Zachary Mason

Zachary Mason

The Lost Books of the Odyssey: A Novel

(Picador, 2010; originally Starcherone)

I wish I liked this book better than I did; it’s possible that I didn’t give it a very fair reading, as most of my first reading took place on a plane full of screaming babies which I attempted to drown out with Basic Channel. Some smart people whose opinions i trust (Michael Silverblatt, Tim Farrington) like this book and Mason comes off as sharp in interviews; but even re-reading it’s hard for me to be convinced that this book successfully manages to get past Homeric pastiche. Rewriting Homer isn’t such a new thing: there’s Joyce, of course, and Christopher Logue’s translations and Kleist’s extrapolations (in Penthesilea) if you want to go to the Iliad, and things like the second and third sections of John Barth’s Chimera aren’t tremendously far away from where this book ends up; nor, in another way, is Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Just looking at versions of The Odyssey besides Joyce’s, there’s Lucian and Kazantzakis; there’s Godard’s Le Mépris; there’s O Brother Where Art Thou; Samuel Butler’s re-imagined backstory and author; and this list could go on and on. When there’s company like that, it’s hard to get overly excited about the concept of this book: there’s a lot to measure up to that’s already out there, much that isn’t especially obscure and plenty that’s familiar.

First form. In what sense is this a novel? Is the subtitle Mason’s, or is it the publisher’s, hoping the book won’t be confused with The Lost Books of the Bible or the classics section, if it exists? There’s a whiff of the paradoxical (or oxymoronic) to books being glossed as a novel. The original Odyssey isn’t a novel, of course, it’s an epic in verse; it’s composed of books, but those books function differently than the books here. If one isn’t looking for a novel in it, The Lost Books of the Odyssey, unapologetically prose, appears to be a collection of short stories, many of them mutually exclusive. While the stories are connected thematically, there isn’t the sense of development (or even the consistent sense of chronology) that one expects of a novel; if it a novel, it’s in the maddeningly all-encompassing sense that Steven Moore uses the word in. The stories that make up this book can seemingly be read in any order with no loss. In this, it might be compared to the shuffleable innards of B. S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates or Milorad Pavić’s Dictionary of the Khazars; the aforementioned Calvino or Queneau’s Exercises in Style might be seen as forebears of this type of book. Pavić’s novel seems to be designed to point out how mutually exclusive different accounts of history are: the strategy works there because he’s ostensibly telling stories from Christian, Jewish, and Muslim perspectives; religious conflict is something that we all understand (if perhaps not from a Serbian perspective). Mason seems to similarly be arguing that history is untrustworthy, but the argument feels a bit old-hat: even if we’re not textual scholars, we all know that the four Gospels, for example, tell stories that sometimes conflict. Maybe I’m jaded and this is inherently interesting in Mason’s book: but I would have liked it to lead somewhere beyond this. Maybe I’m reading this book for the wrong reason.

The footnotes of this book keep nagging me: they seem trapped between two forms, first, explaining the broader frame structure (along with a very brief preface, which assures us that these chapters are all lost books of the Odyssey), and second, providing basic background information on Homer’s poems for an audience that isn’t assumed to know anything. This is a bit problematic: the frame work is brief enough to not need to be there – the reader is quickly lost in the world of the Odyssey, not considering the archaeological pretense that would have been needed to bring these books to paper – and further mentions of the frame story unnecessarily jolt the reader out of that world. This might be good if it were more thorough; but the notes offer only a fragmentary history, not enough of one to maintain a suspension of disbelief. The ostensible audience also bothers: we are repeatedly told things that anyone with even a passing knowledge of the Odyssey should know; the assumption seems to be that the reader has not bother to read the original, but somehow wants to read the Lost Books, which might be better. This is strange, and I don’t really understand who this reader might be.

I’m circling around the content of this book, and that might not be fair. The 44 stories that make up this book are pleasant enough: Mason takes the characters of the Odyssey as readymades and moves them through his own plots or interpretations, using their voices as necessary. The plots might be conveniently described as Borgesian. This as well throws off the framework of the book: something that’s ostensibly been lost shouldn’t be sounding so much like Nabokov. Finding the postmodern in Homer is something: but is that enough to surprise anyone any more? Certainly this is a well-worn academic trick.

Perhaps I would have done better to track down a copy of the original Starcherone version of this book: I’m not sure what the differences are, but I suspect that Picador-supplied smoothness isn’t helping the book in my mind. As it is, I have a hard time liking it. It’s reasonably well done, and I think Mason is probably worth attention in the future; but I’m left wanting more.

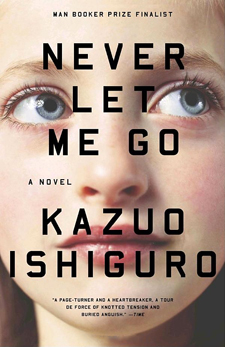

Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro