Monthly Archives: August 2010

the beach in august

The day the fat woman

In the bright blue bathing suit

Walked into the water and died,

I thought about the human

Condition. Pieces of old fruit

Came in and were left by the tide.

What I thought about the human

Condition was this: old fruit

Comes in and is left, and dries

In the sun. Another fat woman

In a dull green bathing suit

Dives into the water and dies.

The pulmotors glisten. It is noon.

We dry and die in the sun

While the seascape arranges old fruit,

Coming in with the tide, glistening

At noon. A woman, moderately stout,

In a nondescript bathing suit,

Swims to a pier. A tall woman

Steps toward the sea. One thinks about the human

Condition. The tide goes in and goes out.

(Weldon Kees, from Poems 1947–1954.)

august 11–august 15

Books

- Georges Perec, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, trans. Marc Lowenthal

- Wallace Shawn, Essays

- Julian Jason Haladyn, Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Films

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, dir. Howard Hawks

Exhibits

- “Charlotte Posenenske,” Artists Space

- “The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today,” MoMA

- “Item,” Mitchell-Innes & Nash

- “Ragnar Kjartansson,” Luhring Augustine

- “Le Tableau: Curated by Joe Fyfe,” Cheim & Read

julian jason haladyn, “marcel duchamp: étant donnés”

Julian Jason Haladyn

Julian Jason Haladyn

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

(Afterall Books, 2010)

I sporadically follow Afterall’s One Work series, probably not as well as I should; most look interesting, but only a few look immediately interesting enough to put down money for. They’re small books, and the concept is good: a close reading of a single piece of visual art presented for a general audience. This one follows on the heels of the big show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art last year focused on Étant donnés; it reminds me that the catalogue is still sitting on my shelf, waiting for a closer reading. This book is conveniently sized for subway reading; thus I’m getting to it more quickly.

What’s most immediately interesting to me about Haladyn’s reading of Étant donnés is that he bases it around a reading of Raymond Roussel. (For what it’s worth, I found my way to Duchamp through Roussel; encountered after Roussel, the way Duchamp works makes perfect sense.) Roussel’s influence on Duchamp has long been known; but there haven’t, to my knowledge, been many readings of exactly how that influence worked, perhaps because it was difficult for a long time to get a handle on Roussel’s work. Julio Cortázar, for example, was interested in the connection between the two. This is easier now for an English audience now that there are two biographies of Roussel in English as well as Exact Change’s compilation How I Wrote Certain of My Books; Foucault’s book on Roussel, odd as it is, is newly back in print as well. Haladyn refers to most of these in his text. Crucially, Haladyn connects Roussel’s posthumous publication of How I Wrote Certain of My Books to the posthumous unveiling of Étant donnés. I don’t know whether a direct connection can be made – during his life, Duchamp indicated that seeing Roussel’s theatrical works was pivotal for his early works, but it’s unclear whether Duchamp knew about what Roussel was up to after his death. Duchamp would certainly have known people who would have known about Roussel – Michel Leiris, for one, as well as the members of the Oulipo – but my sense is that the historical record is somewhat dark on the subject. Foucault’s book, for example, came out in 1963, when Duchamp was almost finished with his work; and Duchamp doesn’t seem to have said anything in print about Roussel and seemed surprised by Michel Carrouges’s earlier argument about his influences. But as he admits in that letter, there are clear affinities. Haladyn declares that there was an “extreme unlikelihood” that Duchamp saw Courbet’s L’Origine du monde before constructing his nude (a statement undercut by his footnote, where he admits the possibility that Duchamp could have seen a reproduction); but not considering the possibility that Duchamp didn’t actually know about Roussel’s procédé undermines an otherwise extremely interesting argument about the similarity of Roussel’s procedure and Duchamp’s inframince. The lack of discussion of Duchamp’s own use of homophones is also an odd omission.

Haladyn structures his book around finally visiting the Philadelphia Museum to see the work in the flesh – Haladyn is Canadian, based in Ontario – his narration of his approach to the work is odd in part because he doesn’t mention that he’s visiting the exhibit not in its normal state, when it quietly waits behind its non-descript vestibule, but in the midst of an exhibition based around the work, in which there are lines of people waiting to look through the peep holes. This isn’t how the work is normally seen; if one observes casual visitors in the Duchamp room at the PMA, most are unprepared and don’t discover Étant donnés at all. Once in a while, someone does by accident: there’s a burst of excitement, everyone goes to see what the matter is, and sometimes people are shocked. (There’s no warning label on the room yet; one wonders how often mortified parents complain to the staff.) But it’s strange that Haladyn should describe the act of waiting to look as a normal part of viewing the work: it seems integral to the experience that it should take place in a room that seems like it might have been left open by accident.

