B. Traven

B. Traven

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010; originally 1935.)

I have not, I should first point out, seen the John Huston film of this, which seems marginally better known than the novel; sooner or later I’ll get around to it, but I haven’t yet. This is a caper narrative, of course: something that’s set up early on and repeatedly emphasized is the corrupting power of gold, and the narrative tension is the question of whether any of the characters will be able to escape this. The characters are not very likable (with the possible exception of the experienced old man, who we suspect will pull through); but it’s impossible to tell three-quarters of the way through the book who the villain will turn out to be. The book is oddly structured: characters are introduced who seem like they might be significant, then they fade away. It’s true to life, but confusing for fiction.

The narration of this book is also confusing: there are frequent excursions for long stories (in the style of the Manuscript Found in Saragossa); though they are told by a particular character, they are in the same narrative voice as the rest of the book, an omniscient third-person. The narratives always seem to know things that they shouldn’t know (the thoughts of dead characters); in this sense, this might be thought of as a clumsy book. A paragraph in which a main character is killed, for example, starts with his thoughts, moves to a description of what he does, moves to the thoughts of his murderer, and describes the act of murder; the paragraph consists of nine sentences but the perspective repeatedly shifts. This doesn’t seem to be self-conscious in the style of Faulkner; rather, it’s the easiest way to tell the story. While written in 1935, characters think of what they’ve seen in the movies as a model for what might happen to them.

The social perspective of this novel might be unexpected. The first chapter concentrates on what work – or the lack of it – can do to a man, pointing out exactly how much money it costs to continue to exist when you have none. As noted, Traven’s character’s aren’t particularly sympathetic; he’s operating in the naturalist tradition of Dreiser or (more likely) Zola, and he’s deeply interested in how the machinery of the economy works. (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was contemporaneous with John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. Trilogy; they’re told differently, but the perspective of the danger of capital is similar.) One notices this now: contemporary novels concerned with work and how terrible it can be are very much the exception. The socialist novel has more or less disappeared; but here economic justice is openly debated by the characters:

“. . . The old man hasn’t stolen the goods. They’re his honestly earned property. That we know only too well. He didn’t get that money by a lousy cowardly stick-up, or from the races, or by blackmailing, or by the help of loaded bones. He’s worked like a slave, the old man has. And for him, old as he is, it was a harder task than for us, believe me. I may not respect many things in life, but I do respect most sincerely the money somebody has worked and slaved for honestly. And that’s on the level.”

“Hell, can your Bolshevik ideas. A soap-box always makes me sick. And to have to hear it even out here in the wilderness is the god-damned limit.”

“No Bolshevik ideas at all, and you know that. Perhaps it’s the aim of the Bolsheviks to see that a worker gets the full value of what he produces, and that no one tries to cheat a worker out of what is honestly coming to him. Anyway, put that out of the discussion. It’s none of my business. And, Bolshevik or no Bolshevik, get this straight, partner: I’m on the level, and as long as I’m around you don’t even touch the inside of the old man’s packs. That’s that, and it’s final.” (pp. 236–7.)

This is the point, of course, where it becomes clear who the villain is; there’s not so much a hero as another victim. The gold will be lost, as we’ve been told over and over again by the stories the wiser characters tell; the best one can do is to get by without ripping anyone off too much. The old man mentioned here comes out fine because he’s taken for a doctor by the natives; the natives are foolish, but, it’s made clear, better than the American interlopers or the Church which is cheating them. Men are in competition in this book; only a single notable woman appears in this book, Doña Catalina María de Rodríguez, described in a story in chapter 16: but she falls as well because she takes on the avarice that killed her husband.

One finds one pausing at the distinctive dialogue, which doesn’t sound quite like anything else. A representative passage of Americans speaking from near the beginning of the book:

“Aw, gosh,” said one of the sailors, “don’t talk so much squabash. It makes me sick hearing you. Come up, you two beachers, and we’ll stuff your bellies until they bust. We throw it away anyhow. Who the funking devil can eat a bite in this blistering heat? Gee, I wish I was back in that ol’ Los An, damn it.”

When they left the tanker, they couldn’t walk very far. They lay down under the first tree they reached.

“That was what I call a square meal, geecries,” Dobbs said. “I wouldn’t walk a mile even for an elephant tooth. I’m out for the next two hours. And we better get a rest.”

“Okay by me, sweety.” (p. 21)

Or later in the book, some Mexican bandits (previously established as only speaking Spanish) castigate each other after a murder:

“Aw, shut up, you damned yellow dog! Why didn’t you do it? Afraid of that funking son of a bitch by a stinking gringo, hey? I know who did it and bumped him. And I tell ye, get away from me, both of you chingando cabrones and que chinguen los cabrones a las matriculas. Do I need your stinking advice, you puppies? Out of my way, you make me sick looking at you, you dirty rats.” (p. 269)

anish. Generally when Spanish is used in the text, it’s followed by a restatement in English (“Tiene un cigarro, hombre? Have you got a cigarette?”); maybe profanities left untranslated are more powerful. The euphemisms “funking” and “geecries” appears all over the book rather than their antecedents; neither appear in the OED, and “geecries” would appear only ever to have been used in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, though it’s vaguely possible that Traven is using “funking” in the sense of “cowardly”. One wonders if anyone actually ever talked like this.

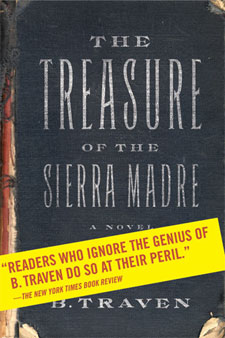

This particular edition is, it should be said, an embarrassingly ugly book. The insides have been reshot from some older, smaller edition, leaving the text box weirdly positioned on the page; the cover of this paperback employs the hoary old trick of trying to make it look like it’s a frayed old hardcover, the spine about to fall off, then negates that entirely by slapping a strictly two-dimensional yellow banner obliquely across the front declaring that “READERS WHO IGNORE THE GENIUS OF B. TRAVEN DO SO AT THEIR PERIL,” a quote sourced to the NYTimes Book Review, though one that I can’t find in their archive. Another tacky yellow banner adorns the back, with a blurb from John Chamberlain’s original review in the Times in 1935; the rest of the back cover ignores the concept of the front.) The back cover copies suggests that the book is worth reading because it may have inspired 2666, which suggests a certain amount of desperation. When confronted with a cover like this, one remembers Jan Tschichold’s dictum that dust-jackets of books should always be thrown away as advertising.

One wonders as well why there’s no editorial apparatus around this book, save a brief biography of Traven on the first page that uses phrases like “many scholars think.” Certainly an introduction could be cobbled together for a novel’s seventy-fifth anniversary edition. An interview with Vice last year (the source, probably, of the “many critics” connecting this book to 2666) could have been turned into something serviceable; a sharp editor might have had Blixa Bargeld put together something. A history of the text – if it started out in German, how much of it was the creation of the original editor – would be useful and probably of general interest, especially when the author’s life is being used to sell the book on its back cover.