Stanley Crawford

Stanley Crawford

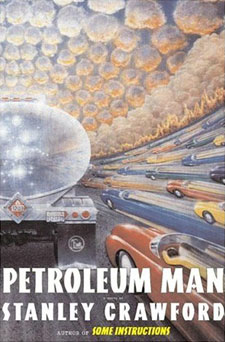

Petroleum Man

(Overlook, 2005)

It’s a truism that most great artists aren’t nice people, in exactly the same way that most great businessmen aren’t nice people, or in the same way that anyone who’s devoted to one thing above all will prove lacking in the rest of life. One starts thinking about this very quickly when considering the work of Stanley Crawford: because he does seem to be that rare example of the artist who seems to understand the problem of living decently. One reaches this conclusion from his non-fiction work, which focuses on agriculture; but one can also arrive there through his fiction. Almost all of it (Gascoyne, Log of the S. S. The Mrs. Unguentine, Some Instructions, this book) focuses sharply on dictatorial male characters who are set on ruining the world, domestically or more broadly construed, in some way. Travel Notes, his second novel, seems to diverge most widely from this plan, but the narrator of that book might be roped into this schema without too much trouble. Though satirical, Crawford’s monomaniacs might be seen as a critical inquiry: what makes people behave this way? And what can be done about them? Crawford’s own response is a life of rural agrarianism in New Mexico, but his continued treatment of these characters in his fiction suggests that he hasn’t finished trying to understand them as a problem.

Petroleum Man, as its title suggests, is his most explicitly political novel. Published in 2005, it can’t help but be read as a novel of the Bush administration. Leon Tuggs, the protagonists, deprecatingly refers to his adversaries with the specific epithet (a Reaganism?) “liberal democrats” (the italics are his); their opposite numbers are “Conservative Republications“. Tuggs is a close personal friend of the President; by his own account, he is the most wealthy businessman in America (and perhaps the world), having achieved this position by selling something named “the Thingie®” which is made out of wood, and the precise function of which is left unclear (a nod, perhaps, to what is made in Woollett in Henry James’s The Ambassadors); it is, he says, an “unchallenged tool used to keep track of the proliferating things of the world.” His “liberal democrat” son-in-law informs him that there is “a glob of Thingies® all stuck together the size of a small iceberg floating off the coast of Southern California and that Thingies® have cause the death of millions of ocean-going fish by getting stuck in their gills and seabirds by getting caught in their throats” (p. 86) – but Tuggs, every inch the industrial villain, has little time for such concerns. Tuggs writes the book while in the air in his private jets; with an eye to his legacy, he has embarked on a program to give his two grandchildren, Fabian and Rowena, a series of scale models of every car (with a few planes, for good measure) that he’s owned; each model comes with explanatory text telling, at least in part, his life story as well as detailing his ongoing struggles with the rest of his family and the broader world.

Despite having a family, Tuggs is much better with things than with people; his fortune, he explains, stems from his General Theory of Industrial Sex, which mostly goes unexplained, but seems to stem from his observation that since sex can be found everywhere in the metaphors of the industrial world (nuts and bolts, plugs and sockets, etc.) there is no need to look for it in the considerably messier world of people. The position of Tuggs is that of Ayn Rand: he sees a rational world in front of him (found though the lens of engineering), and is purposefully blind to everything outside of that world – his family in the throes of collapse around him. His grandchildren, to whom his narrative is ostensibly dedicated, don’t seem to be interested in the slightest in his educational program, being, as they are, scions of a wealthy family above all else. But telling his life story through cars owned is the only way Tuggs can express himself: his world is the world of things. He yearns for the day when human advance will finally overtake the natural world:

This should be not far off, according to the figures I am being supplied concerning the paving over of raw land and the converting of forests into useful industrial products like Thingies® and the plans for processing useless icebergs into drinking water and – of course – into bags of ice to help counter the effects of global warming, which I have always regarded as yet another business opportunity, perhaps the greatest ever in the history of civilization. At the present moment, the main tool is the computer – which appears to work flawlessly, however, only in the movies. (p. 130)

The discordant introduction of the computer here points out how oddly anachronistic Tuggs seems as a figure of the American businessman: while everything, of course, can be made from petroleum, his fixation on the thing (as opposed to the human) seems out of place in an American economy that’s increasingly virtualized. His hated son-in-law, a lawyer for an investment, might point the way forward: like most financiers, Chip (note the name, of course) produces nothing but the abstraction of more wealth. (Fabian and Rowena, the reader assumes, probably will never bother to actually have jobs; they trade away their collection of laboriously constructed metal models of their grandfather’s cars for cheap plastic copies and cash to make up for their lack of an allowance.) There’s something almost laudable in Tuggs’s function as a producer: he is monstrous, but in his ridiculousness he is a comprehensible figure: we can see how he arrived where he is. His position at the end of the book is predictable: though he is more wealthy than ever, his family refuses to speak to him, and his long-suffering wife is suing him for “being the source of a drift onto her organic fields of illegal pesticides or herbicides or other substances not approved for organic production” when thousands of miniature hamburgers dropped from helicopters fail to hit his birthday party, as intended.

It’s always surprising how few American novels are about the mechanisms of capitalism and its effect on the businessman: off the top of my head, there’s The Rise of Silas Lapham, Melville’s “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” Nathanael West’s A Cool Million, Gaddis’s J R, Richard Powers’s Gain. It’s a big subject: there should be more.