The titles of Duchamp’s best-known works (Nude Descending a Staircase, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even) promise prurience that the objects themselves comically fail to deliver; Étant donnés does the opposite and is consequently even more shocking. Haladyn stresses that this work is very much about the role of the viewer, following Duchamp’s argument in “The Creative Act”: it is the viewer’s experience of the piece, with the shock entailed in it, that gives it meaning:

If, therefore, it is in and through the eyes of the viewer that the creative act reaches its climax, it seems appropriate that Given addresses the eye in such an overdetermined manner. Too look into this installation is to be (made) aware of the fact that one is looking. . . . Significantly, the immanent moment of being caught peeping through the door of Given by another viewer’s gaze is intimately part of the process of viewing this installation whether or not the moment actually occurs. (p. 82)

Released posthumously, there is no way to ask Duchamp what his work meant. Roussel’s How I Wrote Certain of My Books offers a posthumous explanation of his work, as well as providing an instruction manual to those who would create work like it; Duchamp also release an instruction manual after his death that also allows one to recreate it. This is an extremely tempting correspondence; but there are also extreme divergences between the two creator’s posthumous performance. Roussel was baffled when his public wasn’t astonished by his genius during his life; he assumed that his explanation would make it clear to the public, in didactic fashion, how they’d be wrong. Duchamp offers no such guidance; as he’d explained earlier, there was no solution because there was no problem. Haladyn’s book, though promising, isn’t entirely convincing; but it’s an interesting start, and he could profitably expand his argument.

wallace shawn, “essays”

Wallace Shawn

Wallace Shawn

Essays

(Haymarket Books, 2009)

This book has been hanging around the bedroom forever; I don’t remember whether how it turned up in the house. I found myself interested in it when listening to an interview with Wallace Shawn in which he talked, rather perceptively, about Harvard class books. Class books are sent to those graduates for whom the alumni office has the address every five years; they’re very strange documents, as class members are allowed to write a statement describing themselves, presumably for members of their class that haven’t seen them for a while and might be wondering what they might be up to. (See, for example, filmmaker Irene Lusztig’s Class Notes project, where she recruits volunteers to read some of the entries from her ten-year book aloud on video.) These are very strange statements: there’s an awful lot of self-justification and soul-baring, and some brave soul could probably connect them to the Puritan tradition if Sacvan Bercovitch hasn’t already done that. Wallace Shawn, coming from privilege, is interested in the way privilege functions in America and is willing to talk about it; most people from his position avoid the subject entirely as being gauche. Shawn rightly finds the subject interesting: the majority of the members in his class seem to think that “life is good,” though the outside world is going down the tubes: a weird contrast, and one that might bear more scrutiny, in the style of Henry Adams. As someone who found myself in that realm largely by accident, as a cultural foreigner, I was interested in this book.

As it turns out, Shawn doesn’t discuss Harvard class books in the essays here, though there is a similar focus in a few of the essays. This isn’t an especially consistent collection: there are a number of short pieces written for The Nation and similar places which, while funny, feel rather slight when read in the context of a book. Coherence is also lost because these pieces cover a long span of time, from 1985 to last year; most are from the last decade, and the earlier pieces fit don’t stand out too far. About half are political; a quarter are concerned with the theater; and the rest of the space is taken up with two interviews, one with Noam Chomsky and the other with Mark Strand. But the overall effect of this hodgepodge is to create a single viewpoint’s perspective on a dark decade, a decade in which the left was dissatisfied and ineffective. Perhaps over time this will seem more interesting, as this will be a decade that historians will scrutinize; right now, looking back feels vaguely dispiriting in the same way being there did. But it’s a little book; most of the pieces don’t overstay their welcome and it’s a quick read.

