, and quarrels with almost every priest he meets. What’s most surprising in this book, though, isn’t Crabbe’s love/hate relationship with Catholicism (a continuation of Hadrian the Seventh) but its bizarre treatment of gender. Crabbe, sailing alone in the Adriatic Sea, rescues a young girl, her village’s only survivor of an earthquake; but Crabbe is aghast with the impropriety of being along on his boat with a woman. His solution is to declare the androgynous Zilda (the Venetian abbreviation for “Ermenegilda”) to be a boy, Zildo; the girl is more than happy to go along with this, and for the rest of the book, she is a he, with the odd lapse, happily playing the role of Crabbe’s manservant and straining dictionaries just like his master when he’s not speaking in Venetian dialect:

‘I do not understand why this eximious Signor Caloprin will pay me thirty-five franchi every Monday at 8 o’clock, and also a hundred more at 8 of every fourth Monday, just for writing my name.’ (p. 111)

What Crabbe feels for Zildo certainly seems to be love; but it’s a love that Crabbe doesn’t seem to know what to do with. He moves Zildo into a remote apartment so that they might not always be seen together; but Crabbe seems to avoid Zildo, who nonetheless remains devoted. In a moment of crisis, Crabbe considers desperate options, including finding a wife with money:

O god of Love, never! Infinitely far better to marry not-Zildo – if not-Zildo would. But – would not-Zildo? Well, why not? ‘He, who dispenses with woman, lives in sin.’ said Maimonides. (p. 178)

This doesn’t happen; Zildo and Crabbe continue to keep their distance. At the end of the book, however, there’s an odd turnaround: Zildo rescues Crabbe, who is dying of starvation in her boat; when Crabbe recognizes that Zildo has saved his life, he suddenly declares Zildo to be Gilda, and they are in love. This final sex change happens two pages from the end of the book; they appear to be on their way to get married, as Zildo/Gilda has arranged things with the local priest. A check arrives; there’s a happy ending.

It’s hard to know what to make of this. One would certainly be inclined to read Crabbe as being gay: he huffs and puffs about how terrible women are; he moves Zildo to other quarters because he feels tempted by him; he describes young men in loving detail. Crabbe claims to have been chaste for the past twenty years, as he had intended to take Holy Orders; he seems to regard the priesthood as a homosocial paradise, but one that won’t accept him. He and Bonsen have their own private quasi-religious order (at least until Crabbe angrily resigns); at one point, Bonsen writes him about the advisability of recruiting Italian naval officers.

There’s a monstrous solipsism to this book: it is a record of the genius of Nicholas Crabbe, and its world is seen entirely through his eyes. A first-person narrator occasionally raises his head to reveal himself to be wholly in awe of Crabbe: “Despite his peculiarities, there’s no denying that Nicholas Crabbe was a man of insight and intelligence: though I admit that there is a great deal of difficulty in making this point clear, seeing that he entered into such very close relations with priests and Scotchmen.” (p. 141) One suspects that this narrator is Crabbe himself, at a later date. Zildo, the novel’s second character, exists almost entirely through the eyes of Crabbe, who has been allowed to determine his character down to the level of gender; maybe this could be read as metafiction, though this book doesn’t seem particularly self-conscious in that way. Everyone else barely exists; they are an enemy of Crabbe or insignificant.

The book is not without considerable flaws. Its misogyny (on the part of both Crabbe and the narrator) has been pointed out; as might be expected, there’s also casual antisemitism. The writing also has curious faults. In the second chapter, it’s pointed out that Crabbe is astrologically a Cancer; there follows an extended metaphor about his crab-like nature, and throughout the book he is constantly said to be rearing up, crablike, or “clashing his awful claws” or his “portentous pincers.” He is frequently furious because it is his nature. This becomes tiresome extremely quickly, not least because of how weirdly clumsy it seems: “He was still Crabbe, and as crabby as ever: but he began to exercise his crabbiness in directions which he had never tried or cared to try.” (pp. 155–6) I can’t tell what Rolfe is trying to do with this; maybe this is an attempt at humor that hasn’t aged well, but it can hardly be imagined that this would ever have been that funny, aside from the initial passage, directing the reader to boil and dissect a crab if they would know the true nature of those born under the sign of Cancer. Likewise tiresome is the subject of the writer complaining about his financial situation and the failure of his publishers to pay him; Crabbe’s vitriol is entertaining, of course, but the pecuniary detail is grueling.

