Pierre Souvestre & Marcel Allain

Pierre Souvestre & Marcel Allain

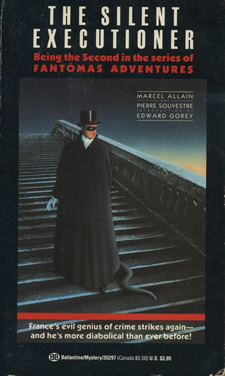

The Silent Executioner

(trans. unknown)

(Ballantine, 1987)

This is the second Fantômas book, originally titled Juve contre Fantômas: here in a cheap Ballantine paperback distinguished by an Edward Gorey introduction. It’s unclear who translated this edition from the French; the copyright page has a notice saying that “Revised translation © 1987 by William Morrow and Company, Inc.”; Gorey, in his introduction, also seems confused by this as well. Penguin reissued the first Fantômas book a few years ago with a John Ashbery introduction, which I liked well enough. Having just acquired the Louis Feuillade Fantômas series on DVD, I thought it was time to go back and read the other books, which can be found used for practically nothing. Maybe it would be nice to have a Fantômas collection, but I don’t know.

A great deal happens in this book. In its rough outlines, it’s similar to the Feuillade film; the action in the book, however, is considerably more labyrinthine. The book will not particularly illuminate the film (which, for the record, I saw before reading the book); the film, with its simplifications, might make the broad outlines of the book more comprehensible than they might otherwise be: this is tremendously episodic writing, the chapter being the operative unit.

The text of this volume isn’t quite as nice as the text of the first Fantômas, maybe because the language seems to have been updated for a mass-market audience of the 1980s. Nevertheless, one does occasionally find a sentence like this, after Fanômas and his cronies have wrecked a train for no appreciable reason:

Then cries of terror rose in the night as the frantic passengers fled from the luxurious train.

The “luxurious” makes this sentence for me; it could almost come from a Grand Guignol version of The Young Visiters, a fine thing to imagine. A few sentences later, still in the train wreckage, this passage presents a rare moment of humor:

The driver held out his two broken arms.

“Give me a hand, for God’s sake! (p. 70)

Maybe this captures the appeal of the book. When Fantômas kills a bunch of people with a train, seemingly capriciously, it isn’t understood by the reader as an immoral act; carrying out evil deeds is just what Fantômas does, and it doesn’t seem like he can help it. This isn’t quite a detective book, because Juve and Fandor will not capture Fantômas, at least not for long; their struggle with him is almost an ouroboros, because even if they stop him from carrying out some act of villainy, he will certainly strike again. (One wonders, offhandedly, whether the citizens of Paris might do better if Juve and Fandor were not trying to stop Fantômas and simply acceded to his rule. Every generation gets the Fantômas it deserves.) The pleasure of this book is at least in part in transgression: evil for its own sake. Since re-reading Proust, Lucretius’ reflection on the pleasure of watching the misfortunes of others has been on my mind: one enjoys a book like this because it is nice to see what terrible things Fantômas will get up to. Maybe this reflects poorly on us as moral beings; but it is a response that’s there, and it’s hard to get around it entirely.

This edition is lurid in the right way; the reader couldn’t discover from the book itself when exactly this was written (Wikipedia says 1911), a subterfuge which one suspects was perpetuated by the marketing people at Ballantine in the hope of attracting a mass audience. There is a brief “About the Author” (sic) at the end of the book, which notes that after Souvestre’s death Allain married his widow. The cover, unattributed, shows a masked man on a stairwell with what appears to be a rubbery tail coming out of the bottom of his cape; possibly he is holding a non-descript snake behind his back. (A snake, though not a non-descript one, does play a role in the plot; there is, however, no scene where Fantômas elegantly hauls around a snake.)

* * * * *

A self-referential interjection: for the past year, I’ve been working under the constraint that I need to write a non-trivial amount about every book that I read that isn’t being discussed in some other way, i.e. those things that I read for book groups or that I read for work. Categorizing these posts as “reviews” is misleading to a degree: what’s intended isn’t quite the same as a review, rather the need to respond. This is largely motivated by a need to re-examine why exactly it is that I’m reading what I’m reading; it’s also being done under the supposition that in the changing environment that the book finds itself, the role of the reader – specifically the reader who is more than just another consumer of a book – is one of growing importance. The flip side of this, of course, is the suspicion that not all reading is of the same value; and this ineluctably influences the books that I choose to pick up. I suspect that I would find myself reading more things like this book – light, not requiring much investment on the part of the reader – were I not concerned that I didn’t have as much to say on certain books. I can find something to say about this Fantômas book, for example, in part because I can talk more generally about the series as a whole; however, it would presumably be harder for me to find something substantial to say about a third volume in the series. I don’t know whether this is specifically good or bad; rather, it points out that the rules we live under, examined or not, do tend to dictate a particular form of reading. A book might be useful to a reader even if it doesn’t immediately have a use in the way that I’m defining use; maybe there are other criteria that I need to discern.