It’s an interesting book because Shawn’s position is the same as most of the people I know: over-educated, interested in the arts, and deeply dissatisfied with the state of the country, and his attempt to make sense of the world is coming from a similar place to theirs. When seen in print, though, it’s strange how unfamiliar this perspective seems: maybe this is my fault, as I know that I increasingly found myself skimming things like The Nation or Harper’s because things were so bad issue after issue: what The Onion called “outrage fatigue.” But it also seems entirely possible that there haven’t been enough people complaining about what became normal in the past decade: the militarism, the flag-waving, the bizarre way in which “¿quién es más macho?” seemed to have become the deciding factor of American politics and elections. Shawn rightly wonders about this: he feels out of touch and hopeless in this world, a position that I think many of us find ourselves in. It’s important that this dissatisfaction isn’t coming from an explicit ideology: rather, as read here, Shawn presents himself as someone trying to live in a world gone mad. I don’t know how well some of these pieces would have come off in their original presentation in The Nation: at this point in time, one reads The Nation because you’re part of the American left, not because you’re part of the general reading public.

I wish that I would care more about the theater than I do: in theory, of course, it’s fantastic, but paying proper attention to it (like many other possible pursuits) requires more time and effort than I’m willing to give it based on the expectation on what I’d get out of it given my occasional casual experiences with it. That said, I like reading Shawn’s attempts to justify writing for the stage here, in no small part because it’s an attempt to justify art production of any sort in a world that doesn’t recognize that as productive work. I don’t think, of course, that there’s any need for him to justify what he does to the world; but most in his position wouldn’t bother or would take their worth for granted. Shawn notes that there isn’t a diverse playgoing culture in New York (to say nothing of the rest of the country); it’s hard to make an argument for theater as a popular art when it’s predominantly restricted to the upper class. This isn’t a new argument, of course, though one that can increasingly be applied to a wide range of artistic forms – the literary novel, for example; but it’s interesting to see this taken into account by someone who’s involved in this sort of production.

The best essays in this book (“The Quest for Superiority,” “‘Morality'”) are those that try to break us out of our cultural assumptions, as Americans and as, presumably, cultural elites. The upper classes have odd ideas, which aren’t often interrogated; and it’s to Shawn’s credit that, as the consummate insider, he can notice how strange the familiar can sometimes be. Privilege often goes unquestioned in American life. I don’t know that this is exactly the book that I would have liked it to be; but there is still something interesting here, as incoherent as it might be.

the coffin house

(Denton Welch, The Coffin House, watercolor and ink on paper, 1946, private collection. Recently on show at Tibor de Nagy’s “Town and Country”.)

georges perec, “an attempt at exhausting a place in paris”

Georges Perec

Georges Perec

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris

(trans. Marc Lowenthal)

(Wakefield Press, 2010)

This is the third book from Wakefield Press: it presents a full translation of Georges Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris. This is a minor work in the Perec landscape, which receives only a glancing mention in David Bellos’s enormous biography. It’s encouraging that there have been a steady flow of new Perec books, no matter how small: 2008 saw Atlas publish Cantatrix Sopranica L.: Scientific Papers, and last year saw David Godine publish Thoughts of Sorts, both previously excerpted in Penguin Species of Spaces (as well as the revised translation of Life a Users Manual, of course). It’s nice seeing Perec’s books as small self-contained objects; the Penguin volume, which presents a lot of material, is too easy to skip through. At 55 pages, this book is shorter than the other two, short enough for me to read on the brief flight from Norfolk, Virginia to Baltimore, though it’s a book that demands re-reading.

As the length suggests, this is a self-consciously minor work: it might be considered an investigation in boredom. Perec chose a place in Paris – Place Saint-Sulpice (visible, not particularly well, on Google Earth and visited it nine times from the 18th to the 20th of October, 1974, four times the first day, less on the following ones, attempting to write down everything he saw. The results are this book. There is pointedly nothing particularly remarkable about the location, and in his introduction Perec makes clear his intention not to write about Saint-Sulpice’s notable features: rather, Perec was attempting to find something interesting in the ordinary, a project that he’d soon expand (restricting the span of time, but increasing the space to an entire building) into Life a User’s Manual.

This is a personal exercise, and because it follows his attempts over time, it feels very much like a series of notes: the reader observes the observer, and how he begins to notice things. He starts his first session by writing down all the text that he can see, then moving on to different sorts of categories (“fleeting slogans,” “ground,” “trajectories,” “colors”). Things start quickly: he’s trying to get everything down. Then there’s a slowing: he tries to notice what changes over time. For a while he’s preoccupied with the many buses that pass through the square (the second section is largely a record of the buses that pass as he watches); then he gets bored of noting the buses; and finally in in the fourth section he realizes that he can describe a bus not simply by the number of its route or where it’s going but by how full it is. It’s a tiny moment of revelation: of looking at something ordinary long enough to see something new in it.