But this is a lovely book if only for the diction: “cagotism,” “latebrose,” “dedecorous,” “physidoyls,” “vexilla,” “amoenely,” “succursale,” and the verb “ostends” (to pick largely at random) aren’t words one runs into every day. Rolfe’s English is glossed with Venetian and the occasional Latin; it would be hard to confuse a page of this book for that of any other, even one of Rolfe’s. In no other book, for example, is a servant likely to declare that “He preached so long, sir, that Mr Barbolan went to bed and left him; and Little Peter and Parisotto took him home, at 2½ o’clock, preaching imbriagally all the way, so that a vizile followed them” as one does on p. 208 of this book. And it’s hard not to like a book filled with imponderabilia like this: “Truth is tarter than taradiddles; and nothing is tarter, terser, than truth on the track of tired trash in a trance.” (p. 157) A copy of Don Renato, his book that includes a glossary of the macaronic language of Italian, Greek, and Latin in the back is waiting on my shelf: it’s tempting.

july 16–july 20

Books

- Jane Bowles, Two Serious Ladies

- Stanley Crawford, The River in Winter: New and Selected Essays

Films

- Big Top Pee-Wee, directed by Randal Kleiser

- American Splendor, dir. Shari Springer Berman & Robert Pulcini

Exhibits

- “Richard Diebenkorn in Context: 1949–1952,” Leslie Feely Fine Art

- “Off the Wall: Part 1—Thirty Performative Actions,” Whitney Museum

- “Christian Marclay: Festival,” Whitney Museum

- “Jill Magid: A Reasonable Man in a Box,” Whitney Museum

- “Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield,” Whitney Museum

- “Christian Marclay: Festival,” Whitney Museum

- “Facing the Artist: Portraits by John Jonas Gruen,” Whitney Museum

- Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York

stanley crawford, “the river in winter”

Stanley Crawford

Stanley Crawford

The River in Winter: New and Selected Essays

(University of New Mexico Press, 2004)

A consequence of growing up in the rural Midwest is a sort of pragmatism when considering art. This isn’t a pragmatism that Peirce or James wouldn’t recognize; rather, it’s a need to know what something’s good for, if anything. There are two causes of this: first, an environment in which art doesn’t exist as a matter of course; and second, the Midwesterner’s deep-seated belief that they are normal. I left the Midwest a long time ago, but I still find this attitude in myself from time to time; I’m not very good at appreciating architecture, for example, in no small part because the buildings that I grew up with were functional and nothing more. It’s an attitude I find in my reaction to reading as well: wondering who would read anything comes naturally when you grow up in an environment where no one reads anything. Obviously, the Midwest is not a yardstick against which anything should be measured; but it’s hard to step outside yourself.

There’s thus something that I find reassuring in Stanley Crawford’s writing: a sense of balance between art and work. Crawford’s fiction doesn’t appear to have reached a very large readership, which is a shame, as he’s a fine writer: his novels are modest and have been spaced out across forty years, but each is distinct and inventive. In his non-fiction – Mayordomo and A Garlic Testament – a philosophy becomes more apparent. Crawford makes a living as a garlic farmer in New Mexico; it’s an occupation that he’s put as much thought into as his fiction. Crawford’s someone who’s thought a great deal about how he and his writing fit into the world: I find this easier to stomach than the Monsieur Teste-like figure that most contemporary writers cut. This isn’t the most reasoned response; it’s more instinctual than not, but it is there.