A few personal details pop up: he tells what he’s eating or drinking, and a couple of times he sees people pass that he recognizes. One wonders how personal some of the details might be: why, for example, does he mention an”apple-green 2CV” over and over? Is it the same car? Was there a reason that his attention might be drawn to this make and color of car over others? Or were there simply a lot of them in Place Saint-Sulpice in 1974? The writer is sometimes bored with his project; one wonders why he stopped on the third day. By writing on a Friday, a Saturday, and a Sunday, he’s presumably covered most of the weekly variation likely to occur; but looking longer might have brought more out. Perhaps it’s left as an exercise for the reader.

Perec’s project is a generative one, of course. Reading it, I found myself thinking most often of Daniel Spoerri’s work, first his “snare paintings,” where he’d glue down the detritus of a meal to the table and exhibit it on the wall; later, he created a literary equivalent of this in his Anecdoted Topography of Chance, mentioned in Marc Lowenthal’s very nice translator’s note. In both, Spoerri was attempting to create meaning from trash; the Topography uses trash on a table to generate narrative, albeit a narrative more personal than Perec’s. Spoerri and his friends could generate a narrative from their personal trash because there was something personal that could be seized upon there: how the trash got on the table, where the trash was from. Lowenthal also mentions Joe Brainard’s I Remember, another generative trick that Perec brought into French; this also relies on the personal. What Perec is doing in An Attempt might be something trickier: he’s trying to make an utterly anonymous public space personal. It’s a difficult job: ultimately, this is more of a record of Perec’s time there over three days rather than a depiction of a place. Perec isn’t depicting the square, he’s exhausting it (as well as himself); by the end, he clearly wants to go home. This is a lonely book.

I’m still kicking myself for missing MoMA’s program of Perec’s film work a few years back; I suspect that familiarity with his work in film, generally inaccessible in this country, might illuminate this book a bit more. One can’t have everything, I guess; it’s nice that we have as much of Perec’s writing in English (and in print) as we do now. Again, it makes me happy that Wakefield is publishing books like this: most publishers wouldn’t bother with a slip of a book like this, no matter how well it works. This book is as attractive as the two previous books from Wakefield, the first of their “Imagining Science” series; I’m curious to see where they’ll go with that. The paper is thick: it’s a pleasure to read. As mentioned, the translator’s note at the end of the book by Marc Lowenthal helpfully explains the text without lapsing into the overly academic; this kind of attention to detail is important, and it makes Wakefield’s work worth following. I’m particularly interested to see how their volume of Fourier turns out: but that’s next year.

august 2–august 10

Books

- Ettie Stettheimer, Love Days [Susanna Moore’s]

- Alvin Levin, Love Is Like Park Avenue

- John Crowley, Lord Byron’s Novel: The Evening Land

- Joseph McElroy, Preparations for Search

Films

- Man on Wire, directed by James Marsh

- Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog

- The Hours, dir. Stephen Daldry

joseph mcelroy, “preparations for search”

Joseph McElroy

Joseph McElroy

Preparations for Search

(Small Anchor Press, 2010)

This is a short book, a chapbook really, of material that was cut from Joseph McElroy’s biggest work, Women and Men. An earlier version of this was published in the journal Formations in 1984; I can’t tell why this is coming out now. A volume of McElroy’s stories is coming out in the fall from Dalkey Archive; I don’t know if that includes this, though I suspect it doesn’t. For the past few years, he’s been reading from a short novel called Cannonball which still doesn’t seem to have found a publisher, and he seems to still be working on his non-fiction book on water, which I’ve been awaiting impatiently. But any new McElroy material, no matter how unexpected, is a source of excitement to me: this is a small book, but one that lends itself to re-reading.

The plot is easily related: a character named Enos comes to the narrator, Bethel, asking to borrow $1100 so that he can hire a detective to find his father, who left when he was two. The narrator is reticent to do this; other characters (who seem to be in their late twenties and early thirties in downtown New York in the early 1980s) are consulted, and a world is quickly fleshed out around this initial situation; it’s similar to when a pebble dropped into still water, and ripples move across an entire pond, hit the edges, and are reflected to create complex and unpredictable patterns. Here the patterns are created in the people in Enos and Bet’s worlds: their girlfriends, their relations, their friends. A world is slightly destabilized; it struggles to come back to stability. The interest in the book is in seeing how the characters react to a change – a slight one, but still a change – in their environment: it could be said that this is an ecological approach to fiction.