The River in Winter is not the sort of book of essays that one expects from a fiction writer: only one of the essays in this book, “The Village Novel,” has anything to do with fiction writing, and even there Crawford is oblique (his “village novel” is metaphorical rather than a book), pointing out that living successfully in a community (in his case, Dixon, New Mexico) largely precludes writing about it:

Writers who grow up hearing episodes and chapters of the village novel at the knees of parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles set out into the literary world with something far better than a formal education – but this is also the source of the grief they can suffer when they offer up the contents of the village novel as a real book, a novel. They will then be charged with betraying confidences and appropriating something that belongs to no one person, or for quite simply getting it all wrong. (p. 146)

Crawford’s concern in this book isn’t writing; rather, it’s about figuring out how to live. He adopts a “small is beautiful” stance, following E. F. Schumacher; he observes the natural world around him and the way that people live in it. A third of the book has to do with water, as did Mayordomo, his chronicle of his time spent running a community irrigation ditch; while that book was concerned with how one particular ditch was run, here his eye roves, considering the myriad forces at play controlling water rights (especially the longstanding water adjudication batter) in northern New Mexico:

The ultimate effect of the adjudication process is to allow land to be separated from water, with complex consequences at the local level . . . . I have long argued that the fatal flaw of the adjudication process is that it allows the “commons value” of a water right to be privatized away and dissipated. Much of the commons value of water resides in the acequia system, which conveys the water from the river to the individual landowner. When that landowner is allowed to sell off his water right, he is also selling something which does not properly belong to him as an individual property owner, in the form of that portion of a commons which until then has underpinned and sustained the equity of his property as land and water. (pp. 69–70)

Crawford is talking about northern New Mexico’s idiosyncratic system of water distribution from his perspective as a small farmer; but he’s also aware that he’s suggesting the broader situation that all of us are in, a world increasingly full of reifications. While Crawford is too polite to make this a political book, his politics are apparent; as is a clear sense of morality. Comparisons might be drawn to Lewis Hyde; but Crawford seems to be more interested in people than in art. Later he considers the role of the funeral in his village and how we treat death in general:

Perhaps one of the reasons people leave villages all over the world is that they want to live in places where the lesson is not so relentlessly taught. Suburbs are places without graveyards, without necropolises. They zone out the dead. Like garbage and sewage, the dead are ferried away to special ghettos elsewhere – or anywhere. The modern liberal solution of scattering ashes to the wind seems to solve the problem nicely. By making the dead disappear in a puff of gray ash, we can conquer death itself. (p. 152)

It’s not all doom and gloom, of course; a number of these essays are attentive to the physical world. He considers the mud floor of his house and the apple crates that he’s reused for years in a manner not entirely dissimilar from Francis Ponge; but his is also an interest in human use and how we shape objects and the environment in which we live. His mud floor:

There are times when I have fretted over the unevenness of the floor, but in repairing it again last summer I realized that under our wear and tear it will continue to evolve in ways that other surfaces within the house will not, surfaces that will be recovered, smoothed down, painted over, again and again. The history inscribed in the surface of our mud floor is a version of the history of the house we built with our own hands and of our lives in it since 1971. (p. 9)

The reader will notice some repetitions in this book: the essays’s disparate original publications are doubtless to blame for this. This isn’t to say that the essays are repetitious: each stands alone complete, and might best be read that way rather than being gulped done all at once. This book feels like a coda to Mayordomo; while Crawford makes this seem entirely normal, the situation that he describes is so outside the experience of most Americans’ civil interactions that it stands redescription. It would be nice to have more from Crawford; but one senses that he’s busy living.