There’s something distinctive about the voice McElroy uses: I’ve always suspected that Don DeLillo learned a few tricks from him, though DeLillio amplifies the voice until it becomes cartoonish. It’s an internal narration, but it’s an oral narration: you can hear the narrator saying what he relates, the rhythms are those of speech rather than that of the page. In this section Bet puzzles out a relationship; Matt is Enos’s father; Elizabeth wrote Enos’s mother a letter long ago:

Elizabeth had worked with Matt in the office of a lumberyard in Salem, and she loved him though she didn’t think he was the marrying kind, as she put it. But why were Susan and I piecing together this old story as if it were not so full of gaps as hardly to be a story? What did Elizabeth look like, I guess you always want to know. The letter had been typed and was the only news Enos’s mother had ever had. Confusing, for at the time Elizabeth wrote it, Matt had just the week before quit the lumberyard in Oregon and gone down to California, to San José, where he had a job working construction. There was more to it than that. Susan recalled that this woman Elizabeth had been already once a grace widow.

As for me, I remembered what Susan didn’t know – that the lumber firm in Salem sold out soon afterward. But Susan now recalled that Matt’s girlfriend Elizabeth had been planning to leave Salem anyway. I now recalled that the former manager of the lumberyard there was named Deed, and he had been the one who according to Elizabeth’s letter had told her that Matt was in trouble as a labor agitator down in California. (p. 24)

The words are very simple; but the syntax is complicated, looping back and forth to cover a range of times. As the concern for “this old story” suggests, it’s a carefully literary voice: what’s being recounted here is something that’s past what a single oral narration could explain, a complexity that only literary writing can deal with properly. The section breaks create a rhythm only possible on the page, and the system of quotation – no quotes for recounted dialogue, quotation marks for dialogue that is happening in real time – suggests that thought has gone into creating something that works as a text. An auditor is occasionally possible; it’s hard to tell if this auditor is another character or the reader trying to understand the text.

It’s a dry voice: there are echoes of the disinterested way in which Kafka relates “In the Penal Colony,” for example, though the use to which that voice is being put is very different: McElroy is deeply interested in the social world that seemed to terrify Kafka: rather than depicting a mechanistic world, the result of positivism, he depicts a world that’s deeply complex because of the myriad interactions.

Preparations for Search seems to almost be a miniature version of The Letter Left to Me (the short novel that McElroy wrote after Women and Men: to my mind it works a bit better than that book because of its extreme compression, but Letter explores this book’s concerns about the meaning of paternity more deeply. McElroy works by digression: digression for him is a tool to achieve verisimilitude in a complex world. I think his reputation has suffered slightly because of the shallowing of the pool of readers between the 1980s and the present: his work is unremittingly serious, an attempt to use fiction to think about the problems faced by the modern world, and I think that today’s readership, driven to distraction by endless amounts of entertainment, has a harder time sitting down with his large books. This is a shame: his work hasn’t lost anything over time but its audience; maybe his output of shorter works this year will regain some of that.

It’s hard to tell very much about Small Anchor Press, the publisher, from their website; they seem to be new and based in Brooklyn, and it’s unclear to me how they came to be publishing McElroy. Preparations for Search is an attractive volume: the front cover looks good, though I don’t entirely understand the rationale for the square form, as it’s difficult to make a text block look good on a square page; consequently, the measure is a bit too wide for my taste. The presentation is a bit oblique as well: the text is composed of different sections, some only a paragraph long, and section breaks have become page breaks, giving the book an almost aphoristic look. This becomes confusing with longer sections that span pages (a problem also found when setting poetry); it can be hard to know whether a paragraph break at the end of the page is a section break as well, which matters when the sections present discontinuous moments in the book’s narration. But these are quibbles: it’s nice to see any new McElroy work, and any press that’s publishing him is worth keeping an eye on.