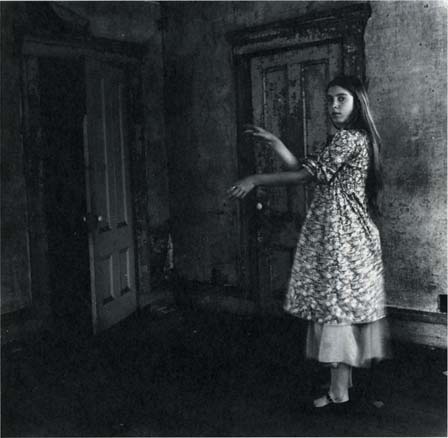

untitled, providence, rhode island 1975–1976

(Francesca Woodman, untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–1976.)

jane bowles, “two serious ladies”

Jane Bowles

Jane Bowles

Two Serious Ladies

(originally 1943; published in 1966 as part of My Sister’s Hand in Mine: The Collected Writings of Jane Bowles, Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

It’s a crying shame that Two Serious Ladies is only in print as part of Jane Bowles’s Collected Works: not that there’s anything wrong with the rest of her Collected Works, it’s simply that Two Serious Ladies is so perfectly complete on its own; it deserves to be a Penguin Classic, not one of the ugly redesigned ones, but one of the differently ugly older ones with the light green covers that didn’t smack of marketing, only belief in the power of literature. At one point, it could have been a New York Review Book, shelved between James Schuyler’s Alfred & Guinevere and James McCourt’s Mawrdew Czgowchwz. I don’t know what happened to Two Serious Ladies that it should be tied up so; maybe this is FSG’s fault.

Two Serious Ladies is a weirdly structured book. The first chapter, 34 pages long, introduces Christina Goering, a rich woman, strange from her religion-obsessed youth. Much later, she is visited by Lucy Gamelon, the cousin of her governess, who has heard stories about Christina; though Lucy worked in publishing, she is not up to anything, and she promptly moves in with Christina after her second visit. Some months later, Christina is invited to a party; she sees her acquaintance Frieda Copperfield, who is distraught about a trip she will have to take. She is then distracted by a morose man named Arnold, who she goes home with, thinking this is the interesting thing to do; she stays the night at Arnold’s house, where she meets his parents, who she likes better than Arnold. Christina sells her house and moves to a smaller house on an island. The second chapter, 75 pages long, is about Mrs. Copperfield’s trip to Panama with her husband; Mrs. Copperfield evidently hates to travel, but she leaves her husband for Pacifica, a prostitute. The third chapter, 90 pages long, returns to Christina Goering: she is now living in a house on an island with Arnold and Lucy Gamelon; eventually, they are joined by Arnold’s father. Christina has an affair with Andy, a man she meets in a bar; she leaves him after a week for a monstrous man named Ben who takes her for a prostitute. Five pages from the end of the book, Frieda Copperfield returns, evidently having returned to the city with Pacifica, who is running after a boy.

The plot is not why I find myself reading this book over and over again; rather, it’s the way in which the characters behave. In a characteristic passage, Christina Goering and Lucy Gamelon are sitting outside their house; Lucy is thinking about how much she hates Arnold. “He is even too lazy to court either of us,” she tells Christina, “which is a most unnatural thing you must admit – if you have any conception at all of the male physical make-up. Of course he is not a man. He is an elephant.” But Lucy most hates Arnold for freeloading on Christina, which is of course something that Lucy is also doing:

They sat in silence for a few minutes. Miss Gamelon was thinking seriously about all these things when suddenly a bottle broke against her head, inundating her with perfume and making quite a deep cut just above her forehead. She started to bleed profusely and sat for a moment with her hands over her eyes.

“I didn’t actually mean to draw blood,” said Arnold leaning out of the window. “I just meant to give her a start.”

Miss Goering, although she was beginning to regard Miss Gamelon more and more as the embodiment of evil, made a swift and compassionate gesture towards her friend. (p. 115)

Within ten pages of this scene, Arnold is calling Lucy “Bubbles” and they are sharing a room, united, perhaps, by their dislike for each other. None of the characters in Two Serious Ladies are likeable. They are not pleasant; at one point Arnold describes Lucy as “constantly in either a surly or melancholic mood,” which could be said about any of these characters. There is no pretense of redemption: these characters start out terrible and they will end terrible. This makes it a very funny book; but, in a way, it’s also more realistic.

There’s something interestingly off in the way the characters in this book make choices; they are all inscrutable. Here, an interaction between Christina Goering and Andy, her would-be paramour:

“Step back a little farther, please,” he said. “Look carefully at your man and then say whether or not you want him.”

Miss Goering did not see how she could possibly answer anything but yes. He was standing now with his head cocked to one side, looking very much as though he were trying to refrain from blinking his eyes, the way people do when they are having snapshots taken.

“Very well,” said Miss Goering, “I do want you to be my man.” She smiled at him sweetly, but she was not thinking very hard of what she was saying. (p. 166)

There’s a disconnect between thought and action that’s funny as well as terrifying: none of their behavior is at all predictable. In another novel, this sort of action could be accounted for by drugs, which would feel like a narrative copout; but these characters are entirely straitlaced, and even drinking doesn’t reliably change their inhibitions.

This isn’t quite surrealistic whimsy, though the characters do appear to move in dream-like trances: at least in the sections based around Miss Goering, the sense is less of a world gone strange than it is of strange characters who don’t fit into the regular world, characters who could not be described as surrealist dreamers. Miss Goering and her friends appear to move from Manhattan to a largely rural Staten Island, perhaps the Staten Island that Arshille Gorky painted to look like the south of France; the setting is identified by geography rather than by name, but it maintains the prosaic stolidity one expects from that borough. For excitement, they take a ferry to New Jersey, where things seem to be much the same. (There’s a certain similarity to Kafka’s Amerika, though that would have been published in English after Two Serious Ladies.) The Panama that Frieda Copperfield visits is more fantastical; I find myself less drawn to this part of the plot partially because we’re used to seeing Latin America described as a fantastical place where anything can happen. The drama there is still very much more personal than based on its setting: what happens to Mrs. Copperfield on her trip is not what would happen to anyone else, but Mrs. Copperfield and Pacifica don’t sparkle quite as brightly as Christina Goering and her followers.

It’s left to the reader to discern what exactly the narrative of Mrs. Copperfield and Pacifica has to do with the story of Christina Goering; presumably Copperfield & Goering are the eponymous two serious ladies of the title, although Lucy Gamelon appears more often in the book than Frieda Copperfield does. In their final discussion, Frieda gives an idea of what she might have been trying to do:

“But you have gone to pieces, or do I misjudge you dreadfully?”

“True enough,” said Mrs. Copperfield, bringing her fist down on the table and looking very mean. “I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I’ve wanted to do for years. I know I am as guilty as I can be, but I have my happiness, which I guard like a wolf, and I have authority now and a certain amount of daring, which, if you remember correctly, I never had before.” (p. 197)

Ms. Goering promptly admits her dislike for Mrs. Copperfield; there seems to be something incompatible about the way that the two of them are working out their lives. When we first meet Christina, she is purifying a young friend’s sins in a ceremony involving a burlap sack and a great deal of mud; through her narrative, talk of sin comes up from time to time. Christina and Lucy, for example, get into an argument about whether sports give Christina a feeling of sinning. Near the end of their affair, Christina realizes that Andy’s self-image has improved and he no longer thinks of himself as a bum:

This would have pleased her greatly had she been interested in reforming her friends, but unfortunately she was only interested in the course that she was following in order to attain her own salvation. (p. 172)

Christina’s theology seems to be her own brand of gnosticism: like Irenaeus’s description of the libertine gnostics, she seems to be trying to save herself through absorbing the sin of the world, which must be destroyed for truth to appear. Frieda, by contrast, appears to finally be enjoying the broken world as it is.

july 11–july 15

Books

Exhibits

- “Mind and Matter: Alternative Abstractions, 1940s to Now,” MoMA

- “Bruce Nauman: Days,” MoMA

- “Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917,” MoMA

- “Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography,” MoMA

- “Contemporary Art from the Collection,” MoMA