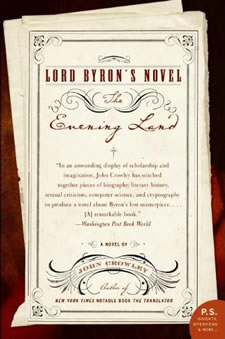

john crowley, “lord byron’s novel: the evening land”

John Crowley

John Crowley

Lord Byron’s Novel: The Evening Land

(Harper Perennial, 2005)

One of the virtues of John Crowley’s book is that they can often be found in awful bookstores when it doesn’t seem like anything readable can be dredged up. I started reading the Ægypt books in Idaho; here in rural Virginia, I found myself a paperback edition of Lord Byron’s Novel: The Evening Land, which I wisely hadn’t gotten around to reading yet. It’s pleasant to read his books when cut off from civilization, although they’re the sort that do cry out for the Internet for fact-checking. Did Dr. Merryweather’s Tempest Prognosticator really predict the weather by means of leaches? Wikipedia claims this is true; their entry on Ada Lovelace, though, reads like the Book of Genesis, multiple authors telling the same stories over and over again in the hopes of eventually getting it right. One wishes for a better version of Byron’s poetry than the easily accessible Project Gutenberg editions; you can’t have everything. The dictionary app on my iPhone has a definition for “operose”: that’s something.

Lord Byron’s Novel consists of three parallel narratives. The first is Lord Byron’s novel, given the title The Evening Land, ostensibly saved from destruction at the hands of his wife by his daughter, Ada Lovelace, whose notes to the novel, at the end of each chapter, create a second chronology, following her reading of the book. Byron’s text takes up the majority of the book. Interlarded between chapters is a discovery narrative, composed of a trail of correspondence, mostly emails, sent to and from Alexandra Novak, an American woman in London doing research on Ada Lovelace for a website devoted to the forgotten history of women in the sciences; Ada has encoded the novel, and Novak and her partner seek to decode it. There’s not a great deal of suspense in this, as the reader has been reading Byron’s novel and knows that it’s accomplished. Rather, this third narrative seems to be working at different ends, examining what coincidence means in fiction and in life. Another plot emerges: Alexandra’s father, conveniently enough a former Byron scholar, has been estranged from his daughter: having left academia for a career in the movies, he commits a Polanski-like crime for which he must flee the country; largely on account of this, he is estranged from his daughter. Relations between fathers and children form a dominant theme: between Byron and his daughter Ada, who he never talked to; between Alexandra and her father; and between Byron’s hero Ali and his fictional daughter Una.

It’s neat, but not too neat. It’s difficult when reading a novel which consists of interplay between a text and its annotations, to avoid thinking of Pale Fire, which has almost always done the job more perfectly. Not that perfectly is necessarily the same thing as better: Nabokov’s book is constructed so tightly that it could only be fictional, and in its unrealistic world there’s no friction where the reader might be caught and held. Crowley doesn’t seem to be attempting to compete with this: his project here is different because there’s an interplay between the real biographical history of Byron and those around him and the fictionalizations that Crowley has created. When the reader is presented with a text ostensibly by Lord Byron with annotations by his daughter, Ada Lovelace, it’s clear that the exegesis in the notes actually operates in reverse. The similarities that Ada finds in Byron’s text to his own life aren’t the signs of a novelist disguising his own life by hiding it in fiction, but rather the raw materials that the reader knows that Crowley has used to construct a novel that might be Byron’s. The reader suspects that the notes might have preceded the novel: they’re the historical pieces from which fiction might be constructed.

This works in other ways as well: when a character appears named “Lord Corydon,” we know that we understand the name “Corydon” differently from the way that Ada would have, as Gide’s work wouldn’t appear until well after her death. Ada’s notes point out that Byron’s account in his novel of how the Duke of Wellington won the Battle of Salamanca is counterfactual; but we also know that the very existence of Byron’s novel (and Ada’s notes on it) is counterfactual. The author is winking at us: in less deft hands, this might be annoying, but it doesn’t happen often enough here to wear out its welcome. The text that is to be decoded appears mysteriously, in the hands of a figure who might be the author himself; late in the process, he appears again, to cast doubt on the truth of the rediscovered novel.

This isn’t experimental fiction, in the sense that Pale Fire was experimental when it appeared; rather, it takes a form (albeit one that hasn’t been used especially often) and puts it to good use. It’s a pleasant book, exactly right for vacation reading: hence my pleasure at being able to find John Crowley’s books in remote bookstores. The Evening Land might have stood alone: it’s an enjoyable pastiche of Romantic writing, a bit reminiscent of James Hogg’s Private Confessions of a Justified Sinner though without the supernatural aspects of that book. Someone must be compiling a dissertation on the appearance of the Internet in American fiction: Crowley’s grasp of the way people talk over email is surprisingly convincing and readable, and would belong in such a volume. In the earlier sections of the book, one finds oneself racing through the pseudo-Byron to reach the contemporary narrative; as the book progresses, interest reverses itself; it’s skilled writing that can maintain such interest.